Here is the list of art destroyed on UCT

David Goldblatt and Breyten Breytenbach condemn “censorship”

In addition to a list of 75 art works removed by the University of Cape Town (UCT), GroundUp has now obtained a list of artworks destroyed in the Shackville protests last year and a list of works deemed to be problematic by student representatives on the Artworks Task Team (ATT) in 2015. The list was obtained from the university via a PAIA request (Promotion of Access to Information Act) submitted by William Daniels, a UCT staff member.

The university refused to reveal the titles to GroundUp, but we have, with assistance, worked out most of the titles.

Various artists, including David Goldblatt, Willie Bester, and Breyten Breytenbach, have criticised UCT’s response to student pressure to remove statues, busts, and other works of art from campus.

“In September of last year I wrote to Max Price and said that I wished to revoke my contract with the university,” said Goldblatt, a world renowned photographer whose work exposed the oppression of apartheid. Goldblatt’s decision to remove his collection of photographs from the Libraries Special Collections, a centre that he helped to establish, came after “the throwing of shit onto Cecil John Rhodes’ sculpture… following that the burning of over 20 paintings and the burning, in particular of two photographs by Molly Blackburn.” Blackburn was an anti-apartheid activist who died in a motor vehicle accident that some suspect was caused by the apartheid government.

Goldblatt said that the events signaled a new tide in the development of anti-democratic thought in today’s youth. “Differences are settled by talk. You don’t threaten with guns. You don’t threaten with fists. You don’t burn. You don’t destroy. You talk. These actions of the students are the antithesis of democratic action,” he said.

“For me, the essential issue was that [the university] was in breach of my freedom of expression. I couldn’t leave my work there… to leave my work there would be to endorse that policy,” said Goldblatt.

Breyten Breytenbach, whose Hovering Dog is on the list of works identified as unacceptable by students on the task team, has had three paintings removed and put into indefinite storage by the university.

Breytenbach wrote to GroundUp: “I fully support the decision of David Goldblatt and others to withdraw / remove / take back / take elsewhere (preferably out of the country altogether) whatever material or artworks they may have had at UCT, or were kept in custodianship by the university.”

He said: “If I could do the same, I’d do so.”

Unlike Goldblatt, Breytenbach’s works are part of the Hans Porer Collection at UCT. “None of these parties – collector, owner, executor or executioner – bothered to even have the simple decency of informing me,” he added.

One of the main concerns for both artists is what they call the university’s disregard for the protection of the freedom of expression guaranteed to all South Africans under the Constitution.

“The freedom of expression means the freedom of expression. You are free to express. And if you don’t have that, you don’t have freedom of expression,” said Goldblatt. “We do have laws in this country that allow the censoring of work if it’s regarded as being harmful in some particular way.”

Goldblatt insists that the university’s actions differ from the curatorship that takes place in museums around the world. Rather, he says that the administration is blatantly censoring selected works. “It’s different fundamentally [from curatorship] because they did so selectively. They selected certain works. Now, to select certain works is to censor. You cannot do this selectively; either you do this to all of them or none of them.”

He thinks UCT’s actions are dangerous. “At the end of the day, if this kind of attitude persists in the university, what will they do when a group of students come to the archive of photographs and say: ‘You’ve got photos there of Muslims. We’re not prepared to tolerate that. No Muslims, no Jews, or the Anglicans, or people with green eyes’,” said Goldblatt.

“But, if I’m a painter and I choose to show Jacob Zuma with his penis showing, then the question arises – am I to be censored for that?” he asked.

“I strongly urge all South African artists, researchers, recorders of public life etc., and as well those of foreign origin whose products may end up at South African universities, even if inadvertently so, to make absolutely sure your work is not allowed to be acquired, loaned or otherwise used by South African universities,” Breytenbach wrote to GroundUp. “You have no chance of it (the work) being seen for what it is intended to be, no guarantee it will survive the orgies of destruction these institutions foster and no responsibility or accountability (let alone preservation) will be forthcoming from the ethically and aesthetically spineless but oh so glib ‘collaborators’ running the universities.”

UCT reply

We sent UCT the quotes by Goldblatt and Breytenbach and asked for the institution’s response. We were sent the same statement written by Vice-Chancellor Max Price in response to Professor Belinda Bozzoli, previously published on GroundUp.

List submitted to the University by the Artworks Task Team in 2015

The descriptions are by the students who objected to the works. GroundUp has added the artist and title of the work. (All images republished as fair use.)

