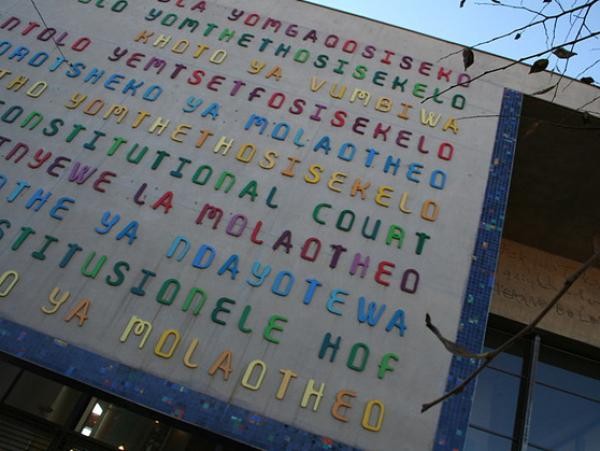

Withdrawal from International Criminal Court challenged in Concourt

CASAC argues the President has violated the separation of powers

The Council for the Advancement of the South African Constitution (CASAC), represented by Norton Rose Fulbright, has filed an application at the Constitutional Court challenging South Africa’s withdrawal from the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The application was filed against President Jacob Zuma, the South African government and a number of government officials including Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Maite Nkoana-Mashabane.

On 19 October, Nkoana-Mashabane signed an Instrument of Withdrawal which stated that South Africa had found its obligations for peaceful resolution of conflicts to be in conflict with its obligations under the Rome Statute, and as a consequence, was giving written notice to withdraw from the Rome Statute.

The terms of withdrawal are set out in Article 127 of the Rome Statute and the Implementation of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Act, 2002 (the Implementation Act): ‘A state party may, by written notification addressed to the Secretary General of the United Nations, withdraw from this Statute. The withdrawal shall take effect one year after the date of receipt of the notification.’

But CASAC argues the decision to withdraw is unlawful, irrational and in violation of the Constitution.

Firstly, Parliament can approve international agreements in terms of section 231(2) of the Constitution. However, section 231(2) only contemplates the approval of these agreements, not the withdrawal. CASAC contends that if Parliament is given the power to make international agreements binding, it also has the power to withdraw from them in the same way that Parliament has the authority to both pass and repeal legislation. However, this is not necessarily correct.

In terms of section 231(3) of the Constitution the President has the power to bind South Africa to agreements, which do not require ratification without the approval of Parliament. However, the Rome Statute was not such an agreement.

The Implementation Act expressly provides for written notification of South Africa’s withdrawal from the ICC, though it is not clear whether this provision is inconsistent with the Constitution.

It is also important to note that the Instrument of Withdrawal did not repeal the Implementation Act. If the Implementation Act is not repealed by Parliament, South Africa will still be bound to all its obligations under the Rome Statute under domestic law, despite a valid withdrawal under the statute itself. This is a situation which CASAC aptly deems ‘absurd and irrational’.

The real issue in this case concerns the separation of powers between the Executive and Parliament and the question of which organ of state has the power to withdraw from international agreements. The answer to this question is not that clear.

The power to bind South Africa to international agreements is divided between the two branches of government, with Parliament exercising a kind of ‘veto’. While the President has the power to sign international agreements, most are of no effect unless ratified by Parliament.

CASAC argues that the power to withdraw is vested solely with Parliament and that the President’s decision to withdraw is in conflict with his obligations under the Constitution to implement national legislation as well as the doctrine of separation of powers.

While there are no provisions in the Constitution dealing with withdrawal from international agreements, it is arguable that the President’s actions are in conflict with the spirit of his executive functions under the Constitution.

Furthermore, the Constitution’s silence on the issue is significant. The Constitution delegates specific powers to each branch of government and any exercise of power by government must be done in terms of an empowering provision. Where there is no empowering provision, the official or branch concerned lacks the necessary authority to exercise that power. This is a point CASAC argues briefly but convincingly.

It will now be up to the State to respond, though it is unclear what authority the Presidency will rely upon.

Despite all of the above, it is hard to see an outcome, which leaves the state with no ability to withdraw or exit from international agreements. This will be the Constitutional Court’s challenge come 22 November.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Walter Sisulu University reopens after two weeks

Previous: UCT staff protest against “militarisation” of campus

© 2016 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.