This is probably the list of artworks UCT has removed

University claims there are errors in our list that we obtained from a reliable source, but refuses to provide corrections

Following a long deliberation process, the Artworks Task Team (ATT) of the University of Cape Town (UCT) published a report in February that indicates the pieces of art removed and covered up in the past year will remain off the walls indefinitely.

The report appears to refer to a list of 75 pieces of works that were removed, the names of which GroundUp has received from a confidential source (list included at the bottom of this article) as well as 19 pieces of art determined to be controversial by student representatives on the ATT in 2015. The two lists, which most probably overlap with regards to certain pieces of art, in combination with the 23 works that were destroyed during the Shackville protests in February 2016, leave a gaping hole in UCT’s sizable collection of artwork as almost 100 pieces will be collecting dust in a storage closet for the foreseeable future.

In response to GroundUp’s request for confirmation of the below list of 75 removed works, UCT said that, “the list of the 75 artworks provided by GroundUp is not entirely correct.” However, the university has refused to reveal the titles of the works that are incorrect.

The ATT was started in September 2015 to advise the university’s Works of Art Committee on policy for statues, plaques, and artworks.

In response to criticism of the Task Team in the media, the ATT responded with a “clarification” of its role, distinguishing itself from the Works of Art Committee whom it said is “the body responsible for the development of policy for artworks.”

In the February 2017 report, the ATT published a list of “short- and medium- to long-term recommendations [that] were developed based on the outcomes of the audit of artworks, statues and plaques.” The first short term recommendation, to be implemented in one year, states:

“The University of Cape Town must keep artworks that were removed from the walls in storage pending a broader consultative process. This consultation may take the form of displays of some of the contested artworks, (in dedicated spaces such as the CAS Gallery), debates and discussions around specific artworks and/or themes. Seminars that may involve artists of ‘contested’ works may also be hosted by the WOAC and other departments in the university around different artworks and symbols.”

It is not clear if this “consultative process” has a time limit for how long the art will be kept in storage.

The report makes it apparent that some of the works were removed for safety reasons while others were removed for political reasons as “part of the transformation agenda” and calls on the Works of Art Committee to make clear the reason for removal.

“The Task Team [ATT] organised a joint meeting with the Works of Art Committee where it supported this initiative but advised that the motives for the removals should be made clear. For example, there needed to be public communication about whether the removals were only a measure for securing assets or if they were part of the transformation agenda. The lack of public communication by the Works of Art Committee incited widespread public speculation that removals amounted to censorship by the [ATT].”

One of the conclusions reached by the team discusses that although “there may not be a problem with individual artworks,” the overall effect of many works creates an unsafe, uncomfortable environment for certain people on campus.

“In our deliberations we found that while there may not be a problem with individual artworks, their cumulative effect, coupled with the lack of a considered curatorial policy, creates a negative feeling amongst some students and staff. We found that currently, UCT does not have a curatorial policy and would need to develop one that is transformation sensitive.”

Artists of the removed and covered works, including Diane Victor, Edward Tsumele, and Breyten Breytenbach, have publicly spoken out against UCT’s supposed transformation process, which the aforementioned artists regard as censorship.

In an interview with LitNet in April 2016, Tsumele said: “It is 100% a case of censorship, ironically in a democracy whose constitution allows for freedom of expression such as through art.”

When asked if South African art that is influenced from overseas trends can be viewed as a form of colonialism or neo- colonialism, Tsumele said, “Society should not attempt to dictate who should influence artists.” Further, “There should never be dictatorship with regard to how artists represent the human condition in their works; whether we agree or do not agree with such representation, it is none of our business as society.”

The report confirms the list of 19 works that were singled out by students on the team, though it does not name the pieces. In response to a query from GroundUp regarding the works, Elijah Moholola, Head Media Liason for UCT said, “[the works] were identified as part of the plan of the ATT to initiate discussions and debates around the contested artworks but such plans were affected by the protest action in February 2016.”

The ATT report states:

“The initial student representatives on the Task Team identified a list of 19 works in 2015 that were deemed to be controversial. Before recommendations could be made, however, the #FeesMustFall protests began, resulting in the closure of the University.”

It goes on to discuss the paintings that were destroyed during protests, without naming them:

“On 16 February 2016, twenty-three artworks were destroyed on Upper Campus during the Shackville Protests.”

A 2014 article criticising the over- representation of black bodies in negative and often degrading positions in artwork displayed across campus refers to a number of paintings and sculptures, including Willie Bester’s Saartjie Baartman and Diane Victor’s Pasiphae. Many of these were removed or covered up. These two artists are not on the list of 75 that GroundUp received, leading us to believe that the list of 75 is mostly separate from the 19 works. However, the reference to the “portrait of a naked white man, on his lap is a black woman” identifies Breytenbach’s Hovering Dog, which is, in fact, on the list of 75 artworks we received. This indicates that though UCT has said the 19 works identified were not removed because of protest disruption, works identified as part of the list of 19 may also be part of the 75 works that were indeed removed.

