The difficult exit from the gang

Each step in makes it harder to get out

Calvin* and Mikey* were introduced to gangs when they were very young. Mikey began his initiation into gangsterism shortly after his father was stabbed to death in a gang dispute. His father was part of the 28s prison gang.

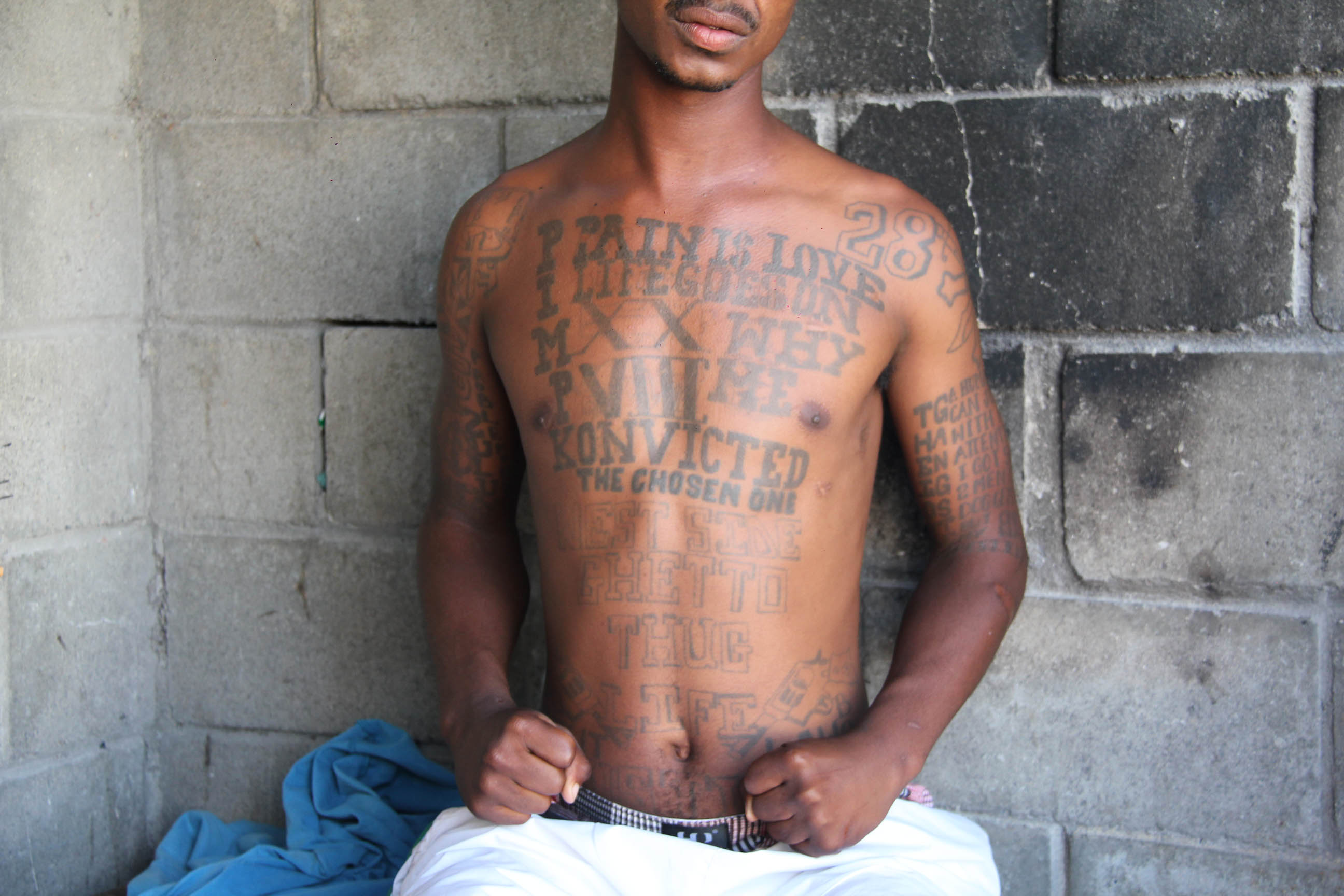

Calvin’s older brother was also a 28, as well as a member of the Mongrels street gang. He was shot when Calvin was 13. Calvin joined the Mongrels to seek revenge, later also becoming a high-ranking member of the 28s while in Pollsmoor.

