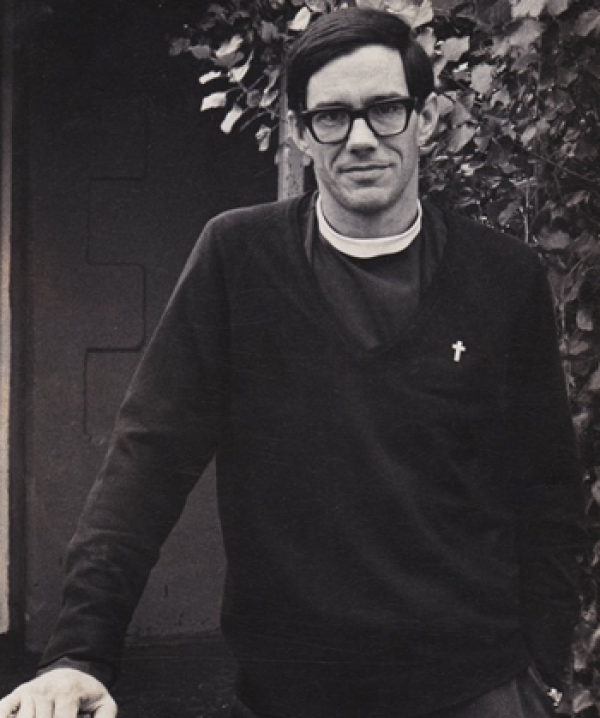

Obituary: Bishop David Russell

Bishop David Russell, who died last week aged 75, was deeply rooted in this land, participating fully in its trauma and its transformation.

He lived his life with profound integrity, challenging the Apartheid authorities in a unique and determined way, whilst providing shelter, protection, hope and courage to countless people. Seen in this perspective his death, whilst immensely sad, is not a tragedy but rather a moment to give thanks for an exceptional life.

David’s long ministry began typically enough in a remote area of the rural Ciskei, Qobo-Qobo (Keiskammahoek), where, without a natural flair for languages, he immersed himself for three years of painful, difficult and invisible work learning isiXhosa; an essential foundation for his work to come. He persevered until he not only spoke extremely good Xhosa but also had an armoury of powerful proverbs and sayings which he would bring out at appropriate moments to the astonished appreciation of both deep-rural and sophisticated-urban listeners whose mother-tongue he now sometimes articulated better than they did.

In 1970 he moved to King Williams Town. In his search for an effective ministry to the poorest and most powerless in the land, he chose to work as the parish priest amongst the people who were being moved into Dimbaza, a rough resettlement camp which had recently been established as the dumping ground for those an Apartheid Cabinet minister referred to as “surplus people”. These people were forcibly removed from farms and small towns in what was then defined as “White South Africa”. The law ceased to give them permission to remain there. As David described it: “It was like a shipwreck really. People who had been removed from some networks of economic survival to these places, were shattered. There was no work. People got sick and children were dying of malnutrition at an appalling rate.”

How to respond? With compassion, of course: feeding the hungry and clothing the naked was central to the gospel at the core of David’s being and he did that in full measure. But how to stop the barbaric process in an environment where virtually all political opposition had been crushed with most leaders either jailed or in exile with the racist Apartheid state at the height of its power?

Drawing on the thinking of men like Mahatma Gandhi who had developed his non-violent Satyagraha truth-force in South Africa two generations previously, David slowly began to devise a strategy for Dimbaza. He called it “putting your body on the line”.

He was not going to accept that the widows who had been uprooted and dumped were only getting a pension of R5 plus a meagre R2.58 for rations. He’d been inside their plank houses, hardly three metres squared, freezing in winter and baking in summer. After writing letters to Minister M.C. Botha, to no avail, he went to Cape Town to publicly fast on the steps of St. George’s Cathedral, in close proximity to Parliament. His posters read: HUNGER IS VIOLENCE and M.C. BOTHA COULD HELP. This publicity caused the Minister to offer a maintenance grant for each child of just below R3.00. Later, however, they were told that if they had a grant, the food rations would be taken away. This incensed David and, as he said: “What unfolded in my mind and conscience and heart was to live, myself, on the pension of R5 a month for six months, writing the Minister a monthly letter describing what this was like.” This he did. He “put his body on the line”.

It garnered publicity and was effective in shaming the government. Pensions were raised and, later, factories were built to provide employment at Dimbaza.

“Russell is the only man I know who has ever found a way to compel the System to respond to him,” Steve Biko once laughingly remarked soon after he, himself, had been banned to Ginsberg, his childhood township, on the edge of Kingwilliamstown. After his arrival, Biko very quickly sought out David Russell (David had, in fact, informed Mrs Biko, a staunch Anglican, of Biko’s banning order before he arrived). Almost immediately, David and his priest in charge, James Gawe, were able to provide church space next to David’s small house in Leopold Street, from which SASO and the Black Community Programmes operated; from which the Zanempilo Clinic emerged and Black Consciousness was further articulated.

Biko and David Russell, respectful of one another’s different strategies, became friends.

David was then 35. The second 35 years of his life were completely consistent with this ministry that he had pioneered so effectively. He moved to Cape Town to build a Ministry to Migrant Workers. He became deeply involved in the attempts to prevent the removal of the many informal settlements springing up around Cape Town in defiance of the migrant labour laws which prevented families from living together. Up until then, David firmly believed in celibacy but, whilst working in Crossroads, a beautiful Catholic nun crossed his path: Dorothea, kindred spirit and the love of his life. They married in 1980.

With Margaret Nash and a few other intrepid souls, David lay down in front of a bulldozer intent on destroying the self-built houses of families trying to survive in town. With even more courage he wrote a scathing pamphlet detailing the way in which the security forces were encouraging and arming the notorious Witdoeke to cause mayhem in the townships, activities that were a precursor to the Third Force destruction later, during the early 1990s. The State was not amused. David was charged and then, in October 1977, together with other troublemakers such as Beyers Naude and Theo Kotze of the Christian Institute, he was banned for five years.

Subsequently David and Dorothea moved back to the Eastern Cape with their two sons, Matthew and Andrew. There he worked for many years, first as the Suffragan Bishop of St. Johns in the Transkei and then as Bishop of Grahamstown. His ministry focused, as always, on those who are most vulnerable in society. He continued to challenge those in authority, including the new democratic government, to do what they should be doing. When he retired to Cape Town he found his work amongst possibly the most vulnerable and marginalised of all groups in our society today: gay, black women who are living in the urban townships. Practical support combined with hard-headed theological understanding and defence of their position was what he provided until his illness prevented it.

Some idea of what David Russell’s life meant to those amongst whom he worked is evident in the presentation made by the Holy Trinity Church in Dimbaza in 2007, almost 40 years after he worked there: It reads, “A compassionate, visionary leader and anti-Apartheid activist.”

A few days before he died, before he had moved home, I asked David if, in that hospital ward, he could sense the presence of God. His immediate reply, firm and convinced was direct: “I have a deep trust.” That unshakeable trust in God infused his whole life and work. Not without his acknowledgement of his own human failings, it made him the compassionate, courageous person of prayer and action that he was. Humble to a fault, he was, undoubtedly, a great man.

Francis Wilson is emeritus professor of economics at the University of Cape Town. This is an edited version of the address delivered on his behalf by Lindy Wilson at Bishop David Russell’s funeral service at St George’s Cathedral on Saturday.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Meet female soccer ref Insaaf Baatjies

Previous: The battle for Rolihlahla Park

Letters

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.