UCT has declined GroundUp’s request for the identification of the 75 pieces removed, for the identification of the 2015 list of 19 works discerned as “controversial,” and for the identification of the 23 pieces of art destroyed during the Shackville Protests.

In response to GroundUp’s question of whether or not the removal of these pieces of art goes against UCT’s ideals of freedom of expression, the university responded: “UCT continues to uphold freedom of expression as enshrined in the South African Constitution. The removal of the artworks is only a temporary measure while there is ongoing dialogue and debates over creating an institution that is inclusive and reflective of the diversity of the country.”

|

Table of artworks removed |

If you find errors in the list below, please alert GroundUp via [email protected]. |

|

|

Artist |

Title |

|

|

1 |

Justin Anschutz |

Split path |

|

2 |

Richard Keresemose Baholo |

Mandela receives honorary doctorate from UCT |

|

3 |

Richard Keresemose Baholo |

Stop the Killings |

|

4 |

Esmeralda Brettany |

Serialisation |

|

5 |

Breyten Breytenbach |

FG |

|

6 |

Breyten Breytenbach |

Hovering Dog |

|

7 |

Breyten Breytenbach |

SA Angel black/white |

|

8 |

Robert Broadley |

Flowers in a Vase |

|

9 |

Robert Broadley |

Portrait of an Old Man |

|

10 |

Robert Broadley |

Portrait of the artist, Nerine Desmond |

|

11 |

Robert Broadley |

Roses in a Jug |

|

12 |

Robert Broadley |

Roses in a Vase |

|

13 |

Robert Broadley |

Tree in Blossom |

|

14 |

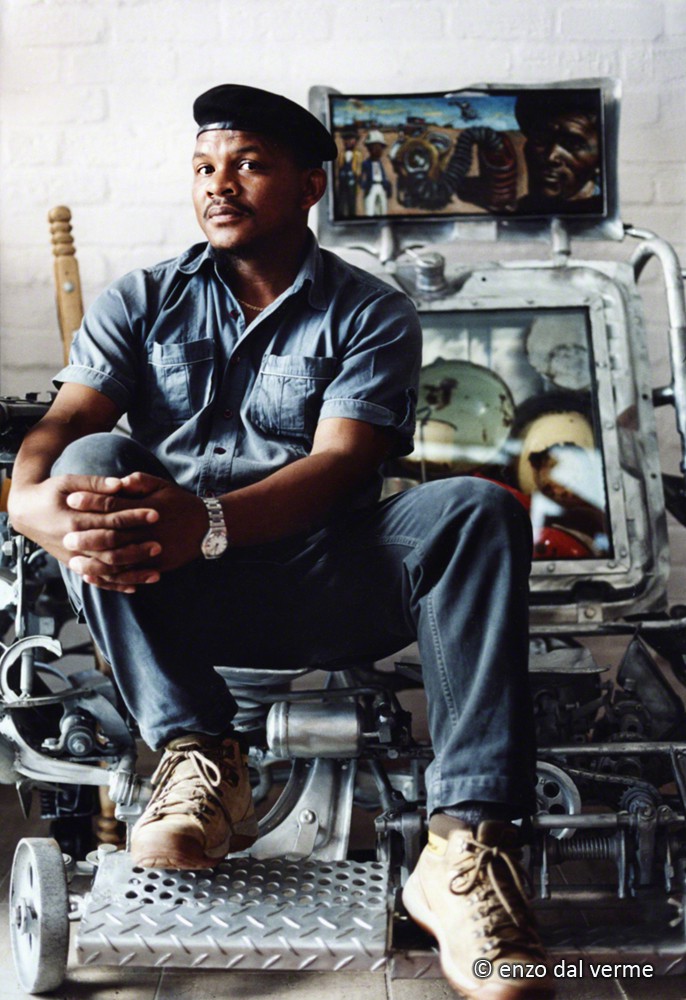

David Brown |

Travelling icon; an artist’s workshop |

|

15 |

Herbert Coetzee |

Portrait of Sir Richard Luyt |

|

16 |

Christo Coetzee |

Untitled (Ping pong balls) |

|

17 |

Steven Cohen |

Five Heads |

|

18 |

Philip Tennyson Cole |

Portrait of an unknown associate |

|

19 |

Mia Couvaras |

Untitled |

|

20 |

R Daniels |

Perversion |

|

21 |

R Daniels |

Pumpkin Aand |

|

22 |

R Daniels |

The Dreamer |

|

23 |

P de Katow |

Portrait of Prof James Cameron |

|

24 |

Lyndall Gente |

World in a Grain of Sand |

|

25 |

Constance Greaves |

Portrait of an African Smoking a Pipe |

|

26 |

Charles M Horsfall |

Portrait of Mrs Evelyn Jagger |

|

27 |

Pieter Hugo |

Dayaba Usman with monkey, Abuja, Nigeria |

|

28 |

Vusi Khumalo |

Township scene |

|

29 |

Isabella Kneymeyer |

A Quick Streamer Sketch, Fish River Canyon |

|

30 |

Isabella Kneymeyer |

Streamer Cross Hatch, Study Luderitz, Namibia |

|

31 |

Twinki Laubscher |

Reclining angel with cat |

|

32 |

Twinki Laubscher |

Seated angel |

|

33 |

Neville Lewis |

Portrait of JC Smuts |

|

34 |

James MacDonald |

Triptych 1 (The Apostles) |

|

35 |

Antonio Mancini |

La Prighiera |

|

36 |

Edward Mills |

Portrait of Alfred Beit |

|

37 |

