The myth of the lady with the lamp

Nursing unions and the media noted last week that Monday was a day dedicated to nurses, to those who treat the sick and the ailing. And, as they did so, they continued to perpetuate a myth.

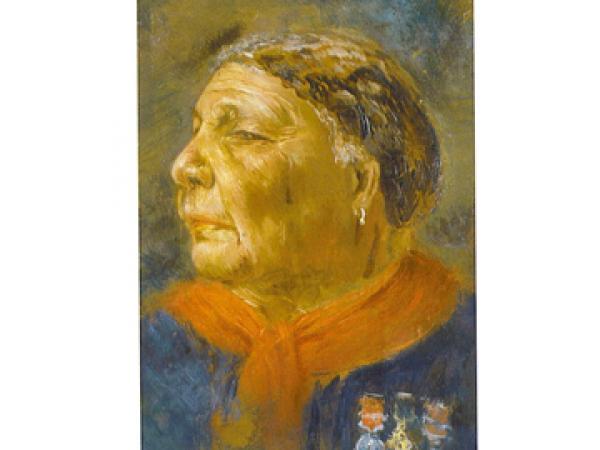

The myth is that Florence Nightingale, was the unique “lady with the lamp”, who tended to wounded, sick and dying British soldiers in the thick of the Crimean war. Yet Florence Nightingale was not the only or even the original “lady with the lamp”; that accolade belongs as much to Mary Seacole whose contribution has been buried beneath more than a century of racist and imperial myth making.

A black woman and a Roman Catholic from a working class background, she triumphed against the race, class and religious bias that was rampant in the male-dominated and Protestant British empire. As such, she provides a great role model for health workers everywhere.

Yet neither the Democratic Nursing Organisation of South Africa, the largest of three Cosatu-affiliated unions that organises nurses, nor any of the other nursing organisations in South Africa, last week even acknowledged the existence of Seacole. And a commercial skin care brand presented its fourth “Florence Nightingale Awards for Excellence in Nursing” to “women who go beyond the call of duty”.

However, it is only in the past decade that the story of Mary Seacole has emerged again in Britain, often counterposed with that of Florence Nightingale. But both Seacole and Nightingale deserve recognition, Mary Seacole as possibly the world’s first nurse practitioner and Nightingale as a wartime nurse and founder of a nursing college in the post Crimea war years.

Over more than a century, the contribution of Mary Seacole has been melded with that of Florence Nightingale to manufacture the myth of the pale-skinned, white garbed lady with the lamp, an angel incarnate. But all who worked, men and women, tending the wounded and sick in the battlefield treatment stations — not only Nightingale and Seacole — carried lamps at night.

After that war, in a region that is again in the world headlines, Mary Seacole was hailed as a hero. She was also acknowledged, alongside Nightingale, for developing the profession of nursing.

Born in Jamaica, the daughter of a Scottish soldier and an Afro-Caribbean “doctoress”, she learned her skills both from her mother and “on the job” because acial iscrimination denied her the right to formally enter any profession.

However, she soon made her mark, working with military surgeons, nursing and “doctoring” to soldiers in different parts of the Caribbean. She was also before her time, because she was known successfully to complement her knowledge of traditional medicine with European medical ideas.

Travelling widely, she collected glowing testimonials for her work with the sick and wounded, and when regiments were drafted from Jamaica to Crimea, she followed to offer her help. But despite the commendations she had received, the British army turned her down. So she turned to Florence Nightingale’s organisation of women nurses — and was also rejected.

As she noted in her 1857 autobiography: “Did these ladies shrink from accepting my aid because my blood flowed beneath a somewhat duskier skin than theirs?” So she financed her own way to Crimea, where she set up her clinics, sometimes literally on the front lines.

These were actions that made her famous among the troops and won her accolades from some of the the leading British commanders. Mary Seacole became a household name in Britain as the media of the day, in the form of the famous chronicler of that war, William Howard Russell hailed her.

In an 1856 report for The Times of London, Russell wrote: “I have witnessed her devotion and courage….and I trust that England will never forget one who has nursed her sick, who has sought out her wounded to aid and succour them and who performed the last offices for some of her illustrious dead.”

But in the decades after the Crimean war, England did not so much forget as revise, distort and rewrite history. The name and work of Mary Seacole all but disappeared from the nursing narrative to be replaced by a prim and prissy image of Florence Nightingale, an angelic lady with the lamp.

However, this was the heyday of empire when even the suicidally stupid cavalry charge of the Light Brigade against Russian cannons passed poetically into legend as heroic. Such myths served a bygone era. Today trade unions in particular, should look — and learn — from reality. And there is much to learn from the story of Mary Seacole.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: “Now I can’t afford groceries” - grant recipient after illegal debt deductions

Previous: Mother and disabled daughter face deportation after going to hospital

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.