Battle to recover R42 billion in unclaimed pension money

Plans to march to Parliament

A campaign to reclaim billions of rands in unclaimed benefits is about to kick into high gear. The Unclaimed Benefits Committee (UBC), representing a group of claimants, and non-profit organisation Open Secrets, are planning to lobby Parliament.

“We will also be calling for a boycott of finance companies involved in withholding benefits,” says Thomas Malakotse, a member of the UBC steering committee. “The fund administrators have been making secret profits for decades by charging fees on these unclaimed assets, and they are accountable to no-one.”

The group plan to march to Parliament early in the new year.

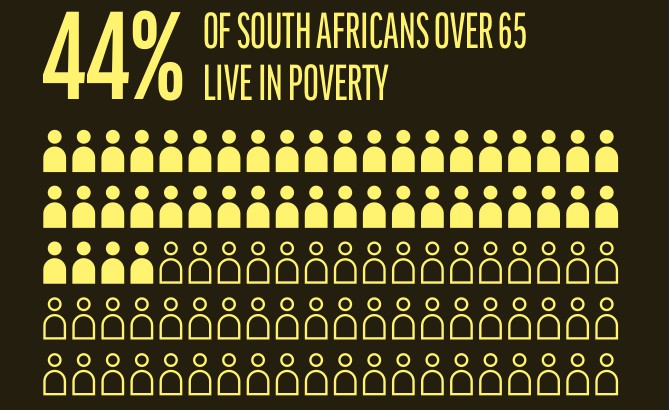

In a recent investigation, Open Secrets found there was R42 billion in unclaimed pension benefits owed to more than four million South Africans, a country where 44% of pensioners live in poverty. If one adds funds not subject to regulation and supervision in terms of the Pension Funds Act, the amount of unclaimed benefits is closer to R51 billion.

Billions then in the financial system belong to people who have yet to be tracked down. Nor does there seem to be much serious effort going into tracking them down. Michael Marchant of Open Secrets says he is surprised that the damning report has not elicited a response from the Financial Services Conduct Authority (FSCA) which is the regulatory body in charge of pension funds (previously the Financial Services Board). Malakotse says the UBC has no intention of allowing the report to be buried.

This is not a typical story of corruption, says the Open Secrets report. It says it stems from the perverse incentives built into the pension fund industry. The administrators – private companies appointed by the trustees – are responsible for chasing down unclaimed benefits but are also the ones who earn hefty fees on administering unclaimed benefits. So long as the pension funds remain unclaimed, the fund administrators can continue to extract fees, year after year.

These funds belong to millions of employees (and their families) who left their jobs, unaware that they had unclaimed pension benefits owed to them. Many of them returned to Zimbabwe, Malawi or other neighbouring countries, often decades ago, leaving their pension benefits behind.

In a discussion document entitled Unpaid Benefits for which Pension and Provident Funds in South Africa are Liable, former Financial Services Board deputy pensions director Rosemary Hunter outlines a few reasons why so many pensioners and their families are unaware of the benefits owing to them.

- failure by employers to inform employees that they were members of retirement funds

- failure to keep retirement fund members up to date on the state of the funds

- failure by members to inform their dependants that they had benefits owing to them

- the requirement that foreign workers leave South Africa after their work permits expire; and

- the practice of some foreign workers adopting different names to obtain work in South Africa.

Malakotse says it doesn’t surprise him that the regulator and the administrators have been sluggish in tracking down beneficiaries. “So long as the beneficiaries remain untraced, everyone makes billions on these unclaimed benefits.”

Based on a conservative charge of 3% a year for fund administration, these unclaimed funds could generate annual fees in excess of R1 billion for the administrators and asset managers.

The Open Secrets report provides a disturbing insight into pension fund practices, and comes after two fairly recent court cases involving pension beneficiaries attempting to hold companies and fund administrators accountable. Both cases – one involving Tongaat pensioners, and the other brought by Hunter – went against the beneficiaries.