W G Parker |

Portrait of Sir John Buchanan |

|

38 |

Henry Pegram |

Alfred Beit |

|

39 |

Michael Pettit |

Siegfried’s journey down the Rhine |

|

40 |

Joshua Reynolds (After) |

Duchess of Devonshire |

|

41 |

Joshua Reynolds (After) |

Lady Compton |

|

42 |

George Crossland Robinson |

Portrait of Prof Renicus D Nanta |

|

43 |

David Rossouw |

Sunningdale |

|

44 |

David Rossouw |

Welgevonden |

|

45 |

Edward Roworth |

Portrait of Dr Thomas Benjamin Davie |

|

46 |

Edward Roworth |

Portrait of Prof Theo le Roux |

|

47 |

Edward Roworth |

Portrait of Prof William Ritchie |

|

48 |

Rupert Shephard |

Portrait of JP Duminy |

|

49 |

Lucky Sibiya |

Village Life |

|

50 |

Pippa Skotnes |

The wind in //Kabbo’s sails |

|

51 |

Christopher Slack |

Twenty four hour service |

|

52 |

W T Smith |

Portrait of Henry Murray |

|

53 |

Irma Stern |

Ballerinas at Practice |

|

54 |

Irma Stern |

Portrait of a Ballerina |

|

55 |

Irma Stern |

Portrait of an African Man Blowing a Horn |

|

56 |

Mikhael Subotsky |

Untitled |

|

57 |

Mikhael Subotsky |

Voter X |

|

58 |

Hareward Hayes Tresidder |

Bowl of Flowers |

|

59 |

Andrew Tshabangu |

Bible and candle, Zola, Soweto |

|

60 |

Andrew Tshabangu |

Trance, Tzaneen |

|

61 |

Karina Turok |

Portrait of Mandela |

|

62 |

Unknown, Continental School |

Figure of a Standing Woman and a Study of an Arm |

|

63 |

Unknown |

Seated Woman and a Study of a Head in Profile and a Hand |

|

64 |

Hubert von Herkommer |

Sir Julius Charles Werhner |

|

65 |

Robert Heard Whale |

(Rev) J Russel |

|

66 |

John Wheatley |

Maidens at Play near Rock |

|

67 |

John Wheatley |

Portrait of Carl Frederick Kolbe |

|

68 |

John Wheatley |

Portrait of Dr E Barnard Fuller |

|

69 |

John Wheatley |

Portrait of JW Jagger |

|

70 |

John Wheatley |

Portrait of WF Fish |

|

71 |

Sue Williamson |

Aminia Cachalia |

|

72 |

Sue Williamson |

Cheryl Carolus |

|

73 |

Sue Williamson |

Helen Joseph |

|

74 |

Sue Williamson |

Mamphela Ramphele |

|

75 |

Michael Wyeth |

Blue Wall |

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Cape Town airport faces land claim

Previous: How you can help save the Karoo

Letters

Dear Editor

Art censorship (and let's not be coy about what the removal of certain "offensive" artwork really is) is but one step further down the dangerous, and slippery, slope of content control at UCT.

Other steps have been taken, or are in contemplation - "banning" of lecturers (Ken Hughes), abrogation of free speech (disinvitation of last year's TB Davie's invited lecturer), renaming or defiling so-called "colonial" statuary and buildings, and the restructuring of syllabi.

Might we look forward in the not too distant future to pre-authorization of lectures themselves?

It's very sad....

