How we count our dead during Covid-19

From 6 May to 23 June, at least 4,000 South Africans died because of the pandemic

Transmission electron micrograph of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles, isolated from a patient. Image captured and colour-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID (CC BY 2.0)

Every day the Minister of Health makes public how many people have died of Covid-19. The numbers are: 48 last Friday, 73 on Saturday, 43 on Sunday, 73 on Monday, 128 on Tuesday, our highest number in one day so far, and 92 on Wednesday.

The daily deaths appear somewhat random, but it is clear when you look at them over months that they are rising.

Those numbers are used to update dashboards on websites many of us have become familiar with during the pandemic, such as Worldometer, Bing and Media Hack.

Each province’s health department is responsible for counting its deaths and then feeding these to the National Department of Health.

Andrew Boulle is a public health specialist with the Western Cape Health Department. He has for many years helped develop the province’s health data systems, which are probably the best in the country (though Boulle is far too modest to admit this).

Boulle explains that the total number of Covid-19 deaths in the province are calculated from three sources:

- All patients admitted to the public sector system are tracked until discharge or death, and are identified as being potentially Covid-19 patients through the results of their Covid-19 tests.

- The Health Department receives data from private hospitals, who notify the department directly of deaths of patients with Covid-19.

- The Department is also notified about deaths of people in communities with suspected or confirmed Covid-19 cases. However, many of these deaths are expected to go unreported.

“We suspect therefore that the trends in reported deaths due to Covid-19 in the Western Cape are reasonably reliable, and certainly comparable to reporting in many countries, even if there is consistent under-reporting, particularly of out-of-facility deaths,” Boulle says.

As with all countries, this should be seen as the minimum number of daily Covid-19 related deaths. There are many reasons why a death due to Covid-19 may not make its way into the provincial, and then national, statistics. For example, some people will die of the disease without ever getting tested or diagnosed. Some die at home or in institutions.

This is not a shortcoming of data peculiar to South Africa; even countries with highly sophisticated systems face this problem. Analyses by the Financial Times, New York Times and Washington Post show that the United States, Italy, Spain, France, United Kingdom, Belgium and many other countries are underestimating their Covid-19 deaths.

And those are the countries with good enough data systems to know this. For many countries in the world, the epidemic’s death toll will never be more than a rough guess. So when you read on the Worldometer dashboard that there are currently 516,000 deaths, you need to realise this is far below the real death toll.

How do we know this? Well, countries that have good historical death data and good death registrations systems can compare how many deaths are occurring now with previous years. And South Africa is fortunate to be such a country; we have a pretty good death registration system.

A team at the Medical Research Council led by Debbie Bradshaw has been counting these deaths and publishing weekly reports. Until the latest report, South Africa appeared to be doing well; deaths were below the expected historical average. This was because of a massive drop in homicides and vehicle collisions during the lockdown.

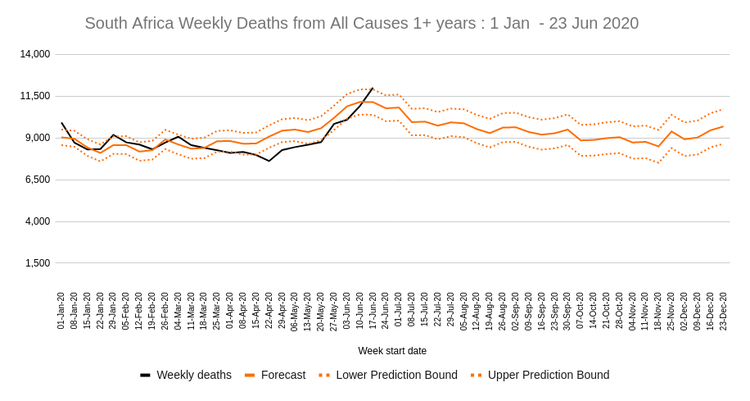

But the latest report, which came out on Tuesday and provides data until 23 June, is grim. For the week ending 23 June, South Africa had more deaths than we’d expect at this time of the year. This is shown in the graph below. Previous reports showed excess deaths were only occurring in the Western Cape and Eastern Cape, but now it’s happening in most provinces.

