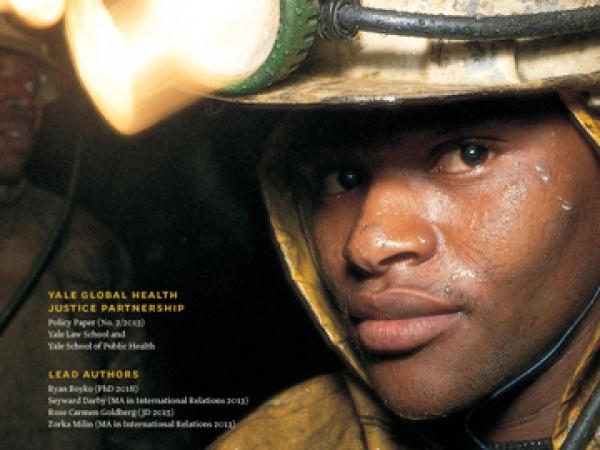

The scandal of South Africa’s sick miners

Human rights lawyers have been engaged for ten years in a bid to secure massive damages for former gold miners who suffer from silicosis and TB. As the case heads for the courts, the mining industry is scrambling to offer its own and much less comprehensive solution.

Too sick to work, cared for by women and families who can barely scratch a living, hundreds of thousands of former gold miners number among the disabled, dying and dead victims of an inadequate compensation system.

This issue, brushed under the carpet during the apartheid era, has become public after 20 years of democracy, against all efforts by the mining companies to keep it buried.

Over the past century, South Africa developed a legislated system for the compensation of workers who are injured at work, or who contract an occupational disease, in line with conventions developed over time by the International Labour Organisation.

Such systems are supposed to provide workers (and their dependent spouses and children) with a lump sum or pension for permanent disability, and lost wages for temporary disability. They are also supposed to cover medical costs of treatment, care, and rehabilitation.

The compensation is paid from a fund fed by a levy on employers who are required by law to pay contributions based on their wage bill.

Former miners suffering from silicosis and TB as a result of their work on the gold mines have launched a claim for damages.

The law prescribes how claims must be lodged; what documentation must be included; what occupational diseases are recognised; how “impairment” is categorised to determine payouts; and sets out an appeals procedure.

The system indemnifies employers against civil suit for damages by individuals or groups of injured or sick workers.

Administration and adjudication is supposed to be independent of workers and employers, and the State has fiduciary responsibility for the funds. The fund must be able to meet present and future costs of compensation to workers and their dependants, and its officers are accountable to Parliament and to the executive branch of government.

South Africa’s system of compensation for occupational injury and disease has, from the start, been divided into two strands – one for mining, and one for other industries. In the mining sector, ODIMWA (Occupational Diseases in Mines and Works Act) gives overarching responsibility to the Department of Health. It provides solely for respiratory disease due to respirable silica dust inhalation in mines, meaning silicosis and tuberculosis, both of which have reached epidemic proportions among workers in gold mining.

During the late 1990s, two ground-breaking prevalence studies for silico-tuberculosis were conducted among former mine workers in the Transkei region, and in Botswana. The studies found a high prevalence rate of these diseases, and estimated the liability to the ODIMWA fund for all living ex-miners in Southern Africa to be almost R10 billion in 1998. This money would be due to several hundreds of thousands of sick South African men (leaving out former miners in other countries). Many of them are unable to work even on their own small holdings to provide food for domestic consumption, and need care by family members (women), whose own ability to earn income is compromised.

But in 2004, the compensation fund under ODIMWA was audited as technically bankrupt, even without taking into account these unregistered claims. The auditors recommended raising employer contributions one-hundred-fold over 15 years to cover even the existing liabilities of the fund.

The Compensation Commissioner appointed under ODIMWA attempted to raise the contribution rate 15-fold, but this was met with a court challenge by the Chamber of Mines, which was willing to allow only a tripling of the contributions by its members.

The Chamber pointed out that many of the companies responsible for the liabilities no longer existed. In other words, as a result of the complicated and changing relationships between legal entities in the South African mining industry, there was no longer any link between the current burden of disease and compensation fund contributions.

The implication was that the State would have to meet the shortfall, as it had often done in the past. In the event, the High Court ruled that employer contributions should be raised 10-fold, which would raise the annual levy from employers in the industry from the current R130 million to R1.3 billion by 2019.

But will even this money be allocated to former miners?

Medical professionals do not understand the compensation system very well, if at all; former miners do not know their rights to compensation because no institutions, especially not the mining houses for whom they toiled, deemed it necessary to inform them; and it is very difficult for them to get access to diagnostic and administrative facilities to make claims.

The mining industry’s own estimates of the success rates for claims submitted by mine hospitals while workers were still in service were as low as 33% in 1980, and a specialist occupational health clinic reported even lower success rate of 20% for former miners in the 12 years to 2010, with an average settlement delay of over four years per claim.

