Ecological disaster in the Hemel-en-Aarde Valley

The collapse of a precious palmiet peatland exposes failures and tensions in the management of our water resources

In September 2023 the Onrus Peatland in the Hemel-en-Aarde Valley washed down river into the the popular Onrus estuary, destroying it. Photos: Sean Christie

The silt has yet to settle in the Overberg after an ancient and extremely rare palmiet peatland washed out of the Hemel-en-Aarde Valley in September 2023, destroying the popular Onrus estuary and depositing millions of tonnes of mud on the private golf course and mansion lawns of billionaire Johann Rupert. Was it a natural or man-made disaster, and if the latter, who should be held accountable? Sean Christie investigated.

The renowned Hemel-en-Aarde valley in the Overberg has seen better days. Hillsides that look green from a distance harbour thirsty invasive plants – rooikrans, black wattle, Port Jackson and eucalyptus – while a river named for its wildness, the Onrust (later shortened to Onrus), is little more than a trickle much of the year round.

In the lower part, a series of raw canyons have spread across the valley floor. You don’t need to be an astute reader of landscape to see that something bad has happened here, and that water is implicated.

The flood

On 24 September 2023, the Western Cape experienced what meteorologists call a Cut-Off Low (COL): a slow-moving, low-pressure system spun out of the mid-latitudes south of the continent. COLs drop significant volumes of rain, and the September 2023 COL was a monster, dropping 300mm over parts of the province in a 48-hour period. Roads washed away, homes were flooded, and throughout the Cape Fold Mountains there were thousands of landslides.

The Hemel-en-Aarde Valley received 135mm, sending a dark tide of mud and water into the Onrus estuary. It wasn’t long before the beach broke open and the flood rushed through, turning the ocean black for several days. Near-shore fishermen observed a mass exodus of West Coast Rock Lobster and a die-off of molluscs, including endangered abalone. The riverbed was raised up by two metres. The estuary – the town’s main tourist attraction – was transformed into a messy dune.

Millions of tonnes of silt and peat were deposited on the private golf course and mansion lawns of billionaire Johann Rupert, whose family has since been involved in efforts to dredge the Onrus Estuary.

The dark clodes of peat rolling in the floodwaters could only have come from the large palmiet peatland in the valley. Peatlands don’t easily wash away; there were other factors at play.

Videos from September 2023 supplied by Anton Kruger

The peatland

What remains of the peatland is obscured by a barrier of reeds. A network of deep ravines fan out from it, littered with blocks of peat, some with slowly desiccating plants still in them.

According to wetlands expert Kate Snaddon, the Onrus River has its source in Babilonstoren mountain, 16 kilometres away. Ages ago, at its lower end where the valley is pinched by coastal hills, a blockage must have formed, causing a wetland filled with palmiet – prionium serratum.

Wetlands and riverbanks in the Western Cape are the choice environment of Prionium serratum, commonly known as palmiet. Both the scientific and common name are strong aids to visualization: Prionium is Greek for sawblade, while serratum means toothed in Latin. The word “Palmiet” is derived from wilde palmit, the name the first Dutch settlers pinned on the plant, because it reminded them of the Mediterranean fan palm, or palmito.

“When palmiet dies and decomposes, peat is formed, but it happens very slowly, at a rate of about a millimeter a year,” says Snaddon.

Over time, more than 30 hectares became covered with peat, running to a depth of nearly eight metres.

“At these dimensions a healthy peatland is a vast carbon sink, which also functions like a giant sponge and filtration unit rolled into one, ensuring a steady year-round flow of clean water downstream,” said Snaddon.

But “in the last 100 years or so, roads have been cut through and around it, causing the lower part to gradually crumble away. Invasive plants have been allowed to encroach, and the valley’s rivers and streams have been impounded or restricted, progressively depleting its base flows.”

“It has been hammered from both ends,” says Snaddon. “And then in 2019, it caught fire.”

