Sick mine workers neglected - time to compensate them

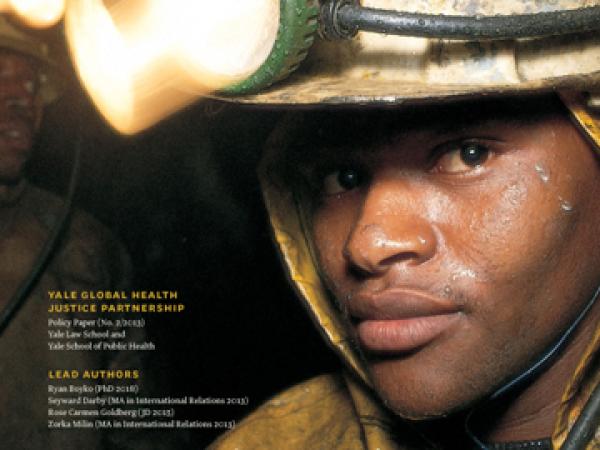

Far from the bustling streets of downtown Johannesburg, much of it built by the bounty of South Africa’s gold mines, thousands of former mineworkers suffer from painful diseases contracted on the job. These men labour to breathe, their lungs degraded by the occupational diseases of silicosis and tuberculosis.

The men’s bodies waste away, making even simple household chores painful, and paid work all but impossible. Many of them will die from their illnesses, leaving destitute families behind.

For many mineworkers, disease is the only lasting thing they bring home from the mines. Although they are owed government compensation, few ever receive it. For decades, both government and industry have largely ignored their plight.

This unacceptable neglect is correctable. Our report offers constructive, informed suggestions for reform based on a hard look at the failing compensation system.

More than 700,000 cases of statutorily compensable lung disease in former mineworkers remain unpaid.

Mineworkers actually have special legal rights to compensation, yet they are still denied their vital benefits. According to South African law, mineworkers who acquire silicosis or tuberculosis while employed by gold companies qualify for benefits, including money from government compensation coffers. Funding is supposed to be provided by the mining industry for the explicit purpose of helping men and their families cope with occupational disease. But every step of the process mineworkers must go through to access this compensation is broken. As a result, according to recent estimates, more than 700,000 cases of statutorily compensable lung disease in former mineworkers remain unpaid.

South African law treats mineworkers differently from workers in other sectors, guaranteeing them less compensation for lung disease. Moreover, the government coffers that do exist for mineworkers are woefully underfunded. The lump sum payments mineworkers or their families receive, between R48,000 and R180,000, is inadequate, comprising less than a year’s income and benefits for a median mineworker. An enormous backlog of claims means that only a small percentage of those who apply for compensation ever get even this. In one recent year, the government accepted 28,161 claims while paying only 400.

The Medical Bureau for Occupational Disease (MBOD) is largely responsible for this shamefully low payment rate. MBOD is the government agency responsible for certifying occupational lung disease in mineworkers, and it is ill-equipped to fulfill its narrow but important mission. Its offices have towering stacks of claim records requiring evaluation, including records filed as far back as the mid-20th century.

Despite cheaply available fingerprint identification software, the MBOD still uses a time-consuming process of manual fingerprint comparison, requiring a full workday to process a single set of fingerprints. This step alone limits the government to paying only a few hundred claims per year.

The entire claims process is riddled with such flaws. Proving both illness and employment requires documentation many men do not have, as well as expensive, difficult journeys to visit mining offices or doctors. Although South African law requires free medical exams for former mineworkers, they are often unavailable for men outside cities and for migrant mine workers from Swaziland and Lesotho.

Although South African law requires free medical exams for former mineworkers, they are often unavailable for men outside cities and for migrant mine workers from Swaziland and Lesotho.

The government also requires that the families of mineworkers who die before having their illnesses certified send the deceased’s cardiorespiratory organs to Johannesburg for examination. This is a logistically and emotionally difficult proposition that can serve as a barrier for people whose cultural beliefs prevent autopsy or for those far away from organ collection bins.

Such a complex tragedy of a system might seem impossible to reform. But there are concrete steps, outlined in our report, that can be taken to ensure that mineworkers and their families are treated with dignity and fairness. Our analysis is based on interviews with occupational disease experts, labour and health rights advocates, government officials, and mineworkers and their families. We also examined compensation systems in several other countries, to provide a comparative perspective highlighting components of successful compensation schemes that could work in South Africa. We prepared this report under the umbrella of the Global Health Justice Partnership, an initiative at Yale University.

With increased financing from mining companies, mobile clinics coupled with targeted outreach efforts, increased payments including pensions, and reform of government bureaucracy, including better accountability mechanisms, South Africa could create a fair system of compensation for its miners.

Nothing can make up for the years of life lost by those who have suffered waiting for these changes. The promises of the past are irrevocably broken. But reforming the South African compensation system today would go a long way toward ensuring better, healthier lives for mineworkers and their families tomorrow. It’s time to start fulfilling broken promises.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.