In the face of the failure by the mines and the ODIMWA compensation system to compensate sick ex-miners, mineworkers have launched their own claims for civil damages.

The first case was launched a decade or so ago on behalf of around 30 ex-mineworkers who had spent significant stretches of their mining career at one of Anglo American’s mines, President Steyn mine, and who had contracted compensable respiratory disease. This case was designed to target Anglo, not as the employer, but as an occupational health and safety consultant to the mine.

This is the formal contractual relationship between Anglo and its individual “clients” which own the mines and directly employ the workers. This strategy allowed the claimants to avoid the protection that ODIMWA gives direct employers against civil damages suits for negligence. The case was recently resolved by means of a confidential out-of-court settlement for the surviving members of the group – about one quarter of them had died during the litigation phase.

Such an out-of-court settlement cannot be used as legal precedent and, especially, does not amount to an acknowledgement of negligence, or even responsibility, by Anglo. The terms of the agreement must forever remain secret, failing which it can be withdrawn.

The second case, which is potentially explosive for the mining industry, is being conducted by the South African legal firm Richard Spoor Inc. in conjunction with a public interest American firm called Motley Rice LLC.

In 2011, as part of the case, the lawyers won a Constitutional Court ruling that workers with silico-tuberculosis could sue their employers for damages due to negligence, even if those employers were covered by ODIMWA.

Thirty-two of the largest mining companies are named as respondents in the class action attempt, and a conservative estimate of the numbers of sick workers in the class is 100,000 to 200,000.

“So far we have contacted 28,000 ex-mineworkers with more than 10 years service in mining, and who have a respiratory disease,” Spoor told GroundUp. “Of these, about 5% (about 1,400) have had medical diagnoses. Those whose disease is diagnosed will be representatives for the entire class in a class action suit.”

“One class will be those with silicosis with or without active TB, the other will be those with TB without silicosis. Both classes will include damages due to the dependants of mineworkers who have died whilst the litigation is continuing”, he said.

A hearing is set for 12 October 2015 in the South Gauteng High Court to decide on the application for a class action.

Spoor said he hoped the court would rule that sick former miners who met the criteria would automatically be included in the action, unless they did not wish to be.

In view of these developments, the Chamber of Mines made an attempt to gain the moral high ground late last year. In a press statement in November 2014, the Chamber announced the formation of an Industry Working Group consisting of five major mining companies which are respondents in several legal claims for negligence and damages.

The Chamber was careful to state that these companies “do not believe they are liable in respect of the claims brought, and they are defending these. They do however, believe that they should work together to seek a solution to this South African mining legacy issue”. .

When this statement was made, the Chamber of Mines was already working with the Department of Health, responsible jointly with the industry for the administration of ODIMWA, on “Project Ku-Riha”. This involved the launch of two “one-stop service centres” in Carletonville and Mthatha to help sick mineworkers make new claims under ODIMWA, and to speed up existing backlogged claims,

Last month, the Minister of Health, Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi, announced that R1.5 billion would be paid out from the R2.9 billion ODIMWA compensation fund to an estimated 500,000 ex-miners with compensable lung disease, from all over Southern Africa.

Project Ku-Riha, still in its pilot phase, is designed to make this possible by providing the complex necessary diagnostic and administrative support. Some of the companies in the Industry Working Group and named in the class action suit have clubbed together to give R5 million to employ a project manager and staff on Project Ku-Riha. Motsoaledi said the project had the support of the mines and all the major trade unions in the industry.

It remains to be seen how easy scattered, poverty-stricken and disabled former miners in South Africa and surrounding states will find access to this initiative.

It should be noted that R1.5 billion between 500,000 people amounts to an average (not a minimum) payout of only R3,000. The R1.5 billion should also be compared to the epidemiologists’ estimate of nearly R10 billion needed in 1998, though it is not known how many of those who would have qualified for compensation have since died.

Gold and other mining in rock with high silica levels in South Africa continues. In 2008, after much discussion between the mining industry and Department of Minerals and Energy officials, a “zero harm” policy was adopted, ostensibly to reduce drastically the number of miners contracting ODIMWA diseases. But dust measurements are still highly contested and the impact of this policy will only be available at least 10 years, and in most cases, 15 to 20 years on, assuming that all ex-miners receive the diagnoses, follow up examinations and autopsies to which they are entitled under ODIMWA. Employment in the gold industry is shrinking, and likely to decline even further, which will reduce the sheer magnitude of the problem in future.

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking for the hundreds of thousands of former miners waiting for compensation to which they have always been entitled.

Both the mining industry and the State compensation system have failed them miserably. It is not a coincidence that the initiative under way, praiseworthy though it may prove to be, comes as the mining industry heads towards a court case which might significantly affect share values.

Pete Lewis is a former senior researcher at the Industrial Health Research Unit at the University of Cape Town. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. No inference should be made on whether these reflect the editorial position of GroundUp.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Previous: SAPS twice as lethal as US police

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.