The fire

On 9 January 2019, a fire to burn refuse on Camphill Farm in the valley broke loose and rapidly spread to several neighbouring farms. After the blaze was contained, an area bordering Camphill and Hamilton Russell Vineyards continued to smoke, confusing firefighters who turned their hoses on it for days to no effect.

“It was the peatland, which had become totally desiccated, burning at depths the firefighters couldn’t touch,” explains winemaker Anthony Hamilton Russell.

The destroyed Onrus Peatland, at the foot of Hamilton Russell Vineyards.

He proposed that a wall of sandbags be built at the lower end, and that water be released from De Bos dam upstream to soak the area. This was also recommended by the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS), but the municipality, which depends on the dam for almost all of its raw water, rejected the idea, fearing, in the words of current municipal manager Dean O’Neill, it “would have posed a serious risk in terms of the community’s basic human needs”.

The Overberg municipality’s environmental unit recommended spearing the smouldering peat with perforated metal poles attached to hosepipes, a contraption known as a spike branch.

The subterranean fire was eventually doused but it took nine months and the peatland had now started to erode. The municipality turned to experts at Working for Wetlands. Snaddon, who was part of that team, recalls fierce debates about how best to intervene.

“One person wanted to dump dolosses in the peatland to prevent further erosion. Another offered to don his wetsuit and pack sandbags at the base of the head cut. All of these pretty wild ideas were being thrown around, some of which may actually have worked, but the Department of Environment, which has strict rules about intervening in rivers, kept on saying no, and all the while the peatland was eroding,” she says.

The rehabilitation interventions Snaddon and her team came up with were ultimately approved, but by then the covid pandemic had struck and the country was in lockdown.

“For the next couple of years there was no action at all, and then the big storm hit.”

The first rains after the fire washed away the ash from the burnt peat, causing runnels in the peatland. A ledge formed at the bottom end, known as a head-cut, over which water tumbled with enough force to undermine the base and bring peat tumbling down again and again. In the two years since the storm, the head-cut has moved 1,500 metres up the valley, releasing more than six-million cubic metres of peat and silt downstream.

The head-cut in the Onrus peatland has progressed by a kilometre and a half in two years, releasing a quantity of of peat and silt downstream that would fill 2.400 olympic swimming pools.