In 2016, Hunter took her employer, the Financial Services Board, first to the High Court and then to the Constitutional Court over its deregistration of 4,600 pension funds, many of which still had funds in them. She lost her case in the Constitutional Court after a majority of judges decided that the Board had made efforts to investigate the extent of assets and liabilities in deregistered funds. The judges also argued that there were other remedies available to Hunter. The judgment has been criticised for failing to discharge the court’s constitutional obligation to adequately protect the interests of those prejudiced by cancelling funds.

Malakotse says the UBC has embarked on “a new strategic approach” to “make the FSCA and administrators accountable and transparent when it comes to cancelling funds”.

“We are 100% behind all beneficiaries who are still deprived of access to these benefits. My father was told that he did not qualify for any of his pensionable benefits since he started working in the mines from 1948 to 1975. To date, we are still deprived of access to his benefits. I have been sent from pillar to post by these mine administrators and the FSCA, who claim to have no records of my father. The UBC and Open Secrets will challenge all these administrators and the authorities until they accept their wrongdoing, show transparency, and return to the beneficiaries what is due to them.”

The Open Secrets report says more than 6,000 “dormant” pension funds have been cancelled since 2007, even though some of these still had assets and liabilities.

More than 4,000 of these funds were cancelled at the request of the fund administrators who were “appointed by the regulator to act as representatives or trustees”.

“In their capacity as trustees, they were obliged to make sure that the funds were indeed empty of assets and liabilities and that members were paid before submitting them to be deregistered, but this was often not the case.”

The assets in these cancelled and dormant funds were moved to unclaimed benefit funds held by the fund administrator. Since 2008, the assets of these unclaimed benefit funds increased more than R450 million to R8 billion. The fund administrators continue to earn generous fees on these assets.

“In 2019, well over 16 million South Africans belong to a pension fund. Of these, around 90 percent are members of over 5,000 privately administered pension funds, most of which are run by some of South Africa’s largest financial institutions,” says the Open Secrets report, entitled “The Bottom Line – Who Profits from Unpaid Pensions?”

“Every month, these people give up a portion of their earnings in order to secure a retirement and old age with dignity, and to provide for themselves and their dependents when they can no longer work. These hopes have been dashed for the millions who have not been paid the pensions that they are owed.”

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: High Court orders PRASA to create safety plan for railway security

Previous: No lawyers and no bail: Refugees on trial for trespassing

Letters

Dear Editor

It is indeed a sorry state of affairs when the poor underprivileged masses, who, not because of their own choices, being on the lower end of the income scale, end up being victims of a system designed to enrich the already privileged at the poor`s expense.

Many families go to bed on a half full stomach after the passing of a family head who had sacrificed a portion of his meagre salary as a pension contribution believing that upon his demise, the surviving dependents would not suffer from lack of resources necessary to guarantee a much better life. This situation also serves as an indictment on the powers that be for failing to ensure that those entitled to what is unarguably due to them should indeed be paid to them without any ifs and doubts.

Dear Editor

I'm one of the people who tried to claim the benefits belonging to my father, a migrant worker from Malawi. I communicated with one of the administrators, unfortunately the information they required I don't have since my father passed away.

Why can't a list of all those with benefits be produced so that we can identify names of those who worked in the mines in the 1960s. Most of these migrants were illiterate and didn't keep records of their employment history.

I fully support your efforts to get to the bottom of this issue. Seems the administrators are not making any efforts to locate the beneficiaries.

Dear Editor

I recently discover that my father worked at a mine and I tried to claim these benefits at Alexander Forbes. They want I'd numbers knowing fully well that in the 70 s black people did not have identity numbers. This is just another way to frustrate beneficiaries.

Class action against these companies is the way to tackle this issue. Thanks for bring this problem to the attention of all South Africans.

Dear Editor

I worked on the mines (West Rand Consolidated Mines) in Krugersdorp from 1965 to 1972. I resigned early in 1973. I was approached by Alexander Forbes in Sandton in 2016 to come and claim my unclaimed funds. They required all sorts of information which I duly provided. They then called me to provide a service certificate which they said I could obtain it from TEBA the mine's recruitment Agent.

TEBA sent me from pillar to post and I literally gave up pursuing the matter. My brother also worked on the same mine for a very long period. He has since passed away and I am sure he was not aware of his benefits hence he never received any form of communication from the relevant parties.

© 2019 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.