Sex offenders in schools: how government botched a crucial learner safety project

In spite of government promises, only one teacher in ten has been screened

Poster design by Nathi Ngubane, with a photo by Ashraf Hendricks for GroundUp.

- Fewer than one in ten teachers have been vetted against the National Register of Sex Offenders, more than a year after the initial deadline.

- Some convicted sex offenders who have been identified in schools, have not been removed from their posts.

- For years, confusion in the education sector meant that no one was doing criminal background checks on incoming teachers.

- The vetting drive remains crippled by non-compliance from teachers and a lack of coordination across government departments.

More than a year after the government’s deadline to remove convicted sex offenders from South Africa’s public schools, a national vetting drive continues to falter. Despite lofty promises, the Department of Basic Education (DBE) has still screened fewer than one in ten teachers and staff at schools against the National Register for Sex Offenders (NRSO).

Internal DBE statistics and an investigation by Viewfinder shows that the vetting process – now years behind schedule – remains crippled by confusion, non-compliance from teachers, and a lack of coordination across government departments. Meanwhile, children remain exposed, as likely scores of convicted sex offenders remain employed at schools.

In provinces where some vetting has occurred, 49 convicted sex offenders have already been identified in schools. In some cases, it appears, they have remained in their posts.

Against this backdrop of failure, Basic Education Minister Siviwe Gwarube incorrectly told Parliament in May that 19% of teachers and school staff had been vetted. In truth, this figure reflected only the number of vetting requests submitted to the NRSO — not completed checks, which lingers at closer to 9%.

If the 49 figure is a representative sample, it would mean upwards of 230 convicted sex offenders were employed at public schools when the vetting drive kicked off in 2022.

Minister of Basic Education Siviwe Gwarube. Photo: GCIS

Government liable

The danger this failure poses is not theoretical. South Africa’s children are at extraordinarily high risk of falling victim to sexual abuse. More than 20,000 child rape and sexual assault cases are reported to the police annually. The education departments in provinces such as the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal, where the incidence of such crimes are high, have reported almost no progress on the vetting drive.

Cases of teachers sexually abusing their pupils regularly make headlines across South Africa.

Viewfinder has further uncovered a serious historical blindspot in the hiring of teachers — one that the vetting drive sought to address. It is likely that the majority of teachers currently employed in public schools were never subjected to criminal background checks when they were originally hired. That means that convicted sex offenders had a clear pathway to employment in schools in many provinces, up until the South African Council of Educators (SACE) made police clearance certificates mandatory for incoming teachers in 2019.

Around the time that the vetting drive got underway in 2022, a case in the Western Cape High Court laid bare the impact that this failure has had in ruining one girl’s life.

Lindy (not her real name), a woman in her twenties, was suing Nolan Swanepoel, the former principal of Vleiplaas Primary School outside Barrydale, for raping her in the school’s bathrooms on an afternoon in September 2011.

She was also suing the province’s education department, because it had hired Swanepoel years earlier without doing a criminal background check. If it had done so, the department would have uncovered that he was previously convicted of the sexual assault of a child.

Lindy, which is not her real name, sits for an interview with Viewfinder and Carte Blanche in February 2025. Photo: video screenshot.

The court found the Western Cape Education Department (WCED) “vicariously liable” for the rape and ordered it and Swanepoel to pay Lindy damages.

“I was a sweet child. But, I have become somebody that I no longer recognise,” said Lindy, during an interview with Viewfinder in February. She still lives with her mother in the farmlands surrounding Vleiplaas Primary.

“He (Swanepoel) threatened me and said that if I told anyone, he would kill me along with my family,” Lindy said.

Asked why she did speak out, she responded:

“Out there are many of us who do not get the chance … who are too scared to stand up for what happened to us. Nobody believes us. But, with one voice perhaps it can become a better place for us.”

Lindy’s case featured on a Carte Blanche segment on the vetting drive produced by Viewfinder in February.

No vetting historically

Nolan Swanepoel’s employment in the early 2000s was not an anomaly. For years, convicted sex offenders across South Africa had a clear path to employment in public schools.

The WCED, according to spokesperson Bronagh Hammond, introduced criminal background checks as a hiring criteria for teachers in 2016 – five years after Lindy’s rape.

Most other provinces likely did not follow suit, according to a survey of queries to the eight other provinces.

Only the Northern Cape said definitively that it had done such checks, before national teacher certification body SACE introduced these as part of its processes in 2019.

Limpopo’s spokesperson Mosebjane Kgaffe confirmed that the department did not vet incoming teachers.