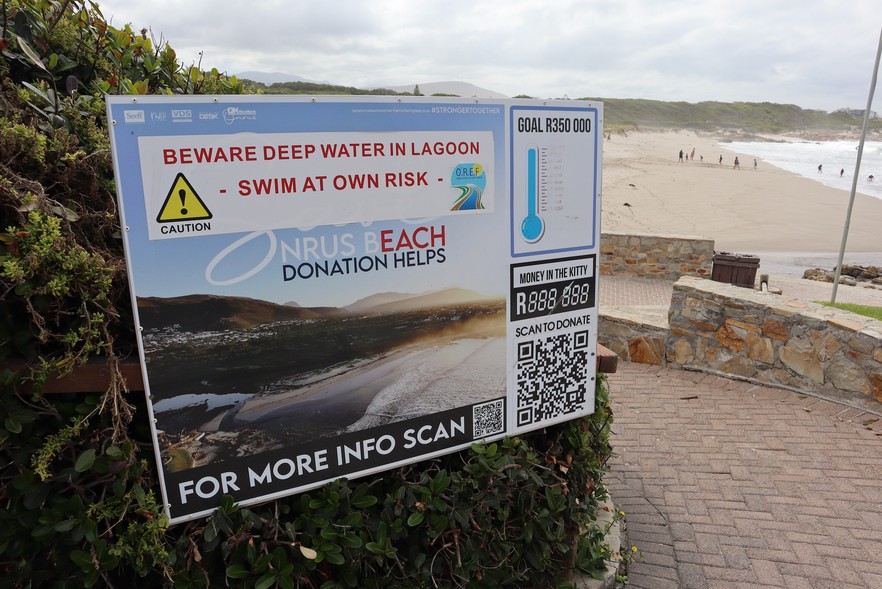

The Onrus estuary - the town’s main tourist attraction - is no more

The estuary

The man who wanted to jump into the river in his wetsuit was Anton Kruger, a kite surfing instructor in Onrus. He lives in a home notable for the number of cars and boats being worked on out front. In a living room that also functions as an office, workshop and sleeping area two sweet boys were making Plaster of Paris sculptures drawn from a book of caricatures. Kruger’s partner made mugs of rooibos and talked about a recent mid-equinox celebration in the hills.

“As kids we used to draw salt prawns and pencil bait from the estuary shallows. You can’t do any of that now,” he says.

We walked together to the estuary along quiet roads. I remembered it well from a visit a few years before: the tiered, grassy embankment above the main channel, and the Waffle Shack on stilts at the estuary’s edge. The difference now was the absence of water, which had been over two metres deep.

Kite-surfing instructor and fisherman Anton Kruger has been raising the alarm over water quality issues in the Onrus estuary since 2002.

“In South Africa, water resources are assigned an alphabetical category from A to F to indicate their ecological wellbeing and importance, with A indicating a state closest to natural and F indicating a critically modified condition. Since the flood, Onrus estuary has been downgraded to a category F resource, which basically means it no longer functions as an estuary,” says Kruger.

We crossed to its eastern edge and proceeded upstream, Kruger picking and eating red skilpadbessies along the way. In the early 2000s, he had noticed changes in water quality, linked to sewage spills. Concerned, he joined the Onrus Estuary Forum, and through regular testing found that levels of e-coli in the lagoon were dangerously high at times.

“The other part of it was the amount of water entering the estuary, which a lot of the time was barely a trickle,” he says. But nobody seemed interested in looking into the issue of inflows, and so Kruger did.

“What I found has opened a real can of worms,” he says.

We rounded a small dune and the river came into view, sliding over a swathe of chalky grey soil that had been cross-hatched by the tracks of gigantic amphibious excavators. Two of these were parked under trees at the foot of the long, sloping lawn that sweeps up to the pillars of a mansion owned by Johann Rupert.

“When the flood came down in 2023 it dumped silt on Rupert’s property, including his private nine-hole golf course,” says Kruger.

Before the floods the Onrus estuary was up to two metres deep in places

The Rupert family has been very involved since in efforts to dredge the estuary.

“Millions of tonnes of silt were shifted but all of that work was undone by another massive storm in July 2024,” says Kruger, and, as if on cue, he sank up to his hips in the silted river channel.

Siltation has turned the bed of the Onrus River into quicksand

Des Bos Dam started supplying water to the communities along the Whale Coast in 1976. The amount of water that can be taken from it was set down in a 1973 order of the Water Court, but the Overstrand Municipality has routinely over-extracted water for decades.

The dam

De Bos Dam supplies Hermanus, Onrus, Zwelihle, Sandbaai, Vermont, Fisherhaven and Hawston. From its wall, one sees a shoreline fringed with pink Erica and red Tritoniopsis, with dark waters lapping against the green valley slopes.

“The dam used to spill every winter, keeping the peatland saturated, but the municipality started taking more and more water, and the dam stopped spilling, causing the peatland to dry out,” explains Kruger.

Russell confirmed that the peatland, which lies at the foot of his vineyard, “used to flood in the 80s, but hasn’t for years”.

“Our records show that the average annual rainfall has actually increased. Quite simply, the municipality became greedy,” he says.

When the dam was proposed by the town of Hermanus in the late 1960s, it outraged farmers and residents of neighbouring Onrus and Vermont, who depended on the river’s water.

The dispute went to the Water Court (a judicial body replaced by water tribunals after 1998), which in 1973 handed down operating rules aimed at ensuring the existing users of the river would continue to receive a share of the water.