Dear Editor

In its statement in response to the withdrawal by David Golblatt of his photographs and other artwork from UCT (see: https://www.uct.ac.za/usr/press/2017/2017-02-24_Statement_GoldblattCollection_AM.pdf) the UCT Communication & Marketing Dept stated that UCT is guided by the Library and Information Association of South Africa (LIASA), and is committed to academic freedom. But LIASA's code states, inter alia, that "Members should ensure the free flow of information, freedom of speech and freedom of expression and the right of access to information." UCT has consistently failed to abide by this code, and has also consistently violated the principles of academic freedom, by, inter alia, censoring works of art by removing them or covering them up, by disinviting the 2016 TB Davie invited speaker, Mr Flemming Rose, and by failing to sanction those who actively infringe on the rights of others. That the UCT Executive can continue to claim the contrary adds insult to injury and seriously undermines UCT's standing as an institution of higher learning. Universities should actively promote and defend freedom of expression. UCT is not only failing in these duties but is at times actively undermining them. This is nothing short of disastrous - both for the future of higher education in SA, and indeed for democracy itself.

Dear Editor

What a prime example of the inherently South African expression of fascism! It is neither new nor original though: the late National Party already visited the same obscenities on us. Advancing under the banner of "righting injustices", "promoting Africanism", expectorating Western (sic) artefacts... we witness the condonation of classical fascist behaviour through the ages: doing away with anything that might challenge the closed and fearful mindsets of the mob.The world has seen this before in the book-burning orgies of the brave SA during the Nazi period (remember 'Entartige Kunst'?), in the courageous barbarism of China's Red Guards, in the ways the Pol Pot régime 'cleansed' Kampuchea, all the way through to the revolutionary ardour of Boko Haram. Welcome to the vomiting power of being human!

But why stop at such a piddling demonstration of effecting social and aesthetical justice?

I hereby declare my willingness to publicly put to the torch the three paintings that I had produced during the years of political blindness when I did not know what I was doing. I shall be naked, as behooves a penitent. I'm willing to grovel and kiss the smartphones of the revolutionaries. (I can't promise to flagelate myself, being somewhat of a coward.) The only favour I ask is that such a ceremony should take place in the presence of Dr. Max Price and his cohort of professors and other flunkeys.

Yours in abject contrition

Dear Editor

Emotive declarations of “pain”, “suffocation” and “outrage” are not sufficient justification to ‘ban’ anything, especially within an institution that, for decades, fought for and still claims to be free of the shackles of unchallenged ideology, discrimination, beliefs, myths and politics. If statues, artwork, building names, seminars, publications, courses, even people are to be side-lined, banned or removed, show legal cause for such actions or, at least, require interested, affected and ‘knowledgeable’ protagonists to argue their cases - for and against - in an open, heckle-defamation-free, transparent and widely publicized manner. In an institution like UCT that was once founded on striving for universal truth hindered by nothing that violates ”absolute intellectual integrity pursued in an atmosphere of academic freedom” (TB Davie), unilateral or narrowly ‘collective’ decision-making has no place.

During the last two years especially, the actions (epitomized be the treatment of artwork) and inactions of the UCT Executive have effectively suborned the violation of South Africa’s laws, internationally recognized human rights and personal freedoms in support of racially/nationalistically and/or ill-defined ideologies.

Dear Editor

Since the removal of the Rhodes statue, UCT management has taken the easiest way out of debate: close down, remove. Hopefully discussion will disappear, let’s duck intelligent argument. So much for a supposed institute of learning and academia.

If “transformation” is a process – and it should be, and positive – surely it should be enlightening, not a move to the dark.

The censorship of the university’s art, the pathetic way in which it is being taken into hiding, necessitates protest in the fiercest term – for the good of the future of UCT itself.

The banality and sophistry that “explains” the lists and process is an insult not only to the South African public, artists and the university itself.

And then there is the big question: what are the artists going to do?

Dear Editor

It strikes me that in order to fully appreciate what is going on at UCT it would be good to see the removal of certain pieces as a work in itself. This is performance art of which the active participants can be proud, but only when they realise what it is they have inadvertently done. Similarly UCT can be proud of its role in bringing about their enlightenment - when it finally happens. After all, what is a seat of higher learning if it does not facilitate active participation in the process of learning?

Mere sophistry, you say?

Sometimes when a child can't stop being destructive it's a good plan to join in and break a few windows yourself.

Too charitable a construction, you say?

Perhaps. But maybe when agency is trampled on long enough the only way for it to break free is to look at first as though it is wrestling with a few legs.

Dear Editor

The removal of art is a particular form of art that is conceived by an artist, placed in the public eye for viewing and carried out by a works of art committee.

© 2017 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.