Explainer: HIV, HPV and cervical cancer

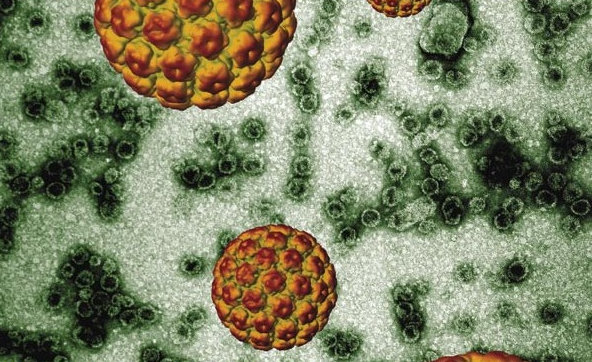

Image of Human Papilloma Virus by Dr Arvind Varsani, Electron Microscope Unit, University of Cape Town (2007). Originally published in Equal Treatment issue 22. Public domain.

South Africa has one of the highest HIV rates in the world, with 8-million people estimated to be living with the virus. While many people are aware of the link between HIV and Tuberculosis (TB), fewer know about another common co-infection: Human Papillomavirus (HPV).

What is HPV?

HPV includes a family of more than 200 viruses – of which about 40 are sexually transmitted.

These strains are divided into low-risk and high-risk types. Low-risk strains are associated with milder conditions, such as genital warts, and in most cases, a healthy immune system can clear the infection without complication. But persistent high-risk HPV infection can lead to cancers, including cervical, anal, and throat cancer.

How are HIV and HPV connected?

The relationship between HIV and HPV is particularly important in South Africa, where millions of HIV-positive people are at risk of HPV-related cancers.

Research by the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute found that 79% of HIV-positive men tested in inner-city Johannesburg had genital HPV infections. A separate study from UCT found that 74% of HIV-positive women were infected with HPV, compared to under 37% of HIV-negative women. When the immune system’s guard is lowered by HIV, opportunistic infections are a lot more likely, and a lot harder to clear.

And the relationship appears to go both ways. A University of KwaZulu-Natal study found that an HPV infection is associated with a 2.5-fold increase in the risk of acquiring HIV. Researchers believe this is because HPV infections trigger inflammation in the genital tract, attracting CD4+ T-cells, which are the very cells that HIV targets. Although the mechanism of this relationship is not yet clear, their increased presence in the genital tract could facilitate HIV entry and infection.

What does HPV have to do with cervical cancer?

HPV is responsible for more than 95% of cervical cancer cases in South Africa. If a high-risk HPV infection persists, it can cause abnormal cell growth in the cervix. Left untreated, this can develop into cervical cancer.

Anna-Lise Williamson, a virologist, an author of the UCT study and leading HPV researcher, explains:

“Cervical cancer is treatable within the pre-cancer stage, but without access to regular screening to catch the cancers, they can become invasive – which can be a real challenge to treat.”

Can HPV and cervical cancer be prevented?

Yes. HPV-related cancers, including cervical cancer, are largely preventable through vaccination and regular screening.

HPV vaccinations protect against the two most common high-risk strains of the virus. In 2014, the South African government introduced an HPV vaccination programme, offering free vaccines to girls in public schools. Although the vaccine is most effective before the age of 15, it is still recommended to get the vaccine if you are under the age of 26.

Should boys also get vaccinated?

Vaccinating young women is a major public health milestone. But boys are also at risk of getting HPV-related cancers and transmitting the virus to their partners. If possible, boys and young men should also get vaccinated.

The bigger picture

Being vaccinated is the most effective way of preventing infection, but for those who are already infected, regular screening is vital for early detection and appropriate treatment – especially for HIV-positive women who are more vulnerable. Yet access to Pap smears and HPV testing is hugely unequal across the country.

Because of its sexually transmitted nature, HPV carries stigma and misconceptions about who is at risk. But the truth is, nearly all sexually active people contract some form of HPV in their lifetime. The core of the issue lies in access to healthcare, rather than in lifestyle choices.

“People always think it’s about different sexual behaviour and networks,” says Williamson. “But it’s really not. It’s about women having access to healthcare and treatment.”

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Patients have to get water brought to them at this Durban hospital

Previous: Trump has stopped aid to South Africa, endangering thousands of lives

© 2025 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.