Oppenheimer Library:

1. Hovering Dog by Breyten Breytenbach (Student description: Portrait of white man with black woman on his lap having sexual intercourse)

2. Saartjie Baartman by Willie Bester

3. A Passerby by Zwelethu Mthethwa (Student description: Black woman sitting on a rock with three children with her all in their underwear in a plastic basin with an impoverished surrounding)

Otto Beit Building:

4. Pasiphaë by Diane Victor (Student description: Portrait of a bull inside it is a black man with his genitals exposed)

Kramer:

5. Dialogue at the Dogwatch by David Brown (Student description: A number of sculptures depicting black men with their genitals exposed)

6. Unknown (Student description: Black people with HIV)

Hoerikwaggo:

7. Similar to the sculptures on the Kramer lawn by David Brown

Chemical Engineering Building:

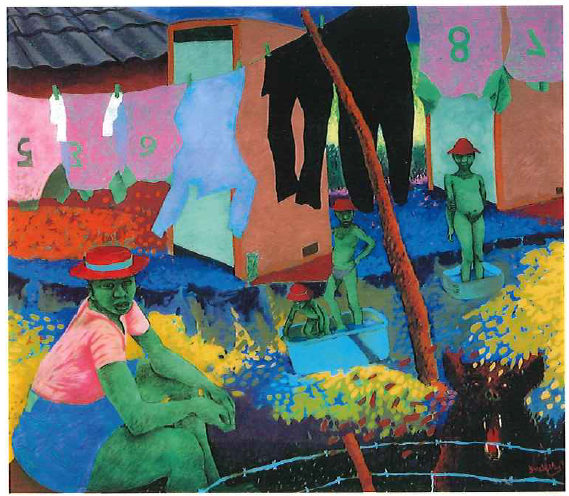

8. A township scene by Vusi Khumalo (Student description: Portrait of poor black people)

EGS Building:

9. Courtyard outside tea room probably by David Brown (Student description: black man with genitals exposed)

Michaelis:

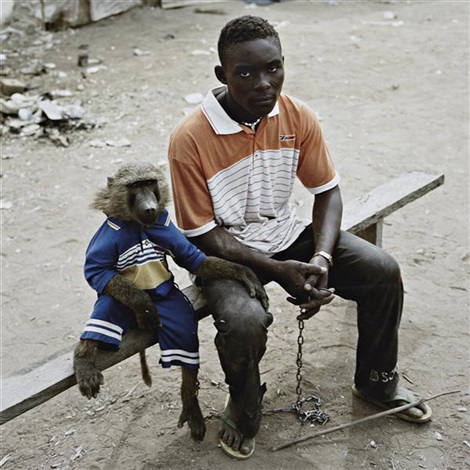

10. Dayaba Usman with the monkey clear, Nigeria by Pieter Hugo. (Student description: Black boy sitting next to a monkey made to replicate the monkey)

List of works destroyed in protests

1. James Eddie, Portrait of Mrs Joan Gie

2. Carli Hare, Portrait of Sue Folb

3. Harriet Fuller Knight, Portrait of Dr Rosemary Exner

4. Edward Roworth, Portrait of Mrs Barnard-Fuller

5. Edward Roworth, Portrait of Mrs Doris Spencer Emmet

6. Edward Roworth, Portrait of Mrs Anna Maria Tugwell

7. Roeleen Ryall, Portrait of Mrs Arlene van der Walt

8. Roeleen Ryall, Portrait of Mrs Rosemary Taylor

9. Rupert Shephard, Portrait of Mrs Marie Lydia Grant

10. Bernard Hailstone, Portrait of Harry Frederick Oppenheimer (1908-2000)

11. Neville Lewis, Portrait of Albert van de Sandt Centlivres (1887-1966)

12. Edward Roworth, Portrait of Jan Christiaan Smuts (1870-1950)

13. John Wheatley, Portrait of Edward, Prince of Wales

14. Richard Keresemose Baholo, Graduation Day

15. Richard Keresemose Baholo, Extinguished Torch of Academic Freedom

16. Richard Keresemose Baholo, Release Our Leaders

17. Richard Keresemose Baholo, Rekindling the torch of Academic Freedom

18. Richard Keresemose Baholo, The girl witch

19. Kirsten Lilford, Intimacy

20. Nina Romm, Twee Jocks and a Lady

21. Robert Broadley, Portrait of Prof Theodore Le Roux

22. Stanley Eppel, Portrait of Prof Owen Lewis

23. John Wheatley, Portrait of Prof Alexander Brown

24. Molly Blackburn Collages (not identified by UCT, but confirmed)

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Letters

Dear Editor

http://www.netwerk24.com/Nuus/Algemeen/kosbare-kunswerke-by-uk-vernietig-20160229

These works were also destroyed: Many important females. The collages of Molly Blackburn were several photos of her, she was from the Black Sash. See the informations below from my article.

n Borsbeeld deur die bekende kunstenaar Delise Reich van die eerste vrou wat aan ’n Suid-Afrikaanse universiteit gestudeer het, Maria Emmeline Barnard Fuller, is ook met verf beskadig.