By 26, Calvin had already served ten years for murder. It is then that he met and started recruiting Mikey, who was ten at the time. “I just came out of prison… [and thought] I’m just going to do what I have to do,” he says. “So I recruited Mikey. I recruited so many people… You know, for me it was like, they recruited me when I was young. So I will just do the same.”

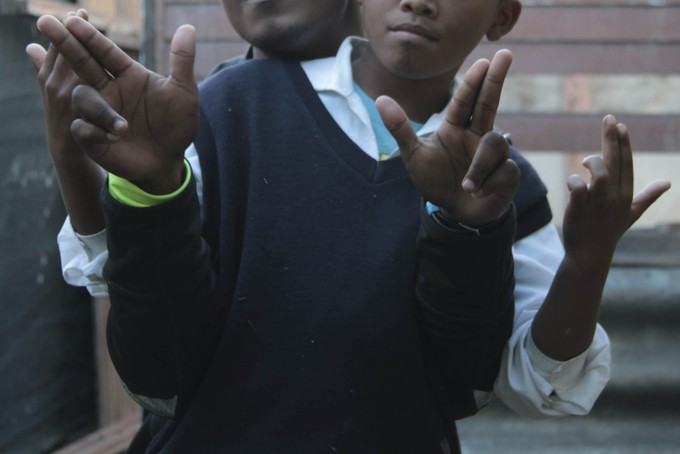

The power associated with gangsterism has an intense appeal for youngsters who are socially and economically marginalised. “They are hitmen [and] powerful. If they call you and you don’t come, they can come to your house and shoot you – dah, dah,” claims Mikey; shooting his hands like guns, as he takes on the exaggerated swagger of a gangster.

Three years after they first met, both want to leave gangs behind. But it’s not easy.

Primed for Violence

Many youngsters are primed for gang life early on. Throughout his extensive research on Cape Flats gangs, criminologist Don Pinnock has found young men typically have fathers who are “absent or aggressive.” He says: “in adolescence, the shame [from lack of paternal support] mixes with anger.” Violent aggression becomes an outlet for this combustible mixture – with the gang providing the flame.

Pinnock also suggests that priming for gang life can begin even before birth. In utero experiences with stress, violence, and substance abuse alter genetic code to create an aggressive, dopamine-driven personality that can survive in a hostile environment like the Cape Flats. According to the criminologist, “Gangs are a perfect shape that fits that kind of personality. They are aggression, bravery, affirmation, gang-boss-father, and family structure.”

However, predisposition is not predestination. Children are actively recruited into gangs. Pinnock says, “It starts really early. Young kids of four or five are sent [by gang members] to the shop to buy a Coke.” These kids might later hide guns or sell drugs, and then eventually be pulled into committing acts of violence.

As it is described by Pinnock, gang membership is unconsciously deepened through the life paths of young men. Each step in makes it a little harder to get out.

“Eventually, even if you thought it was a bad idea, all of your friends are in there. And eventually you’ve done the kinds of things that may get you into trouble.”

Personal security is another key impediment to exiting the gang. “Even if you aven’t killed somebody in the opposing gang… you can be victimised by the other gang just to show that we can take you out,” he explains. “Eventually it seems there’s no way out.”

Struggling to Beat the Odds

But Calvin and Mikey are trying to beat the odds.

Now 13, Mikey has left the gang life behind after his mother and community intervened to push him away from gangsterism. “I knew it was the right thing to do,” he says. “I was going to be dead by now if I was going to carry on with gangsterism.”