An annual dam abstraction limit of 2.8-million cubic metres was set for the municipality. (The dam’s full storage capacity is 5.8-million cubic metres). The court ordered that downstream farmers must continue to receive water, based on an average of seasonal inflows. The needs of the ecosystem did not feature at all, although the environment indirectly benefited from the water that was released for farmers.

The dam was expected to meet the water demands of Hermanus, Onrus and Vermont until the year 2000, when additional capacity would be required. But South Africa would transition to democracy, and the Overstrand Local Municipality would absorb most of the urban and rural settlements in the Greater Hermanus area, rapidly increasing the number of people who depended on De Bos Dam. And yet, the operating rules from 1973 still applied.

In response, the municipality decided to develop boreholes. But according to its infrastructure and planning department, these under-delivered due to a range of issues, including electricity outages and theft. Meanwhile, the population of Greater Hermanus has more than doubled since the early 2000s.

After some digging, Kruger discovered that in the three years before the 2019 peatland fire, in order to spare ratepayers from extreme water restrictions during the “Day Zero” drought, the municipality took a third more water from the dam than its allocation in both 2015 and 2016, and half a million cubic metres more in 2018. The municipality also released significantly less water downstream than it should.

GroundUp earlier this year reported that Overstrand Municipality has exceeded its water allocation limit more than 80% of the time since 2003, yet simultaneously received top marks for water management from the water department.

The outlet pipe below the wall of De Bos Dam is a mere 106mm. “The whole of the Onrus River has to go through that,” says Anton Kruger, who in 2025 laid criminal charges of water theft against various people at Overstrand Municipality.

The aperture of the pipe through which the municipality abstracts water is 400mm, three times the diameter of the pipe through which water is released downstream into the Onrus River. Until 1998, South Africa’s water policy did not consider the needs of the environment.

“We have two ecological corpses in the Hemel-en-Aarde Valley – the peatland and the estuary – both downstream of a dam the municipality operates like its own personal faucet. It’s the most basic form of ecological cause and effect, a child could understand it,” says Kruger.

He says he repeatedly approached the municipality with his findings, and was told that the disasters had resulted from an unforeseeable combination of drought, fire and flood.

When the municipality stopped talking to him, he petitioned the DWS right up to the level of director-general. An investigation was launched.

Muddy waters

On 28 November 2024, a meeting was held at the head office of Whale Coast Conservation, called by the Breede-Olifants Catchment Management Agency (BOCMA) in response to accumulating questions about the ecological mess.

BOCMA and the country’s five other catchment management agencies (CMA) are the creation of the National Water Act of 1998, which replaced the 1956 Act. Their mandate is to ensure that water resources are managed in sustainable and equitable ways.

In a room covered with environmental posters – “Eye on pangolin”, “It’s a frog” – the mood was comedically tetchy. “Where’s my ballpoint pen gone,” one attendee insistently repeated. “What’s this stompstert cat doing in here,” another cried. The municipality’s withdrawal from the meeting at the last minute did nothing to improve the mood.

BOCMA’s Fabion Smith told the meeting “that a complaint of over-extraction has been laid against the municipality, and we are investigating.”

Although Smith did not divulge it then, the BOCMA team had already received data showing that the municipality had over-extracted more than 80% percent of the time since 1996.

BOCMA, at the urging of the DWS head office, directed Overstrand Municipality to stop over-extracting and to regularly report its abstraction data to the department.

The other thing Smith knew but did not say is that the municipality would not be held to account for its historical over-extraction. Had this information been shared it would almost certainly have caused an uproar, but as another of the speakers emphasised - environmental consultant Barry Clark - the issue of water reallocation is not straightforward.

“Where the 1956 act gave scant regard to the environment, the 1998 act made the environment a priority user. Its share is referred to as the ecological reserve, which CMAs such as BOCMA must progressively implement,” he explains.

