What needs to be done about Cape Town’s water crisis

“Decision making … is now lagging too far behind our current reality”

This is part four of a GroundUp special series on Cape Town’s water crisis.

What’s being done

Restrictions

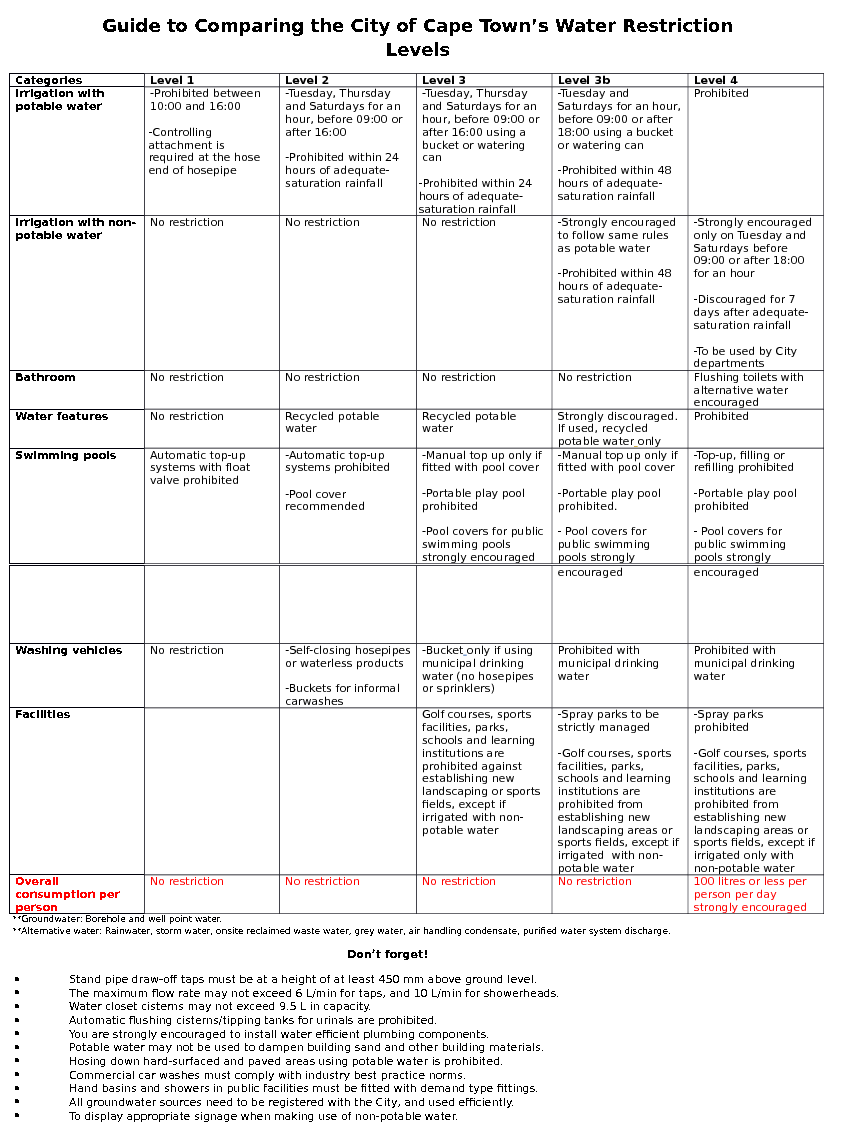

The City of Cape Town began implementing Level 2 water restrictions on 1 January, 2016, escalating to Level 3 on 1 November and 3B on 1 February, 2017. (See table at bottom of article.)

On 16 May, City officials announced their recommendation for the implementation of level 4 water restrictions. If ratified by Council, the measures, to go into effect on 1 June, ban the use of all municipal water for outside and non-essential use.

“Every drop of drinkable water should not be used for anything else. It should just be kept for drinking purposes only,” Executive Mayor Patricia de Lille said at a water briefing on 9 May.

The City has also pledged to continue cutting water pressure and reducing water waste via leakage. The City currently believes leakage waste to be below 15%, but has set a goal of reducing that number to between 5% and 10%.

Infrastructure development

According to the Mayco Member responsible for water, Xanthea Limberg, the City is either considering or developing alternate water “augmentation schemes such as aquifer extraction, desalination plants, water reclamation, and expansion of surface water [projects].” Limberg said that infrastructure development is planned for the next “20 to 30 years,” but is “being accelerated under the provisions of the declaration of a local disaster area.”