Fuller het in 1886 onderwys aan die UK se voorloper, die South African College, gestudeer en ’n sleutelrol gespeel in die ontwikkeling van die kampus.

’n Portretstudie van haar is ook verbrand.

Twee unieke foto-collages van Molly Blackburn, ’n bekende lid van die Black Sash-beweging wat onder raaiselagtige omstandighede in 1985 in ’n motorongeluk dood is, is ook verbrand. Volgens History Online was daar 20 000 mense – meestal swart – by haar begrafnis.

’n Ballerina wat internasionale roem verwerf het, Rosemary Taylor, se portret deur Rupert Shepard is ook verwoes.

Fuller se portret (deur Edward Roworth) is ook verbrand, saam met dié van ander vroue, naamlik Doris Spencer Emmett en Anna Maria Tugwell (albei deur Roworth), Joan Gie (James Eddie), Sue Folb (Carli Hare), dr. Rosemary Exner (Harriet Fuller Knight), Arlene van der Walt en Rosemary Taylor (albei deur Roeleen Ryall) en Maria Lydia Grant (Rupert Shepard).

Anna Maria Tugwell was die eerste huismoeder van die eerste koshuis vir vroue by Groote Schuur. Sy het ook aan die South African College gestudeer.

Die ander portrette wat verband is, was van Harry Frederick Oppenheimer (Bernard Hailston), Albert van der Sandt Centlivres (Neville Lewis), Jan Christiaan Smuts (Edward Roworth), prof. Theodore le Roux (Robert Broadley), prof. Owen Lewis (Stanley Eppel), prof. Alexander Brown en Edward, Prins van Wallis (albei deur John Wheatley).

Dan was daar ook die vyf werke van Keresemose Richard Baholo wat in die 1990’s ’n student by die UK se Michaelis-skool vir skone kunste was.

Dear Editor

As I and others have noted before, this appalling and disgraceful censorship by the UCT executive undermines the core values of a university - freedom of speech and expression, and academic freedom. To date, despite repeated requests, and despite claims by the UCT Exec that the full list of censored artworks would be made public, this has not been done. Why the secrecy, one asks? And readers should note that the Saartjie Baartman statue in the Library STILL remains covered up, against the wishes of the artist himself.

What this indicates is that UCT has abandoned the core principles that constitute a university. Despite the harsh criticism from artists, members of the public, and voices within the university, the UCT Exec continues to display a brazen and unrepentant disregard for freedom of expression. This is an utter disgrace, and the UCT Exec should be thoroughly ashamed of itself for capitulating to tyranny. If UCT continues on this path of obsequiousness, it will cease to be a university. This will have terrible implications for the future of both higher education in South Africa, and for the country itself. The short-sighted behaviour of the Executive is staggeringly misguided.

Dear Editor

I think it would be useful to differentiate the removal of the Zwelethu Mthethwa work, from the others removed. Mthethwa's work is seen as very contentious in light of his prison sentencing as announced on Wednesday. The protesters of the "Our Lady" exhibition at the National Gallery dealt with these problematics extensively.

My understanding is that the other works you mention form a group of works which were deemed problematic more broadly in terms of race within the current conversations of transformation and decolonization.

Dear Editor

Concerning the art that was destroyed it is ironic that the borderlines of decency can be crossed by multiples of people. Cognitive dissonance can be induced by subliminal messaging such as humans having sexual intercourse while dogs are looking on or a neatly clothed youngster sitting next to a neatly clothed baboon. That is in fact the same cognitive dissonance when feeling sorry for student's plight while they are performing criminal and derogatory acts of violence and mass-narcissism.

Dear Editor

Destroying works of art, or any form of creative expression, based on the spurious judgments or biases of others is called oppression.

In this case, the oppression of one of our basic human rights, that of freedom of expression. It seems that not much has changed regarding tolerance in South Africa.

We need to remember the French Revolution and Evelyn Hall's statement ' I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it'. If Universities cave on freedom of speech, they may as well burn all art and books, as they'll always be able to find someone who doesn't like something.

Is this what our freedom has come to? People burning works of art? That doesn't take much guts, or intellect.

Dear Editor

With the body politic lurching from crisis to crisis, the economy in recession, and the judiciary groaning under the weight of the hordes of disgruntled/dismissed/out-of-favour senior managers in the SOE’s seeking redress, one might be tempted to dismiss the continuing coverage of UCT’s art censorship as trivial and self-indulgent.

