Cape Town’s water use remains too high despite Day Zero lessons

The city consumes over a billion litres per day, equating to over 210 litres per person, well above the world average of 120 to 160 litres

Theewaterskloof Dam on 24 April 2018. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

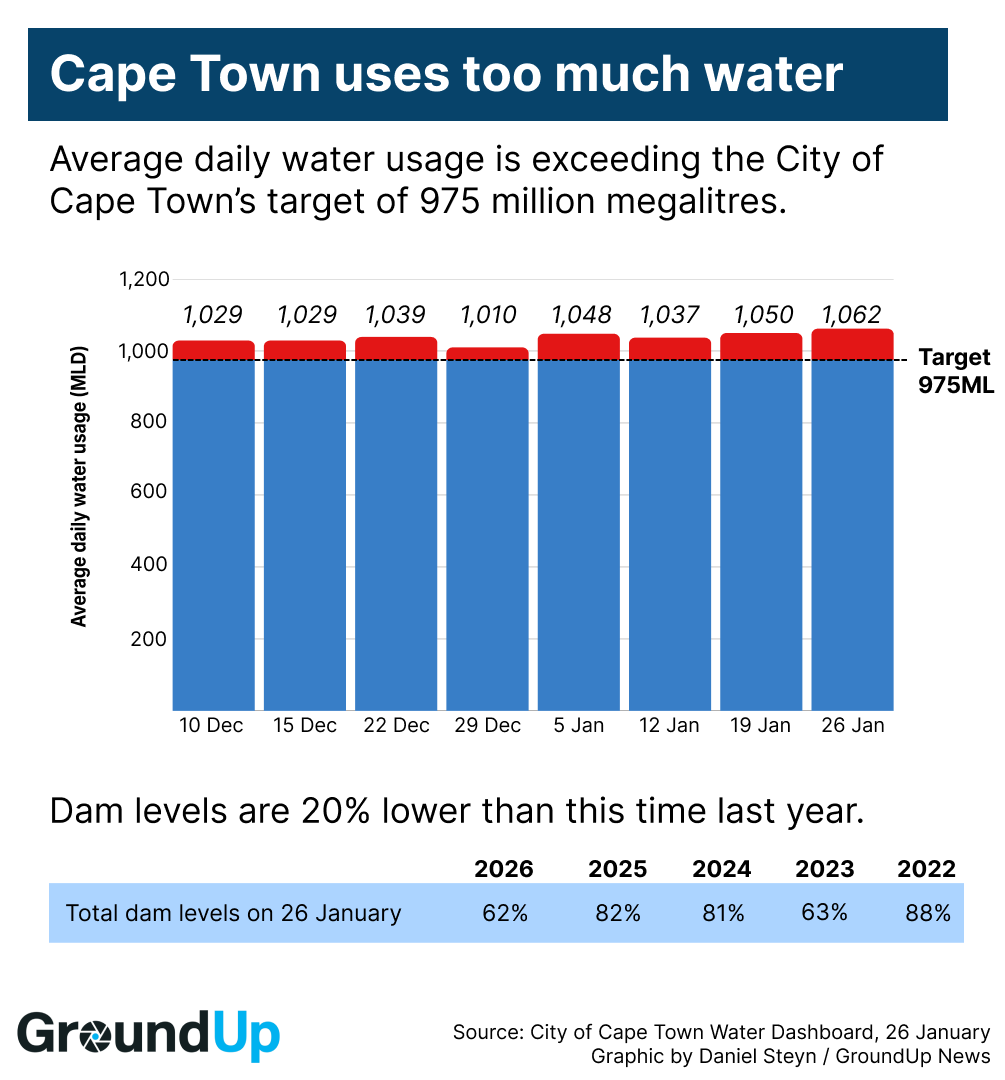

- Cape Town’s population is consuming about 1,056 million litres per day, exceeding the City’s summer target of less than 975 million litres.

- The South African Weather Services predicts below average rainfall.

- The City estimates it loses about 23% of its water through leaks and unaccounted for consumption.

Cape Town’s bulk water managers are not ignoring the warning signs. The near Day Zero crisis of 2018, when dam storage fell near to the critical 13% capacity, has permanently shifted how the municipality manages its water resources.

Now there are models and baseline reference data that should avoid the city getting anywhere near that critical level, when water can no longer be pumped from our dams and treated effectively.

A data-driven model, updated weekly, determines the level of water risk. This data is shared on the municipality’s water dashboard, which is updated at 2pm every Monday.

But information alone does not address water demand, especially during the dry, hot summer months or periods of below-average rainfall.

Furthermore, the six major dams feeding Cape Town do not serve the city alone, but also supply farmers and other towns. The municipality is licensed to abstract about 60% of the available supply, while the rest is allocated to agriculture (33%) and the remainder to smaller towns.

Demand this year is tracking similar to 2023, when the municipality did not impose any restrictions. Fortunately, it rained. By July, the main dams were almost at 100%. But this should not make us complacent. There is no guarantee that we will receive a typical winter rainfall this year.

South African Weather Services predict a below average rainfall. If their models are accurate, we may return to that early warning sign, when water storage was about 39% of capacity in November 2017 and little prospect of rainfall until at least June of the following year.

Climate projections for the Western Cape suggest temperatures will rise by between 1°C and 3°C over the next three decades. Farmers will be on the frontlines of this temperature increase.

Rainfall is harder to predict. Some years, like 2018, which was the same year Cape Town experienced its Day Zero scenario, significant rainfall occurred on three occasions after August. The Berg River even overtopped the dam wall in September 2018.

Usage remains too high

Across the city, water use is too high, and much higher than the average per-person use in cities in Europe and other parts of Africa.

The municipality has set a target of less than 975 million litres per day (MLD) for the summer season. But usage has been consistently above this. Cape Town’s population of approximately five million people is consuming about 1,056 MLD, equating to 212 litres per person per day. The world average is between 120 and 160 litres per day.

Part of the problem is structural. Surface dams lose water through evaporation, especially under hot and windy conditions. Surface water dams are not the most efficient means of storing water, but there is no other viable option currently for Cape Town.

The municipality also estimates it loses about 23% of its water through leaks or unaccounted for water. What the municipality has to do right now is to address the water losses, fix the leaks, and increase the means of collecting revenue from all water users. Revenue is vital to establish and maintain future water resilience and to afford the more expensive options of water desalination and water reuse. These are expensive solutions, but probably the only long-term strategy for sustaining the city.

Cape Town’s population is expected to grow by about a million people over the next ten years. Not only will a rising population need to be supplied, but climate change is set to affect the south Western Cape, making it more drought prone.

We have to reduce consumption, fix losses, and invest now — before we face another Day Zero scenario.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Nigel pensioners unable to pay municipal arrears

Previous: “Gangster” municipality fails to pay pension fund contributions

Letters

Dear Editor

Impose restrictions now, whilst we still have water. Check all the complexes watering during 9am to 6pm times, washing of bins after refuse collection and using portable water.

Dear Editor

We have the sea, endless water and the funds to build many desalination plants, just duplicate those who have the intelligence and backbone to get up off the bench's of parliament and do something.

Dear Editor

Why are there no alternate water storage or sources other than dams?

Cape Town city learned nothing from 2018

Now average ratepayers have to reduce their water consumption even more.

Not good enough!

© 2026 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.