Gauteng’s Steve Mobana said, “No comment from us.”

KwaZulu-Natal’s Muzi Mahlambi said there was no “government directive” for the criminal record of teachers to be checked.

North West’s Mphata Molokwane asked for a query to be emailed, but he did not respond to it and follow-ups.

The Free State’s Howard Ndaba said they were working on a response, but none has been forthcoming.

The Eastern Cape’s Vuyiseka Mboxela said “personnel suitability checks” included “criminal checks”, but appeared to reference a directive not historically applied to teachers.

Mpumalanga’s spokesperson Gerald Sambo said that the department had historically relied on SACE, despite it being clear that SACE was not doing these checks before 2019.

During an interview in February, Enoch Rabotapi, the DBE’s main official charged with coordinating a response to sexual abuse in schools, conceded that, historically, “as a department, we need to admit that not due attention was paid to the issue of vetting”.

“We do have people who have a history of being abusive to children who ended up finding a way into our education system,” he said.

Teachers blamed

The vetting drive began in 2022 with promises from the DBE of a process that appeared straightforward. Teachers would obtain “fingerprint reports” from the police, which would show whether they had prior criminal convictions. Then, teachers were to complete paperwork required for their employers – the nine provincial departments of education – to request NRSO clearance certificates from the Department of Justice in Pretoria.

But, from the start many teachers simply ignored the process. Some cited the confusing paperwork. Others didn’t want to pay the police processing fee out-of-pocket. Some may have feared what a background check would reveal about their criminal pasts.

“Vetting is not a voluntary process,” said Rabotapi.

“Anybody who does not subject themselves to the process will be liable for an offence, and disciplinary action will have to be taken.”

Enoch Rabotapi, the DBE’s Chief Director for National Institute of Curriculum and Professional Development. Photo: DBE on X

But, he conceded that no disciplinary action had at that point, in February, been taken against teachers who refused to comply. The Department did not respond to a question as to whether this has changed.

In reporting, for instance to the Education Labour Relations Council (ELRC), some provincial departments have cited “refusal” and “non-compliance” from teachers as reasons for their dismal progress with vetting.

But, the South African Principals Association (SAPA) has pushed back. In many provinces, principals are the implementers at schools of provincial directives that teachers and school staff be vetted.

“We’ve had to grapple with what these forms are all about. We are not legal people. We are administrators in schools. And so you’ve got to understand, this process is foreign to us,” said Linda Shezi, SAPA general secretary.

“I will be telling a fib if I said that actual process, and how lengthy it can be, was explained to us. No, it wasn’t.”

SAPA president Grant Butler said: “Principals across the country have mailed their provincial departments with questions, but they were very seldom answered.”

Longstanding issues with police remain unresolved

Still, teachers who tried to comply often hit a wall at police stations. Some officers rejected applications, charged inconsistent fees, and did not honour a recently brokered fee waiver. Sometimes the issuing of fingerprint reports were delayed for months.

These were issues raised by Minister Gwarube during a May meeting with Police Minister Senzo Mchunu – itself a follow-up on a December meeting where similar challenges with the police were discussed between the Ministers. The promise of a dedicated joint task team, which emanated from the December meeting, appears to have had little effect.

Bottleneck at Department of Justice

Some provinces have managed to collect completed vetting forms from teachers and send these to the justice department. But there, another crisis awaits.

The justice department, and the NRSO office in particular, is unable to handle the volume. As of May, a backlog of nearly 50,000 applications remained unprocessed. From December to May, the department averaged only around 1,200 NRSO clearances a month.