In 2018, DWS conducted a classification study of water resources in the area, and from this worked out an ecological reserve for thousands of segments of dozens of rivers. The “reserve” approved for the Onrus River is 19% of the catchment’s mean annual run-off, which according to Clark would require the municipality to release approximately 0.7 million cubic metres from De Bos Dam annually.

“It seems low,” he says, adding that the data for the Onrus River “was simply extrapolated from a neighbouring catchment”.

Yet implementing even this meagre ecological reserve has proved problematic. BOCMA’s Smith explains that the dam was not designed to be able release more water than directed by the Water Court in 1973.

“The reality is that water is required for food production, and for domestic and industrial use, whilst the ecosystem also requires water. The challenge we have is to balance the demands on supply, and this will have to be done through a process of open consultation between all who use the water,” he says.

In the parking lot, a disappointed Kruger summarised the situation from his perspective.

“It has been 27 years since the new Water Act was passed, and South Africa’s water authorities still haven’t figured out how to give the environment the water it needs. Meanwhile, all of these irreplaceable water resources are being lost. What are we going to tell our children?”

Despite being given ample time the municipality had not responded to our questions by the time of publication. But for a previous story, the municipality told us that before the 2019 fire it was not aware that there was an important peatland below De Bos dam, and was never informed of a specific volume of water that needed to be released to sustain the peatland.

Postscript

Following the environmental disasters in the Hemel-en-Aarde Valley, the Overstrand Municipality launched a project “to restore and rehabilitate the entire Onrus Catchment, particularly the Onrus Peat Wetland, due to extensive degradation over the years”.

Clark, who heads the project, has drafted a proposal to dredge the estuary and dump the silt back in the peatland. Environmental management processes have to be followed first and no timelines have been given.

Meanwhile, Kruger has laid criminal charges against various people at the Overstrand Municipality, DWS and BOCMA. In a public letter he stated: “Overstrand municipal officials repeatedly ignored a court order over a period of more than 30 years, while those that were supposed to have oversight have chosen to look the other way. Stealing water is not a victimless crime. Massive damage was suffered by unique and endangered riparian, wetland and estuarine ecosystems, and while the cost of partial restoration is estimated at hundreds of millions of rands, the lost peat cannot be replaced.”

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: After the fire: Wingfield refugees wish to stay put

Previous: Nelson Mandela Bay reopens bridges damaged during 2024 floods

Letters

Dear Editor

Hemel-en-Aarde Valley is more than a story of environmental loss – it is a national wake-up call. The destruction of this ancient wetland and the Onrus estuary exposes not only ecological tragedy but deep failures in governance, accountability, and public stewardship of our shared water resources.

This disaster cannot be allowed to fade from public attention. I call upon all environmental activists, community groups, scientists, conservation organisations, and concerned citizens – together with all three spheres of government – to unite in an urgent campaign to rehabilitate this devastated ecosystem and to demand accountability for its preventable collapse.

The Overstrand Municipality, the Department of Water and Sanitation, and the Breede-Olifants Catchment Management Agency must work transparently with civil society and local communities to restore the peatland’s natural hydrology, remove invasive vegetation, re-establish ecological baseflows from De Bos Dam, and rehabilitate the Onrus estuary. Independent environmental scientists must lead these interventions, and regular progress reports must be made public.

Equally vital is consequence management. If officials or entities wilfully ignored the 1973 Water Court order or exceeded lawful abstraction limits, they must face civil, administrative, and, where warranted, criminal sanctions. Stealing water and destroying a rare carbon sink is not a victimless act – it has robbed present and future generations of an irreplaceable natural heritage and intensified the climate crisis.

The principles of sustainable development and intergenerational equity enshrined in Section 24 of our Constitution impose a duty on everyone – state and citizen alike – to protect the environment for the benefit of future generations. This catastrophe offers one last opportunity to prove that these principles still have force.

Let the rehabilitation of the Hemel-en-Aarde Valley become a symbol of collective renewal.

© 2025 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.