The latest Medical Research Council report on weekly deaths shows that for the week ending 23 June there were excess deaths in South Africa. This can only be explained by the Covid-19 pandemic, though some of the deaths may have been because people could not access the usual level of health care. Source: MRC

The number of excess deaths for 6 May to 23 June per province is in the table below, as well as the official number of Covid-19 deaths as of 30 June (we’ve used the official number from a week later to allow for the time lag in capturing results, although this introduces another problem: it includes at least some deaths from after 23 June).

| Province | MRC Excess deaths 6 May-23 June |

DOH Covid-19 deaths Up till 30 June |

| Eastern Cape | 1,421 | 422 |

| Free State | 69 | 9 |

| Gauteng | 399 | 216 |

| Kwazulu-Natal | 351 | 126 |

| Limpopo | 95 | 10 |

| Mpumalanga | - | 7 |

| North West | - | 7 |

| Northern Cape | - | 1 |

| Western Cape | 2,366 | 1,859 |

| TOTAL | 4,039 | 2,657 |

This table shows the excess deaths calculated by the MRC versus the official Covid-19 deaths calculated by the Department of Health. We used 30 June for the health department’s statistics to allow for lag in capturing results (although it introduces the problem that in the right column are certainly some deaths from after 23 June). Not all excess deaths are likely to be directly from Covid-19, but they can be said to be caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Note how the excess deaths far exceed the Covid-19 deaths. Now, it’s true that not all the excess deaths are from Covid-19. In some, perhaps many, cases, people without Covid-19 may have died because they didn’t get the medical help they needed, perhaps because of the pressure hospitals are under or because they didn’t seek help timeously out of fear of contracting Covid-19 at a hospital. But nevertheless, almost are all are people who have died because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The MRC data also has limitations. Death registration is done by Home Affairs officials. The MRC report points out that some Home Affairs offices have closed temporarily because of Covid-19 outbreaks, and this has resulted in delays in capturing the data.

Also as the report says, there is no universal understanding or definition of the term “excess deaths” (though all countries use registered death data to estimate excess deaths). In South Africa, only people with ID numbers are captured. People who don’t have ID numbers and foreign nationals are not included in Home Affairs death data. But by far the biggest source of undercounting is deaths that are not registered because Home Affairs is never notified of them. In the latest MRC report, Bradshaw and her team have tried to account for all this.

Finally, some of the provinces are still reporting very few Covid-19 deaths. The death rate of confirmed Covid-19 cases in the Western Cape as of Wednesday is the highest at about 3%. A trend across many regions is that the death rate rises as the epidemic grows; there is a lag between the initial infections and the first deaths. Yet North West’s death rate is a rather implausible 0.15%.

When asked about Gauteng’s low mortality rate (currently at 0.5%), Kwara Kekana, spokesperson for the MEC of Health, told GroundUp: “All hospitals are legally mandated to report all deaths as soon as they are compared. There is a reporting process through district coordinators.”

Kekana said that these reports are analysed daily before being submitted to the National Health Department.

“There are no identified data collection issues that may significantly affect the stats,” said Kekana.

But at least some deaths at institutions, undiagnosed Covid-19 cases and deaths at home would probably not be included in the Gauteng (or any province’s) stats.

(We attempted to speak to all provincial health departments for this report, but Kekana, Boulle and Bradshaw were the only people who provided us with useful information.)

Many people find statistics like these cold and heartless. But statistics contribute to society’s collective memory of this disaster. Included in those statistics are AIDS activist Nomandla Yako, former head of UCT’s computer science department Ken Macgregor, MRC scientist Gita Ramjee and nurse Anncha Kepkey.

The epidemic is escalating fast in South Africa, and the statistics in months to come will confirm the illness and death many of us confront.

CORRECTION: Apologies for misspelling Kwara Kekana’s name in an earlier version of this article.

Also, we made small improvements to the article after feedback from the MRC researchers.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Covid-19: SADTU members quit schools to mourn dead colleagues

Previous: “We are forgotten. We will be remembered when the elections are closer”

© 2020 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.