The human cost of South Africa’s unsecured lending explosion

There are examples in the world of responsible lending to poor people, but not here

As the UN Human Rights Commission zooms in on the threat to human rights posed by the explosion of private debt, we, as South Africans, should do the same.

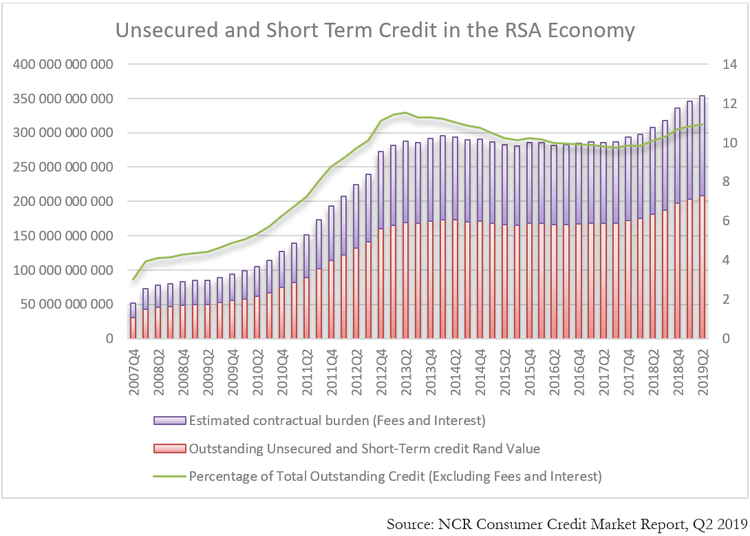

Experts are concerned that the adverse socio-economic impact of unsecured loans — loans which are not backed by an asset such as a house — vastly outweighs the benefits of bringing a historically excluded population into the formal financial sector. These loans may be worth as much as R350 billion.

A recently published report on private debt and human rights, to be presented to the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in March, seeks to focus on the human cost of lending.

By framing the debate within the context of human rights, the UN report questions not whether our lending systems are beneficial to shareholders of banks and financial institutions, but whether they are beneficial to society as a whole.

South Africa’s unsecured lending industry exploded into existence after the promulgation of the National Credit Act in 2007 and has fundamentally altered the composition of the domestic credit market.

Between 2008 and 2011, unsecured and short-term credit to consumers grew by 260% to a peak of R28,3 billion, according to data published by the National Credit Regulator (NCR). Levels declined slightly in 2014 and 2016 but are soaring again.

In the second quarter of 2019, R31 billion worth of unsecured loans was granted to consumers, representing 23% of the total value of all loans granted, and surpassing, in nominal terms, (not taking inflation into account) the peak levels last seen in 2011. This excludes a further R21 billion granted in credit facilities, including credit cards, store cards and bank overdrafts which are defined separately in NCR data. Combined, the two categories represent nearly 40% of all credit issued in the period.

As a result, the year on year growth to the second quarter of 2019 in the value of outstanding unsecured credit in the economy far outstripped all other forms of credit, growing by over 15%.

Today, there is as much as R208 billion in outstanding unsecured and short-term credit in the domestic economy, accounting for 11% of all outstanding credit, according to NCR data.

If fees and interest owed by borrowers are added to the debt, the outstanding value of unsecured loans may be as much as R350 billion, according to a recent analysis by asset managers, Differential Capital.

As near eight million “first-time” borrowers have absorbed hundreds of billions of rands in unsecured credit, the South African domestic credit market has been fundamentally transformed.

But at what cost?

Because unsecured credit and short-term credit are not backed by a form of security, and are typified by high levels of consumer default, these forms of credit tend to be far more expensive than other forms of private credit.

The cost of unsecured and short-term credit ranges anywhere from 37% a year for a 61 to 90 month loan, to 225% for a one month loan, according to Differential Capital. Mortgage finance, by comparison, tends to be charged at around 11% a year.