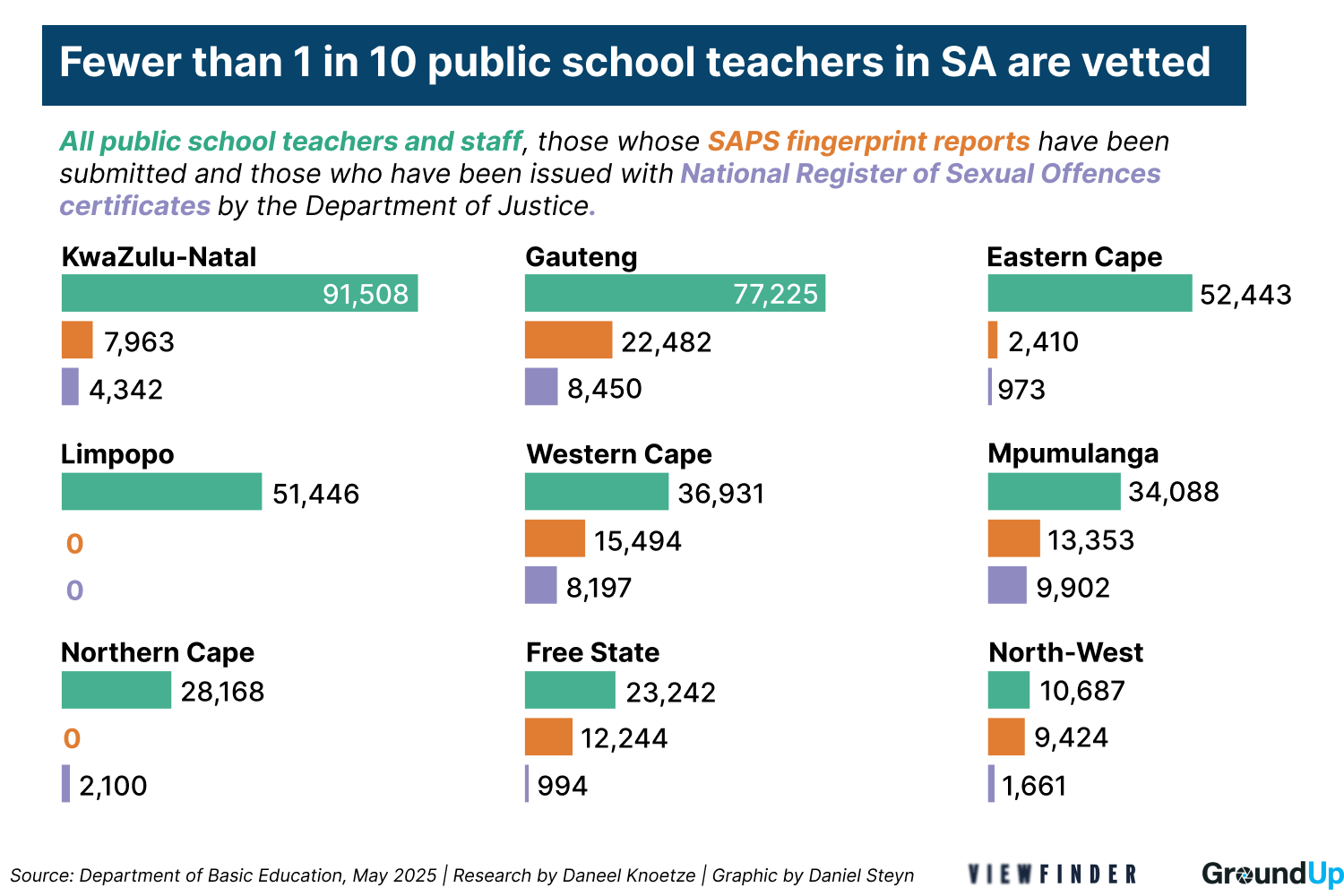

Internal Department of Basic Education statistics, broken down by province, show the extent to which the sex offender vetting drive has failed. The statistics are from May 2025 (Source: DBE)

Justice Minister Mmamoloko Kubayi warned in February: “This inefficiency means that many of our children are at risk of being in the hands of a sex offender.”

She promised to publish the NRSO so that employers could check it directly. But Kubayi has since been forced to walk back that promise due to concerns that publishing the register might contravene privacy laws.

The justice department has blamed staff shortages, power cuts, and outdated systems. It has not delivered on commitments, made in response to queries in December, to clear the backlog.

“The NRSO is labour intensive. If additional human resources can be put in place, the NRSO will be able to turn things around,” said justice department spokesperson Kgalalelo Masibi in response to queries in June.

“The department is in the process of securing additional funds to capacitate provinces with human resources.”

No response from police, education departments or SACE

Viewfinder submitted a substantive query, detailing the facts and findings of this report, to the DBE and Minister Gwarube’s office. Departmental spokesperson Terence Khala acknowledged receipt and said that the query was receiving attention. In the end, the Department did not respond.

Police spokesperson Colonel Athlenda Mathe acknowledged receipt of a query. She did not respond.

SACE spokesman Risuna Nkuna acknowledged receipt of a query about the period before 2019, during which the council was certifying teachers without doing criminal background checks. He committed to respond. He did not respond.

Viewfinder queried the provincial education departments where the 49 convicted sex offender teachers were identified - Gauteng, Free State, Western Cape and Northern Cape. Their spokespeople were asked whether these sex offenders had been removed from schools. None responded.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Police officers protest against rape and sexual harassment in their ranks

Previous: Belal Khaled’s photographs bring the horror of life in Gaza to Johannesburg

© 2025 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.