But Limberg and other city officials emphasise that surface water dams are still the main component of Cape Town’s water supply. “In the medium to long term, even with development of non-surface water sources, our surface water dams will still make up the majority of the region’s water supply, and therefore some form of restrictions during droughts will be inevitable for the foreseeable future,” Limberg said. “Non-surface water schemes are much more expensive to implement, and as such a water supply system that could completely shield residents from the effects of drought is not feasible.”

What needs to be done

An escalation of restrictions

Experts agree that the city should have applied water restrictions faster, and needs to move to Level 4 restrictions immediately.

“With hindsight, there is no doubt that the restrictions should have been implemented earlier. October 2016 should have been the first warning sign,” Kevin Winter, a researcher with the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Environmental and Geographical Sciences Department, said. “I think the City held back a little too long in the hope that it would rain a lot earlier.”

Christine Colvin is the Senior Manager of Freshwater Programmes at World Wildlife Fund South Africa’s Cape Town office (WWF-SA). She said that waiting any longer to implement Level 4 restrictions, even until the next Mayco meeting, could be detrimental.

“The City needs to actively enforce Level 4 restrictions as soon as possible,” said Colvin. “There is literally not a day left to lose.”

Equitable application of restrictions

Groups like Environmental Monitoring Group (EMG) also say that current water restrictions unfairly target the poor and need to be applied equally across Cape Town.

While Level 3B restrictions allow swimming pool top ups, so long as the pool is fitted with a cover, “indigent water allocation” is limited to 350 litres per day. The water consumption limit is enforced through the installation of city-owned water management devices which shut off access to water once 350 litres is reached.

Proposed Level 4 restrictions “strongly encourage” all Capetonians to limit themselves to consumption of 100 litres of water per day per person, but it is not enforced. Indigent water allocation remains at 350 litres, but is forcibly applied and amounts to less that 100 litres per person per day for households larger than three people.

“At this stage in the water crisis there should probably be water rationing,” said Taryn Pereira, a staff member with EMG. “But it should be rationing for all.”

Aggressive infrastructure development

Academics and experts are now calling on the City to develop an “integrated water system” to service Cape Town. The system would combine the harvesting and use of surface water, groundwater, stormwater, greywater, effluent water, and rainwater. It would also emphasise processes like desalination, groundwater recharge, and water reuse.

“In the long term, relying on surface water infrastructure only won’t be sustainable,” Colvin said. “Climate change predictions indicate that droughts will become more frequent and temperatures will rise in the region. This means that dams will not be fully replenished… Future-proofed water infrastructure needs to include a greater proportion of well managed groundwater and re-used water.”

WWF-SA is also calling on government to better manage the “ecological infrastructure” of “water source areas,” parts of the Western Cape that feed Cape Town’s dams. These areas are threatened by invasive plant species that consume significant amounts of water and create a wildfire hazard.

Winter said the integrated system would be designed to “keep water in the city” and include green roofs capable of filtering and cleaning water, rain tanks for precipitation collection, greywater and stormwater recycling systems, as well as open spaces replacing hard surfaces for infiltration to take place.

Both Colvin and Winter agree that the city needs to move fast.

“Most of the options on the cards for additional alternate water sources in the near future will not be operationalised in time to deal with this drought,” Colvin said. “Better plans and management models have been in conception for many years, in some cases decades… Decision making and operationalisation is now lagging too far behind our current reality.”

Better communication

As reported by GroundUp, data on the drought is difficult to find. Winter said the City has been engaging more with the media and academic community than in previous drought years, but that information needed to be filtered to citizens.

He said that water bills should include information on how a household is using water compared to the average use of households of similar size. “We’ve now got systems in place where we should be able to get individualised feedback on the bills which indicates your water use,” Winter said. “You should know what you household is doing.”

More help from national government

Limberg said the City was “committed to working with the National Department of Water and Sanitation” to move forward with solutions to the water crisis. “The City needs the National Department to bring forward the implementation date for the Voelvlei Augmentation scheme to add more water to the system of dams on which the municipalities and agriculture in the region are wholly dependent.”

“In addition, we expect water use licences to be rapidly processed for the non-surface water augmentation schemes being implemented by the City to prevent implementation delays.”

CORRECTION: One of the quotes for Taryn Pereira was changed after publication.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Why protests become violent

Previous: Judge defends his behaviour in case to have him replaced

Letters

Dear Editor

Where is the discussion on the public health crisis this is and will be causing? Which agencies have been testing the water for bacterial contamination and neighbourhoods likely to be effected to determine our current level of risk? Why aren't we hearing about Eskom subsidies to provide the electricity needed to boil water? Water is life, why don't we hear from more public health experts about how the current unequal restrictions are impacting the poor? Where is the department of health? There is little to no communication about this crisis and what can be done from them.

© 2017 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.