Good and bad debt

“The question is when is debt good and when is it bad?” asks former banking executive turned investor and shareholder activist, David Woollam.

“Broadly, ‘good debt’ is used to invest in a business, education, or assets such as house, and can be very empowering. ‘Bad debt’ is used for consumption spending and debt recycling and equates to stealing from one’s future income with very little sustainable benefit.”

Woollam believes that more than two thirds of unsecured credit is spent on consumption and on financing debt repayments. Worse still, the values of unsecured loans being used to refinance pre-existing debt have increased to alarming levels.

Differential Capital estimates that a whopping 63% of new unsecured loans are being used to refinance debt, as consumers “borrow from Peter to pay Paul”.

Woollam says Differential’s data shows that the number of new unsecured borrowers has been declining and the industry is increasingly relying on the refinancing of debt by increasing loan terms and amounts to existing clients.

“This game of musical chairs just lures borrowers into bigger and bigger loans and masks the real financial stress these borrowers face”, he says.

Erin Torkelson has shown how social grants were “transformed into collateral for credit and encumbered by debts” by Net1 which was contracted to pay social grants. Social grant recipients formed a very secure market for lenders who nevertheless charged them costs similar to those prescribed for unsecured credit in the National Credit Act.

Extending credit to poor people might be seen as beneficial as it enables a “smoothing over” of household crises. But borrowers are merely postponing the crisis. “The next time borrowers can’t cover their basic needs, they have less money because of the high allowable costs on unsecured credit, like interest, monthly fees and initiation fees. So, they borrow more money from other lenders to cover those costs,” says Torkelson.

Consumers are borrowing from their future to pay, at twice the price, for today’s bread. In this way, lenders “gain ownership of the borrower’s futures by exploiting the desperation of the present,” says Woollam.

It is “mostly an expropriation of workers’ income for the benefit of the rich. The vast majority of consumers in this space are technically insolvent, with few assets and lots of debt, and are having to work harder and harder just to stand still. The headwinds and lack of growth faced by our economy are bound to crack open this uneasy situation at some point in the near future”.

Defaults

Today, a whopping 41% of borrowers are described in NCR data as having an impaired record, an indicator of over-indebtedness. While this is down from peak levels seen in 2014, it is still significantly higher than before the unsecured boom in 2007. As many as 23% of borrowers have an account in default today, compared to 13.5% seen in 2007, according to NCR data.

The recent growth in unsecured lending has regulators nervous, with the South African Reserve Bank ringing early warning bells.

“Of particular concern is the strong increase in unsecured lending to the household sector”, says the bank in its November 2019 Financial Stability Review.

This growth and the high cost of unsecured loans is “likely to weigh on households’ finances and impact the ability to repay debt”. The non-performing loan ratio for the unsecured sector has been ticking upward since 2018, “indicating that the sector may already be facing some difficulty meeting its unsecured debt obligations”.

Debt collections abuse features prominently in the UNHRC report with specific attention afforded to the South African case.

Systemic abuse of poor people has also been a central focus of a number of recent landmark court rulings, with successive judges denouncing lenders’ behaviour while also highlighting the human rights concerns of extractive lending.

In 2015, a ruling handed down by Judge Siraj Desai found excessive charges associated with collections via the notorious Emolument Attachment Order system to have a “direct impact” on a range of constitutionally enshrined legal rights stating that “the ability of people to earn and support themselves and their families is central to the right to human dignity”.

A 2018 ruling by Judge Murray Lowe, read alongside the Desai ruling, ensures that borrowers have collection judgments issued at courts they are able to access. Before these judgments, debt collections attorneys had routinely opted to secure orders against borrowers in courts far from their homes or places of work, and where court clerks were uncritical – a practice known as “forum shopping”.

