How an arms company tried to block your right to know - and failed

Integrated Convoy Protection misled the court

The Western Cape High Court eventually ruled against an arms company after it brought an urgent application against Open Secrets. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

A recent investigation by Open Secrets into South Africa’s role in the murky international arms trade was gagged by the Western Cape High Court at the insistence of a private arms company. The gag has now been lifted by the same court, which has affirmed the public’s right to know. This underscores the importance of evidence-based reporting on the activities of corporations who sell equipment and weapons systems that may be used to harm civilians far from the shores of South Africa. It is also a reminder that companies like these can mislead the court, requiring vigilance from civil society.

On 27 November, the Western Cape High Court dismissed the urgent interdict application brought by Integrated Convoy Protection (ICP) against Open Secrets, with costs. This followed from the holding order which operated as a prior restraint interdict or ‘gag order’ granted by Acting Judge Cooper on 5 November 2025, which barred Open Secrets from disclosing any facts related to the contents of the order including the very order itself.

In the period between the granting of the ‘gag order’ and the date of the hearing (where the urgent interdict application was dismissed), numerous civil society organisations expressed alarm at the unprecedented scope of Acting Judge Cooper’s order. How could it be that a matter of significant public importance could be rendered unreportable? Worse, how could it be that the very party that had sought the order in the first place could be granted a cloak of anonymity by a court of law?

The facts relating to how the order was given cannot be separated from how the order and the attendant relief was sought. At the hearing, Open Secrets argued that the wide reaching implications of Acting Judge Cooper’s order were in effect the result of ICP’s abuse of process and ‘unclean hands’. In other words, that ICP sought favourable relief from the court by deliberately misleading the court in both process and in substance. In such instances, it was only appropriate for a court to dismiss the application with costs.

Timeline of Application

On the morning of the hearing, Judge Nathan Erasmus went over the timeline of how the application was brought. The timeline shows how ICP’s case was unfair.

On 5 November, ICP approached the court, claiming extreme urgency. ICP served its application on Open Secrets at roughly 12pm, giving us 30 minutes to give notice of intention to oppose and further requiring Open Secrets to file an answering affidavit by 2pm. The matter was heard 15 minutes later, at 2:15pm.

Given the fact that Open Secrets would have to confer with our legal representation, read ICP’s founding papers (92 pages in total) and travel to court within that same period, Judge Erasmus indicated that Open Secrets’ allegation that the application was effectively ex parte (taking into account the interests of only one side) was merited.

ICP could very well have brought the application urgently at the end of the day or the following day without prejudicing itself or Open Secrets. Instead the company brought the case in a manner which did not give Open Secrets a fair opportunity to respond.

Our courts have previously set out the procedures for bringing a matter on extreme urgency, all of which safeguard against the usurpation of the audi alteram partem (to listen to the other side) principle. ICP’s resort to ‘ambush litigation’ not only prejudiced Open Secrets but the court too.

Unclean Hands

It was not enough for ICP to mislead the court procedurally. It also distorted the material facts of the matter. ICP approached the court with ‘unclean hands’, that is it “sought to use the legal process for an ulterior purpose or by recourse to conduct that subverts fundamental values of the rule of law”. Our courts have been categorical in their condemnation of this type of litigation, denouncing it as abuse of process.

In its founding affidavit, ICP claimed that it did not supply ground vehicles to International Golden Group (IGG) but ‘off-the-shelf’ commercial parts. The IGG is a United Arab Emirates-based arms company owned by Edge group, a state-owned Emirati arms conglomerate.

To support this submission, ICP provided the court with a heavily redacted contract between itself and IGG. All references to the word “vehicle” were edited out (no less than 76 times) including the title of the contract itself, which states:

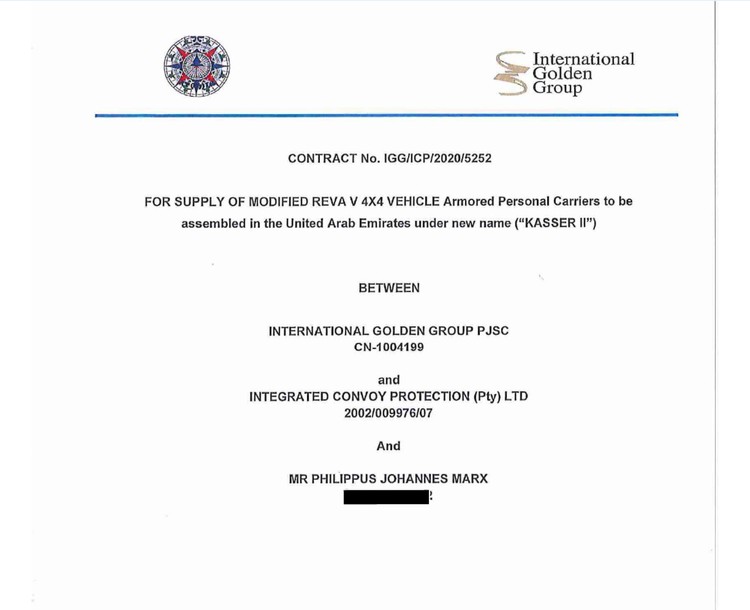

“FOR SUPPLY OF MODIFIED REVA V 4X4 VEHICLE Armored Personal [sic] Carriers to be assembled in the United Arab Emirates under new name (“KASSER II”)”

This is the redacted version of the first page of the contract between ICP and IGG that was submitted to the court.

This is the unredacted document except for an ID number we have removed.

ICP used those redactions and that argument as a basis for its claim that the allegations intended to be published by Open Secrets – namely that ICP was at best mislabelling its products to avoid South Africa’s extensive regulatory requirements for the cross-border trade in arms, i.e. that commercial parts did not constitute vehicles and were thus not subject to permitting requirements – were not in the public interest and therefore could be kept confidential through a restraint on publication.

The unredacted copy of the contract was not made available to Acting Judge Cooper who only had sight of the redacted contract. ICP did not respond to Open Secrets’ allegations that the redactions of the word “vehicle” were precisely to conceal the fact that the contract was not simply for ‘off the shelf’ commercial parts. Put differently, the problem is not that ICP provided the court with a redacted version of the contract between itself and IGG, but that this version was effectively doctored to support the unjustifiably broad relief it sought. Had the acting judge been provided with a version of the contract that did not conceal the true nature of the contract, the relief sought after by ICP would likely not have been granted.

In other words, and as Open Secrets has always claimed, a contract for the sale of military vehicles to a foreign sovereign, which escapes regulatory scrutiny, is well within the public interest and should therefore be made public.

War is a matter of public interest

The UAE currently supplies arms to parties to an ongoing armed conflict in Sudan where war crimes and human rights violations are being widely reported. International experts have raised the imminent risk of a genocide taking place too. That a South African arms company may be implicated in the wide-reaching nexus of unlawfulness between the UAE and the mounting killing in Sudan is a matter of significant public importance. ICP was well aware of this and presented itself to the court as a party to an otherwise innocent and purely commercial contract. (We are not aware at this point if ICP’s vehicles have ended up in Sudan.)

ICP has gone to great lengths to deceive the public of the origin of its weapons of war. It seems to have grossly overestimated its ability to continue doing so before South Africa’s courts of law.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

© 2025 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.