Land spat highlights tension between traditional and formal law

It’s often unclear who owns land in traditional communities — the individual or the traditional authority

Phathutshedzo Mukwevho stands next to the demolished structure of Humbulani Nenzhelele. Photo: Maanda Bele

- Humbulani Nenzhelele from Tshandama in Limpopo says his partially built home was unlawfully demolished on the orders of the headman.

- The headman’s office says Nenzhelele did not lawfully own the property.

- The case, which is to be referred to the Director of Public Prosecutions, illustrates the confusion over who owns land in traditional communities.

A dispute over ownership of a piece of land in Tshandama village, outside Thohoyandou in Limpopo, has once again highlighted the murky intersection between traditional laws and formal land ownership laws in tribal areas.

At the centre of the controversy is Humbulani Nenzhelele, a lifelong resident of Tshandama, who claims that his partially built home was unlawfully demolished on the orders of Headman Takalani Netshandama. Nenzhelele alleges that the headman and his subjects forcibly stopped construction on his stand, issued threats of eviction, and began demolishing structures — all without a court order.

“I was born and raised in Tshandama. My family has lived and died here. I respect traditional leadership, but what is happening to me is unlawful and unconstitutional,” said Nenzhelele.

He said he had paid R6,000 for the stand and then spent roughly R500,000 on building the house. “I was building my house for my family – and my future plan was to run or establish a business from there,” he said.

The headman’s spokesperson, Phathutshedzo Mukwevho, confirmed that the structure had been demolished but claimed that Nenzhelele had erected a residential home on a business stand. He also argued that Nenzhelele had not legally acquired the property.

“The person who sold him the stand did not own it. We called him to the traditional court several times, but he refused to appear. We have a constitution that allows us to demolish structures built unlawfully,” Mukwevho said.

A grey area

The challenge faced by traditional authorities in enforcing planning and maintaining building standards has been under discussion for some time. In March this year, Limpopo Mirror reported on a case in Madombidzha, near Louis Trichardt, where a local councillor built rental apartments across a public road.

Jeaneth Matumba, an ANC councillor who also serves on the municipality’s executive committee, extended the boundaries of her site, blocking access to the road. The chairperson of the Sinthumule Tribal Council, Makhado Sinthumule, accused her of not following the correct procedures. He promised an investigation, but none of the buildings have been demolished.

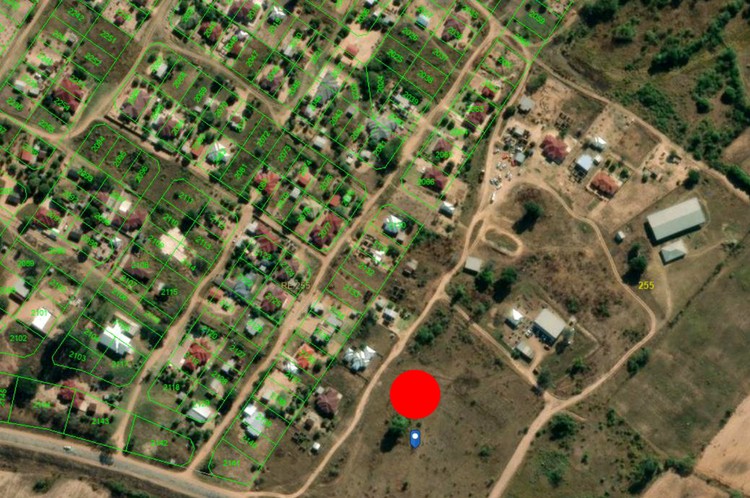

Based on the coordinates sent to us, Nenzhelele’s house was built in an open area. Maps used by the Chief Surveyor General show that it is open veld. Photo: Google Maps (fair use)

Matumba’s case illustrates how municipal by-laws regulating construction are often ignored in remote areas under the jurisdiction of traditional authorities. No building plans are submitted, and local traditional councils often lack the technical expertise to assess whether a building is safe for occupation.

But there is also a flipside, which makes the news every now and then. In April 2024, Limpopo Mirror reported on the plight of Russell Ratombo, from an area described as Komati village near Vleifontein. Ratombo’s house was demolished, presumably for being built without the necessary authorisation. He claimed to have bought the stand in 2007 from a woman residing in Nzhelele and paid her R7,000. The person said to be behind the demolition was the seemingly self-appointed “headman”, Patrick Sambo.