The Stellenbosch Clinic, along with Summit Financial Partners, then succeeded in a second ground-breaking court victory in December last year when the Cape High Court delivered a damning judgment against credit providers who had overcharged consumers in legal and interest fees. The order should put an end to a wide-spread practice whereby collections attorneys, acting on behalf unsecured lenders, interpreted sections of the NCA designed to limit the amount borrowers can be charged in the collection of debt, in such a way as to exclude legal fees.

In his ruling, Judge Bryan Hack noted a problem of spiralling indebtedness in South Africa despite which consumers are constantly being coerced and cajoled into taking on more debt. “The question is whether … credit providers have shown the responsibility called for to balance the respective rights and responsibilities of credit providers and consumers. The facts of this case suggest no,” said Judge Hack in his judgment.

“There is a ray of sunshine” in terms of SA’s private debt industry, says senior attorney at the Stellenbosch Clinic, Stephan van der Merwe. He argues that in legislation tied to the Constitution and bill of rights there has been a clear intention to protect borrowers from abusive practices. The recent judgments serve to tighten this legislative framework.

In a 2017 report the South African Human Rights Commission found that that over-indebtedness in South Africa “significantly affects an individual’s ability to cover their basic household needs, thereby affecting their access to socio-economic rights”, which has a corollary effect on the right to dignity, as described by Judge Desai.

Further, while “lending schemes may be predominantly targeted at middle-income groups, it is the lower income groups and those in poverty who are rendered the most vulnerable to human rights violations resultant from unethical lending and debt collection practices”, the Commission said.

Inequality

A recent World Bank report on poverty and inequality in South Africa cited high over-indebtedness among lower income consumers as one of the reasons that financial inequality has increased. In terms of net wealth inequality, a shocking 70.9% of the wealth in the country is held by a single 1% of the population. Meanwhile, the bottom 60% of the population enjoy a mere 7% of the country’s wealth.

We have moved “away from a race-based form of inequality seen during apartheid to a market-validated form of inequality,” says Dr Milford Bateman, a leading international critic of theories of microcredit as models for poverty alleviation.

“The same outcome is being achieved, it’s just the method of doing it that has changed”, he says. “Seeing the poor as a commodity that you can pile up with credit as a way to extract value from them is the exact opposite of extending human rights.”

As pointed out by the UNHRC report, household debt is not a problem in itself. “The ability to borrow within the limits of one’s own financial capacity may improve people’s living standards, allowing access to services that would otherwise be out of reach; and it may play a role in activating and supporting the economy.”

There are some “noble causes”, for lending to poor people and there are examples in the world of “responsible lending and responsible spending”, but not in South Africa, says Dr Shane Lavagna-Slater, lecturer at the University of Western Australia.

“The South African unsecured lending market is not sustainable in its current form. To have a sustainable market means having cheaper credit and lower defaults. Currently you have the opposite”, he says.

Over-indebtedness among millions of lower income South African borrowers, compounded by aggressive debt collection, works to entrench inequality and denies poor people the hope of a meaningful participation in the economy.

There is a small but growing call from concerned experts within South Africa’s financial sector not to invest in unsecured lenders. Such experts argue that trustees and others entrusted to safeguard funds under their custody should take action if those funds are invested in unsustainable and ”immoral or abusive or exploitative” business practices. This would be difficult for institutional investors which have seen massive returns from investing in major lenders. Yet, there are early signs that this call is starting to be heard.

As citizens, too, we need to ask whether the profits we make today have come at the expense of the financial futures of poor people.

Views expressed are not necessarily those of GroundUp

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Minister instructs schools to enrol undocumented children

Previous: N2 highway blocked as Butterworth residents protest over water

Letters

Dear Editor

Given South Africa's inadequate levels of education particularly in mathematics and especially among the poor, it is highly questionable whether the concept of “percent” is understood even at a basic level.

I would like to suggest that all lenders are given a schedule separately showing the Rand value of interest and capital for each month of repayment. It should be sub totaled over each 12 month period as well as for the full term of the debt.

The borrower must be shown how much interest is paid in Rands compared to the amount borrowed.

© 2020 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.