That would be a mistake.

Art, in its diverse forms, constitutes a form of expression. Like speech, it must be respected and allowed to be created and viewed by all who wish so to do. To abrogate or limit that right, especially in a university setting, is nothing but censorship, and needs assiduously to be resisted and “called out” whenever it occurs.

Freedom of expression, and its close relative, academic freedom, are essential pillars of what sustain the very notion of a university.

UCT’s censorship of on-campus art, regardless of the spin that accompanies the act, is nothing but an assault on long-held and critical aspects of what makes a university a university, rather than a technical or vocational college.

Unfortunately, art censorship is but the latest of a long string of actions by UCT’s Executive (with the support of Council) that assail the above-mentioned principles. It appears that UCT’s leadership is in thrall to a small, malevolent gang of individuals whose understanding of, and caring about, academic freedom and freedom of expression (except their own, of course) is minimal if not zero. It further appears that any action taken by the Executive that tramples underfoot fundamental notions of free speech and expression, not to mention the rule of law, is justified by the mantra of “decolonization and transformation”.

There is no justification for censoring art, or, for that matter, removing art from the public domain, regardless of how the removal is justified or characterized. A more responsible response to art that might offend, is to encourage more art. Censorship is a crude and irresponsible act; one that cannot but harm all who call UCT home.

Dear Editor

It is frustrating to watch the established art world whinge about precious artworks lost during student protests, and ultimately, a curatorial process.

This idea that art is a bastion of 'freedom of expression' is steeped in hypocrisy considering that the 'eye of the beholder' is exactly that. 'Freedom of speech' according to whom? 'Destruction of property' according to whom? 'Violent acts' according to whom? 'Censorship' according to whom? If there is anything we should've realised and learned as 'creatives', it is that art is just as susceptible to being institutionalised and co-opted into systems of oppression and exclusion. One person's 'freedom of expression' is another person's form of oppression.

So, yes, student protests are messy and uncontrollable. We were once young too, and those of us with open eyes and awakened conscience burned our own kind of 'shit and stuff' when we were young. When has youth ever been 'neat and clean' in its protest? When has youth ever been 'emotionally mature and experientially wise' in their actions?

Youth is passionate, angry, zealous, idealistic and ready to deliver the full blow of their convictions - to their own, and our, detriment.

So yes, we lost a lot of precious artworks, many of them symbols of our revered 'freedom struggle', 'rainbow nation' and 'Important History'. I'm sure a lot of this detail got lost in the fires of contempt lit by the student protests.

The much more important question to ask, is why this came to be in the first place.

As somebody who spent a decade in the creative education field as an 'industry professional', I've watched on in frustration as academic institutions refuse to wake up and open up to the realities of the crises unfolding around us. I am appalled at the apathy and lack of desperately needed radical transformation in our educational institutions - particularly in the 'creative arts' field and 'professional arts' industry.

Considering the precipice we find ourselves at, it seems unforgivable.

Dear Editor

UCT’s equivocation on freedom of expression is contemptible. Just as Sean Spicer’s spin is quickly undercut by Trump’s tweets, the UCT Marketing Department’s claimed commitment to artistic freedom is contradicted by the Artworks Task Team’s order that paintings, photographs, drawings, and sculptures continue to be censored indefinitely. And Vice-Chancellor Max Price takes refuge in the sophistry that no artworks have been “banned”, when they are unquestionably being censored.

If, as the Artworks Task Team recommends, “some of the contested artworks” are taken out of storage and displayed together “in dedicated spaces such as the CAS Gallery”, comparisons with Goebbels’s Entartete Kunst exhibit will be unavoidable, and the injury done to the artists will be compounded. It would be better to stay out of the censorship business altogether.

UCT used to be made of sturdier stuff. Under apartheid censorship, the UCT library boldly stamped banned literature with the statement:

"BANNED IN SOUTH AFRICA

This notice reminds readers that the University of Cape Town is opposed to the State’s system of censorship, which undermines academic freedom and restricts the potential contribution of this university and others to South African society. The University of Cape Town is required by law to comply with the rules and regulations pertaining to censorship, but does so under protest."

It is disturbing to watch a great liberal institution lose the courage of its convictions.

Dear Editor

Is there an essential difference between Nazi storm-troopers burning books by Jewish and other "undesirable elements", and students burning paintings that they have decided are undesirable? Perhaps so, but if so it is a very small one, as far as I can see. One may dislike symbols of past people and/or events, but one cannot rewrite history. It belongs to all of us, and if we destroy parts of it that we dislike, instead of accepting all of it, warts and all, we destroy part of ourselves. Even worse, we destroy something that belongs to generations yet unborn.

© 2017 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.