These are our rights when we use medicines

South African law says that we must be informed about our health care options

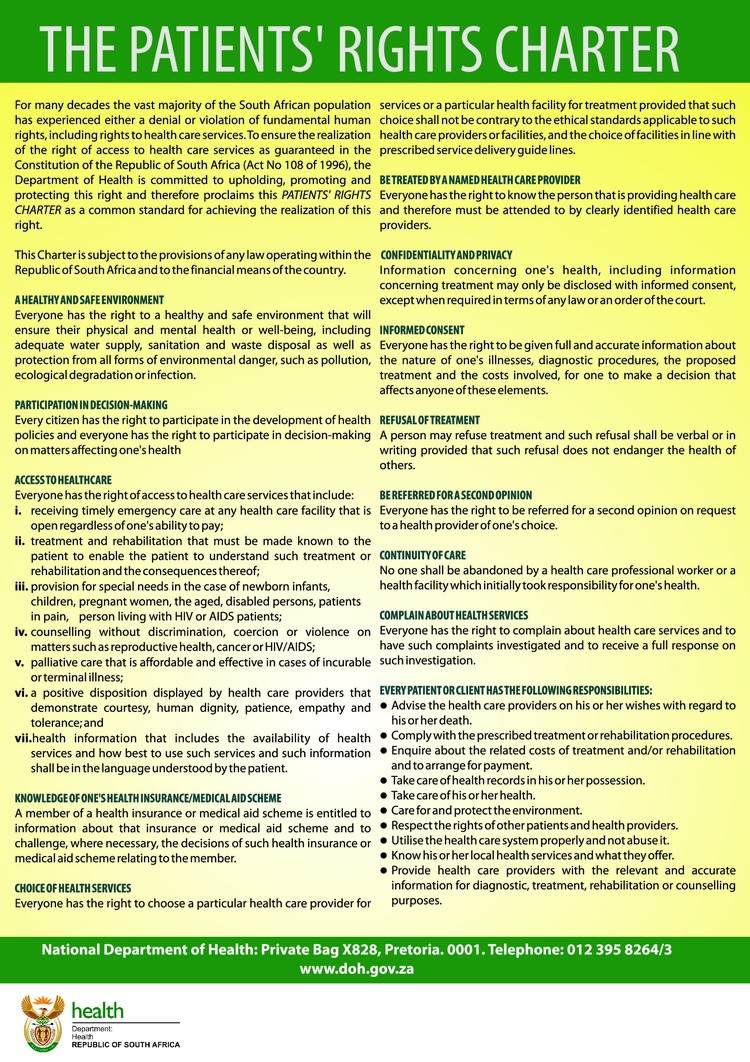

The rights and duties of users and health care providers are clearly described and should be enforceable. In practice there are many barriers in both the public and private sectors. Photo: Giorgos Moutafis, courtesy of Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders).

GroundUp proposed that the right to be informed should be recognised as a human right. The right to be informed is already included in the South African law when it comes to our health. Chapter 2 of the National Health Act 2003, deals with the rights of health care users and duties of health care providers and workers.

Section 6 of the Act is headed: User to have full knowledge.

The law requires:

“every health care provider must inform a user of—

- (a) the user’s health status except in circumstances where there is substantial evidence that the disclosure of the user’s health status would be contrary to the best interests of the user;

- (b) the range of diagnostic procedures and treatment options generally available to the user;

- (c) the benefits, risks, costs and consequences generally associated with each option; and

- (d) the user’s right to refuse health services and explain the implications, risks, obligations of such refusal.”

This information must also be conveyed “in a language that the user understands and in a manner which takes into account the user’s level of literacy”.

The next section requires that a “health care provider must take all reasonable steps to obtain the user’s informed consent”. This means that the user has consented to the treatment or health service.

The point is hammered home in section 8: “A user has the right to participate in any decision affecting his or her personal health and treatment.”

The rights and duties of users and health care providers are clearly described and should be enforceable. In practice there are many barriers in both the public and private sectors. The Patient Rights Charter may well be posted on hospital walls but like the faded Batho Pele posters, it has become merely part of the décor.

You have the right to know about the medicines you take

Medicines should be included in the range of treatment options disclosed to each patient, together with their associated “benefits, risks, costs and consequences”.

Patients, parents and caregivers may also access information about medicines from many other sources, including marketing materials published by the manufacturers and sellers of such medicines.

The Medicine Act’s regulations limit advertising. The only medicines that can be advertised directly to consumers are those containing substances in Schedule 0 (which can be sold in any retail outlet, for example paracetamol, often branded as Panado) and Schedule 1 (which can only be sold in a pharmacy, for example ibuprofen gel).

Medicines containing substances in Schedules 2 (also pharmacist-initiated) and Schedules 3 to 6 (prescription-only medicines) may only be advertised to health care workers and practitioners.

| Schedule | Medicine | Note |

| 0 | Paracetamol (Panado) | But only if 25 tablets or less |

| 1 | Ibuprofen gel | For application to the skin |

| 2 | Ibufprofen tablets | Maximum dose of 1.2g per day and a maximum of 24 tablets |

| 3 | Insulin | |

| 4 | Amoxicillin | This is a penicillin antibiotic |

| 5 | Diazepam (Valium) | |

| 6 | Morphine |

Advertisements may also not include information that differs from the medicine’s approved use.

Every medicine registered by the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) is required to have an approved professional information (PI) as well as a patient information leaflet (PIL).

The PI is written in technical language for professionals, whereas a patient should be able to read the PIL.

In September 2024, the minister issued a proposed amendment to the regulations for comment, allowing the PIL to be printed in English only, but also requiring that it be provided in any of the other official languages in electronic format.

Is the restriction on direct-to-consumer advertising justifiable, and is it effectively enforced? Only the US and New Zealand allow direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription-only medicines.

Restricting advertising of prescription-only medicines is justified on the basis that it reduces inappropriate use of such medicines, influenced by patient demands.

Is this enough?

Does South Africa’s medicine legislation meet the right to be informed?

Patients may want more information, even after being prescribed a medicine. Being verbally informed of the risks and benefits of a medicine by a pharmacist or doctor may not be enough; a patient may need to read the PIL.

The PIL should be accessible in languages other than English, but if these are only available electronically, it might be tricky to access it. A link or QR code included on the packaging of the medicine may make this easier.

Although the SAHPRA website provides a repository of PIs and PILs, it does not restrict access to the former to health professionals only. There are also implementation issues. No approved translations of these documents are accessible, and the resource appears to be incomplete.

Also the existing regulation of advertising is severely limited because it fails to take account of the many other channels by which information is disseminated, including websites and social media. Medicines might be advertised directly to people using these channels. The quality of this information may be poor, or inappropriate for particular patients.

Manufacturers’ websites may include navigation options to consumer and professional versions, but these are difficult to enforce. Those that are provided to a US market are easily accessed outside of that country. Also, where the use of medicines is promoted by influencers on social media, this may well be beyond the reach of existing regulatory systems.

The covid pandemic provided an instructive case study, where many websites and public figures promoted the use of ivermectin for both prevention and treatment, despite the lack of evidence. Misinformation about medicines is reaching the public, despite the law.

While the “right to be informed” certainly applies to medicines, and the rights and duties of users and health care providers are clearly described in law, the reality is that existing attempts to regulate the marketing or promotion of medicines are not enough to protect the public.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Huge admin costs threaten fund for sick miners

Previous: Hundreds of unemployed young people march to Nigel factories for jobs

© 2025 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.