Right to protest is under sustained attack

Equal Education’s recently concluded sleep-in protests in three cities have shown how disturbingly difficult it has become to hold legal protests, even for organisations fortunate enough to have access to resources and legal expertise.

Last week EE demonstrated in Cape Town, Pretoria and King William’s Town. Each protest took the form of a ‘sleep-in’, a non-violent occupation outside a government building. The purpose was to force the Minister of Education, Angie Motshekga, to publicly disclose the 9 provincial plans for implementing the new Minimum Norms and Standards for School Infrastructure. The Minister has had the plans since November 2014 but has ignored EE’s multiple letters and its Provision of Access to Information Act (PAIA) request, while her officials have repeatedly made vague assurances that the plans will be released soon.

It is proving hard to get the school infrastructure implementation plans. But laying our hands on permits to demonstrate for these plans was almost as difficult.

The Gatherings Act regulates protests. However both ANC and DA governments are proving increasingly adept at extracting every stifling possibility from this 1993 law. And they often go beyond it.

In Pretoria a last-minute e-mail from the City of Tshwane denied permission on the grounds that “the sidewalk … is for the use of pedestrians” and “no person is allowed to carry on any business or cause any obstruction”.

The venue chosen in Cape Town was outside Parliament, near where Louis Botha rides his horse. EE organisers submitted the required notice to the city’s Public Participation Unit, which reports to City Manager Achmat Ebrahim. This was done, as the Act recommends, more than seven days prior to the protest. It gave notice that 100 EE members would picket and sleep outside Parliament’s gates from 1 – 3 April.

The law requires that any negotiations the authorities want to conduct should be arranged within 24 hours of receiving notice of a protest. Nothing was heard from the City until 3:20pm on Monday 30 March, two days before the planned sleep-in. EE was invited to attend a meeting at the Civic Centre the following afternoon, less than 24 hours before the demonstration was due to begin.

Adv Irwin Robson chaired the meeting, attended by EE, city officials, traffic officers, the police, and Isak David of the Parliament Protection Services. SAPS was represented by Captain Andre de Graaf of the Public Order Policing Unit, which last month shot stun grenades and rubber bullets at high school students.

Citing the National Key Points Act, De Graaf and Robson insisted that no permit could be issued without the approval of the Speaker of Parliament. City officials later explained that since the EFF’s disruption of the State of the Nation Address, all protests to Parliament require the permission of the Speaker.

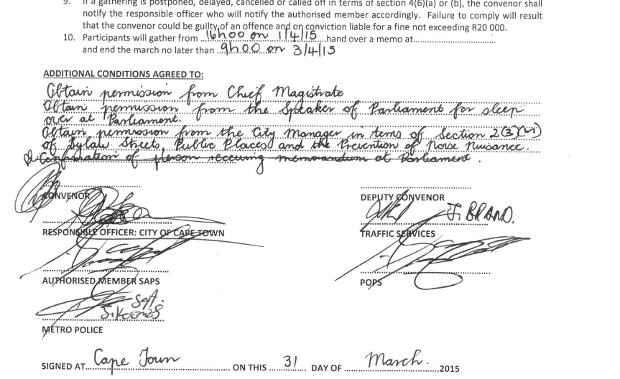

Robson, on behalf of the City of Cape Town, initially refused to issue a permit for the gathering. He instead instructed a city official to review all of EE’s gathering permits over the past five years, and adjourned the meeting. When the meeting reconvened Robson agreed to a conditional permit, provided permission was also granted by the Chief Magistrate of Cape Town, the City Manager, and the Speaker of Parliament. In violation of the Act, Robson failed to provide written reasons for his refusal to issue an unconditional permit.

Conditions stipulated for Equal Education march. Image supplied by the author.

In fact, the Speaker has no power to approve or deny marches to Parliament, under the National Key Points Act or any other law. This absurdity echoed events in 2010, when EE was refused a permit to march to the Union Buildings without the permission of the Presidency. Then too the threat of an urgent High Court application was required. By what logic of democracy would the target of a protest have the right to prevent that protest occurring?

Similarly, Robson stipulated that the permit was conditional upon government agreeing to receive EE’s memorandum. This he eventually crossed out.

The Act does require the additional permission of the Chief Magistrate of Cape Town for marches to Parliament. But in dozens of marches to Parliament EE has never before had this condition enforced on it.

After the Civic Centre meeting the EE Law Centre began preparing an urgent application to have the High Court confirm the Speaker’s lack of authority over protests. Meanwhile the City Manager, the Chief Magistrate and the Speaker’s office each insisted that they could issue approval only after one of the others granted it first, creating an endless circle. Finally, hours before the sleep-in was due to begin, the Speaker’s office gave verbal approval, noting that its jurisdiction ended at Parliament’s gates. This prompted formal approval from the Chief Magistrate and averted legal proceedings.

This was not the first time that Robson and de Graaf had put unlawful obstacles in the way of EE’s constitutionally guaranteed right, “peacefully and unarmed, to assemble, to demonstrate, to picket and to present petitions”. In 2012 EE drafted urgent court papers when, on the basis of an affidavit prepared by de Graaf, which EE was never shown, permission was denied for a Human Rights Day march in Khayelitsha. The threat of litigation ensured that it went ahead, but this again begs the question of how communities and organisations without immediate access to legal representation are supposed to protest lawfully.

EE too has been forced into holding unlawful demonstrations. Last year students’ right to protest in Maluti, near the Eastern Cape’s border with Lesotho, was denied on purely political grounds. A bizarre 17-person panel that included representatives of the South African Democratic Teachers Union (SADTU) refused to issue a permit. EE went ahead in defiance of this blatant illegality.

There has been a change. An administrative process for providing permits has became a mechanism of political control.

Even under the present Gatherings Act, product of an Apartheid parliament, a demonstration cannot be prohibited unless the authorities are “on reasonable grounds convinced” based on “credible information on oath” that there is a threat of “serious disruption of vehicular or pedestrian traffic, injury … or extensive damage to property, and that the Police and the traffic officers … will not be able to contain this threat”. But officials routinely behave as if denying the right to protest is within their complete discretion.

Legal expert Mandla Seleoane has argued that to address this abuse the Act must be rewritten:

“The Act seems to suggest that you require the permission of somebody to host a gathering in public, but in my view that permission is already granted by the Constitution… We know the Constitution does not protect hate speech. We know the Constitution does not protect people who march with arms. We know it does not protect violent protest… So what should happen, what the Act should do, is regulate how protests happen rather than stipulating that someone has the authority to allow or disallow [them].”

Instead there is a crackdown on protests across the country. Research at the University of Johannesburg reports 43 people killed in demonstrations between 2004 and 2014, excluding the 37 miners murdered at Marikana.

In 2008, Captain de Graaf was accused of deploying rubber bullets and stun grenades against municipal workers. In 2014 he played a leading role in the brutal eviction at Lwandle, where his choice of violence over mediation was described by the former chairperson of Parliament’s Portfolio Committee on Police Annelize van Wyk as “indefensible”.

After ten activists of the Social Justice Coalition were convicted on the charge of convening an illegal gathering earlier this year, the organisation vowed to challenge the constitutionality of the Gatherings Act. This holds out the hope that a spotlight will be shone not just on the law but on the dishonest and dangerous way it is implemented.

It is fundamentally wrong that bureaucrats and police are used to mediate what is essentially political conflict between communities and authorities, brought about by poor service delivery, corruption and widening inequality. But for now De Graaf, Robson and company continue to hold sway over the right to demonstrate.

Doron Isaacs is Deputy General Secretary of Equal Education. Views expressed in this article are not necessarily those of GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.