Calvin, 29, has also taken steps to leave gangsterism. He received a bursary and is studying film and media, while working on a fledgling rap career.

For Calvin, the dangers of transition are clear and ever-present. In the past two years, he has been shot at numerous times and almost killed. He lives in a context where violence is a norm, and has fought with and stabbed two of his close friends in arguments with them.

“For two years, before I got this bursary, for me it was hectic. The change, I didn’t believe in change. I tried to believe, but things kept getting harder, and harder… Then after that I was like, I’m not going to try again, I’m just going to do it.”

He has been back to prison twice since his initial murder sentence. After the second time, he says, “I came out like two days after my birthday, and I was like, Yo! so many birthdays in jail.” It was then he decided: “This time I was like, it’s not for me.”

But Calvin still has a pending rape case against him – though he insists it is fabricated. The case was brought by the girlfriend of a gang member he had recruited into the Mongrels.

And Calvin’s youngest brother – whom he also made a Mongrel – is an emerging leader in the gang. Calvin feels the need to protect his brother if he is attacked.

But even as Calvin’s past keeps haunting him, he insists: “I’ve got to make peace with my past. Even though I am nothing, I can still be something.” For instance, Calvin recently discovered the identity of his older brother’s murderer; but, as a testament to his commitment to leave gangsterism, he has decided not to retaliate.

Mikey also says he is committed to staying out of gangs. But though he had not been formally recruited into the gang and has no tattoo, he lives in an environment rife with gang violence. Two months ago, a boy he knew was shot and wounded, while another that was with him was shot “through his mouth and through his eye” and killed.

Mikey also has problems at home and at school. His mother is out of work and often does not have money to feed him and his sister. He also admits to smoking dagga and trying tik. After a recent suspension from school for possession of marijuana, he has been threatened with expulsion. If expelled, Mikey may not find another school to take him.

The Long Walk to Freedom

Mikey’s mother Brenda worries about her son. She is especially concerned about living in an environment where there are “lots of kids that don’t work, that don’t go to school,” and instead “steal” and “rob the people”. She thinks parents must take responsibility for their children.

But Brenda knows first-hand the difficulties that parents face. Both Mikey’s brothers are also smoking tik, and the oldest is in a gang. Though Brenda “tried to talk” to her two oldest sons, she says she accepts that they are now “big enough” and “they do their own shit”.

Still she hopes the best for Mikey, wanting him to finish school and go to university. “From the time he found out that his father died, he was very dramatic,” his mother says. “But from now I can see that he’s changed a lot.”

Mikey also says he would like to go to university to maybe become a “businessman, or a politician”. In response to the obstacles he faces, he says he “must work harder and focus”.

Since Mikey didn’t officially enter the gang, he says, he is a “free man” who can “go anywhere and talk to anybody”.

On the other hand, Calvin’s history with gangsterism is a constant threat. “I still don’t walk past the enemy [territory]. I don’t want to commit suicide,” he says. Even when he goes to see family in other areas of Cape Town he must “always find out who is fighting there” to determine which parts of the community are safe to visit.

Calvin regrets joining the gang and recruiting youngsters like Mikey. “Back then I never had, like, emotions, or any shit. Because back then, for me, it was just, like: be out of control. Like I said, I was trapped. I fell into insanity. Into my [older] brother’s life.”

He now aspires to become a famous rapper and have his own label. In doing so, he also wants to set an example for others, “for another kid like me, that is coming from the gutter.”

Calvin captures the harsh contrasts of his hardships and hopes in a song entitled “Inspired Growing,” declaring: “I hustle while I pray / just hoping everyday / that my life will get better / that my aims will get bigger / to shoot for future / I have to pull the trigger.”

But the future is still very much in doubt. After his bursary runs out this year, Calvin will have to find a job – or face the temptation of once again peddling drugs and violence.

* Not their real names.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: South Africa opposed UN resolution on internet access

Previous: South Africa abstains from UN vote to protect human rights

© 2016 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.