Even though Sambo was not officially recognised as a traditional leader, Ratombo had to accept the outcome and lost his house.

Land ownership in tribal areas: a thorny issue

In Nenzhelele’s case, he believes he was fully within his rights to build the house and the traditional authority had no legal right to demolish it without following proper procedures. He said he paid for the stand but was still waiting to obtain what is referred to as a PTO (Permission to Occupy) certificate.

After his property was demolished, he laid a charge with the Mutale police in terms of the Prevention of Illegal Eviction from and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act, which prohibits evictions or demolitions without a court order.

Nenzhelele said he was deeply disappointed with the response he received from the police and state prosecutors.

“I promptly reported the matter to Mutale SAPS, providing credible, direct eyewitness testimony. And yet, no arrest has been made. No charges laid. No justice served. Worse still, the headman continues to walk freely, boasting that he is ‘untouchable’,” said Nenzhelele.

Frustrated with the Mutale state prosecutor, he approached the Chief Prosecutor, Rudzani Muvhulawa, stationed in Louis Trichardt.

“I personally witnessed the suspect, accompanied by three young men, vandalising my property and stealing some of my belongings on site,” he said in his complaint to Muvhulawa. “This act was carried out without any court order or legal authorisation. As a result, I am now permanently evicted from my home and banned from the village, while the suspect reportedly continues to boast publicly about the demolition.”

Muvhulawa confirmed that the docket had been brought to his office. He said he would study it and prepare a report for the Director of Public Prosecutions.

S. Mzinyathi, Acting Deputy National Director of Public Prosecutions, also responded to Nenzhelele, urging him to exercise patience and allow the law to take its course.

A conflict of different types of law

The Tshandama case reflects a larger, unresolved issue across the country: Who actually owns land in traditional communities — the individual or the traditional authority?

For decades — and in the case of the former Venda, for centuries — land in these areas has been held communally under the custodianship of chiefs and headmen. However, the Upgrading of Land Tenure Rights Act (ULTRA), first enacted in 1991, sought to give all South Africans, irrespective of where they live, full ownership rights.

The amended ULTRA, which came into effect in June 2024, provides for a more formal system of ownership through Customary Land Grant Deeds, to be registered with the Deeds Registry via local land boards. These boards serve as a bridge between traditional leadership structures and the national land administration system.

Under the new framework, residents of traditional areas must apply at a Land Board Office for a Customary Land Grant Deed, which confirms ownership and can be transferred like any other title deed. The land board must ensure that transactions are legitimate, fair, and transparent. Traditional councils are expected to recommend, not unilaterally allocate or revoke, land rights.

Despite these legal safeguards, the reality on the ground often looks very different. Many residents remain unaware of their right to secure a Customary Land Grant Deed, and in practice, traditional authorities still wield enormous control over land allocation.

There are also practical stumbling blocks, such as the fact that large parts of Vhembe have still not been properly surveyed. There are no detailed maps indicating the boundaries of the sites people occupy.

A search on the official maps used by the Chief Surveyor General shows that the site that Nenzhelele acquired is indicated as open veld, not yet mapped. Even if he had wanted to do so, he would have battled to obtain a Customary Land Grant Deed.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Let them eat kreef!

Letters

Dear Editor

I am currently studying towards an LLM in Environmental Law at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. Our Land Use and Planning module teaches that municipal by-laws and land-use planning schemes now apply wall-to-wall across all municipal wards. Yet, as your recent article insightfully observed, a persistent tension remains between land ownership, planning, and use in urban and rural areas.

During apartheid, spatial planning and development policies deliberately excluded and underdeveloped rural communities. In contrast, our constitutional democracy requires municipalities to adopt integrated development plans and spatial development frameworks that apply across both urban and rural spaces. However, these frameworks often have no binding legal status, making them effectively unenforceable in areas where customary law, culture, and tradition continue to govern land use and development.

This raises a crucial question: who truly governs rural land – the traditional leaders or the municipal authorities? And which legal framework prevails? The answer is vital for achieving equitable and sustainable development across South Africa.

Would you like me to draft a one-sentence author bio (as GroundUp often includes short contributor lines such as “Madikizela is a magistrate and LLM student at UKZN”) to accompany the publication?

© 2025 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.