People living in abandoned Cape Town building face eviction

About 30 people have been living in 104 Darling Street for more than two decades

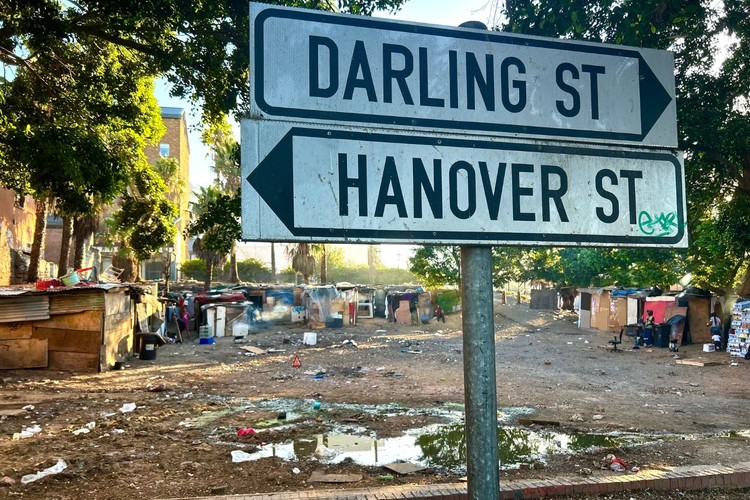

About 30 people are living inside the three-storey building on 104 Darling Street, and dozens more live in an informal settlement in the property’s parking lot. Photos: Matthew Hirsch.

- 104 Darling Street in Central Cape Town is owned by the Department of Public Works, which is releasing the property and accepting proposals for its future use.

- Eviction notices issued by the department state that the building is unsafe. The building has been declared a “problem building” by the City of Cape Town.

- But residents say the building is still safer than elsewhere and that they do not want to move.

Unathi Mangali’s daughter was a baby when they moved into 104 Darling Street in the Cape Town city centre twenty years ago. Today her daughter is 22 years old. They are among about 30 people facing eviction from the property.

The three-storey building is owned by the National Department of Public Works and Infrastructure. It is one of 24 state-owned buildings across the country being released by the department. Eviction notices were issued to residents in February.

When Mangali and her family moved into the building, a shop was still operating from the ground floor, where her mother worked as a cleaner and a cook.

Residents used to rent their rooms from the previous tenant of the building, who was evicted, but the people living in the building were not included in the eviction order. The building was abandoned by the department. In the years since, more people have moved in.

“In 2016, the electricity was cut off. Since then we have been in the building without electricity. Things started getting worse,” Mangali told GroundUp. She said some people left after a fire on the top floor of the building in 2017.

GroundUp visited the site last week. The burned roof of the top floor has been fixed. Several rooms have been boarded up to keep rats out. Windows are broken. Someone has erected a corrugated-iron shack in the hall.

Outside the building, in what used to be the parking lot, there are about 15 informal structures.

Mangali said she was frustrated by the eviction notice. “The unemployment rate is so high. I was retrenched. It’s easier to get a job now because I’m in the city.”

Unathi Mangali moved into the building in 2005 with her daughter, who is now 22 years old.

Safety Concerns

One of the main reasons the department wants to evict the residents is that the building has been declared unsafe. A site inspection was conducted in July 2024 and the site was officially named a problem building by the City of Cape Town last year.

In court papers, the department said it would seek an urgent eviction application on 9 April. The department contends that trees surrounding the building pose a fire hazard and that the “dilapidated building could collapse”. The department owes R100,000 to the municipality for rates and taxes on the building.

“The building has no running water, no electricity, no proper ventilation and no ablution facilities. These living conditions are a health hazard, making the occupants and the children prone to illness,” the court papers read.

A resident has erected a corrugated iron shack in the hall.

Lennox Mabaso, Department of Public Works and Infrastructure spokesperson, said the building will likely be demolished. “It is evident to anyone that the current state of the property is not fit for human occupation,” he told GroundUp.

During a site visit in September, officials from the City and the department did not go inside the building, citing safety concerns. Mangali said she saw them from her balcony.

She says it is still safer in the building than elsewhere. “We just want to be inside. We are not prepared to go anywhere. This is our home. We managed to fix the roof.”

But she added that the building often acts as a hiding place for criminals. Mangali says there is no access control, so anyone can enter the building.

Grace Shauli, who moved into the building during the Covid lockdown, says it was a tough time. “There was a problem with water and the toilets. These skollies steal stuff and get inside. We have been fighting them for a long time.”

“Even though there have been a lot of problems, we manage. If they chase me out it would be a problem to get another place to stay.”

Shauli previously worked at a coffee shop in town which has gone out of business.

Dozens of people live in the informal settlement in what used to be the building’s parking lot.

Request for proposals

In December Public Works Minister Dean Macpherson announced the release of 24 state-owned properties across the country. Public and private entities have been asked for proposals. The deadline for proposals is March 13.

“We are hoping to use these properties as an example of what can be achieved with underutilised state-owned properties country-wide. This process signals a shift from the department that previously hung onto properties despite serving no purpose. With this programme, the era of state-owned buildings standing empty, attracting crime to communities and chasing away investment is ending,” Macpherson said in a statement.

After a visit to 104 Darling Street in September, Cape Town Mayor Geordin Hill-Lewis said in a statement that a new joint technical committee would help fast-track resolutions to problem buildings owned by the state.

“There are several rundown state-owned buildings in Cape Town that are a source of crime, and a blight on neighbourhoods … Some of these buildings and land parcels could be released for affordable housing, while others should simply be demolished or sold so that they can be put to more productive use,” he said.

One of the dilapidated bathrooms on the property.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Here’s how a disabled person spent their grant

Previous: Allegations of fraudulent payments amounting to billions at PRASA

Letters

Dear Editor

To the Mayor of Cape Town

You say the City works for you. People gets evicted every day in this province – more people on the streets. Why not just reconstruct the building into a community center to help keep some of the people off the streets? Stop selling government premises and properties. You want to brag how much you do for the city on social media platforms. Stop degrading people by pushing them more and more into poverty. Crime is already escalating day by day because of these acts. Start helping the less fortunate. How many people have to suffer still in this country? Shame on you all that are in power.

Dear Editor

This letter is to the City officials:

I've read through the article. Nowhere does it state what your plans are to provide housing solutions for the people you are evicting.

Strange enough, this specific building was pointed out to me and my sisters less than a month ago by our Uber driver.

Maybe you should then supply an alternative safer place for the inhabitants. Their livelihood matters. Not just money.

© 2025 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.