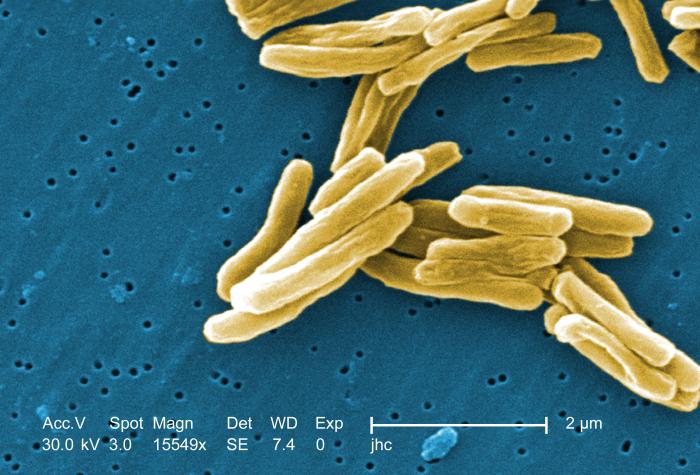

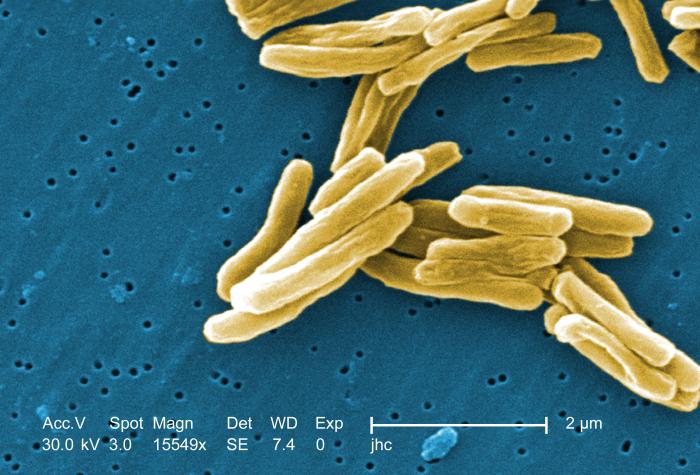

Many, perhaps most, South Africans are infected with TB, but only about 1 in 10 of us will become sick. The image above is from a scanning electron microscope of TB bacteria. Photo: Janice Haney Carr via CDC (public domain)

22 May 2018

In the final article of our three-part series on TB, we look at why so many South Africans are still getting sick with TB.

There were an estimated 430,000 new active TB infections in South Africa in 2016, about one in every 125 people. Worldwide, about 10.4 million people became infected.

Doctors talk about two kinds of TB. With latent TB you have the TB bacterium in your lungs but you don’t have any symptoms and you are not infectious. You are not sick and your immune system has kept the bacteria under control. It is estimated that worldwide in 2014 there were about 1.7 billion people infected with latent TB. It is not known how many South Africans have latent TB, but it could be as high as 80%.

Active TB is the disease. This is when people are infectious and sick. Typical symptoms are coughing that goes on for weeks, chest pains or coughing up blood or mucus.

Only about one in ten people with latent TB become sick with active TB in their lives. But some people are at greater risk. If you have HIV, diabetes, malnourishment, smoke cigarettes or drink large amounts of alcohol, you are at greater risk of latent TB becoming active.

One way to prevent latent TB from developing into active TB is to give HIV-positive people TB drugs to prevent them from developing TB.

South Africa has guidelines that say that all HIV-positive people are eligible for TB prevention therapy. This is called Isoniazid Preventive Therapy (IPT).

It is recommended that IPT be carried out for six or nine months. That’s a lengthy treatment for someone who isn’t experiencing any TB symptoms and the side-effects can be unpleasant.

Dr Sean Wasserman emphasises, “It does work.” It substantially reduces your risk of active TB. But Wasserman points out that as soon as you stop taking IPT, your risk increases again.

But another recent study has shown that a month-long combination of two TB drugs (isoniazid and rifapentine) may be just as effective as the nine month long treatment.

But it’s very expensive, which could mean that South Africa may have to wait a while until it is available.

There are tens of thousands of people who are walking around with active TB and have never been tested. They may not even know they are sick. More people walking around with active TB who are not on treatment, means more people being exposed to the TB bacteria. That’s one reason why it’s vital to find and treat everyone with TB.

A lot of people with TB don’t have symptoms especially if they have HIV, Wasserman explained. It is estimated that about 60% of people with TB in South Africa are also HIV-positive.

One way to combat this is by health care workers actively trying to find people with TB. But going door-to-door and testing for TB can open up a host of ethical concerns such as confidentiality and making sure people can get post-test counselling if needed.

It also requires spending on human resources. But a study in 2014 showed that it can work and it is cost-effective.

Dr Helen Cox, an epidemiologist at UCT’s Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine, told GroundUp that active case finding isn’t done extensively in South Africa, apart from some programmes in mines and prisons.

One reason for this, says Cox, is that we don’t have a really good test to go out with and use on people who don’t have symptoms.

Another good way to prevent the spread of TB is to screen the people who have been in close contact with a person with active TB. These people are at much higher risk of having TB than the general population.

This is important, said Cox, as it doesn’t require new tests. This would also be much more cost-effective than wide-scale case finding, because it targets people who are at particularly high risk of TB.

Wasserman agrees, citing studies that showed that by following up the contacts of someone with TB, many TB cases are found. “I think contact tracing is becoming a really important intervention,” said Wasserman.

Spotlight, a publication monitoring South Africa’s response to TB and HIV, said most experts agree that the government must invest much more in active case finding and contact tracing.

“But unfortunately government has not shown much ambition in this regard. This lack of ambition is probably because government does not want to employ more people,” according to Spotlight.

TB can be prevented by good infection control in public spaces.

Transmission of TB “is just ongoing” in South Africa, said Wasserman. He said some of the reasons for this include the high rates of HIV, the living conditions of many South Africans and poor infection control. “It’s a socio-economic problem. It’s an infrastructure problem. It’s more than a medical issue,” said Wasserman.

A 2015 study that looked at over 130 primary healthcare facilities in South Africa found that primary healthcare workers were contracting TB at a rate of more than double that of the general population.

The Treatment Action Campaign’s survey in March found that 145 of the 207 clinics it assessed had very poor infection control.

“Our clinics should be places we feel safe, where we know we can get decent healthcare services. They certainly should not be places we can get TB,” said Sibongile Tshabalala, the Treatment Action Campaign’s national chairperson, when the results were released.

Cox said that one problem is that often it is only the TB clinic itself that is the focus of infection control. “The reality is, that it’s all areas of health care services [that need to be looked at]. It’s universal infection control. It’s in the waiting room; it’s in the pharmacy; it’s in diabetes clinics and even the maternal and child care clinics, and particularly in emergency,” said Cox.

We still have a long way to go in our efforts to prevent TB, with an assessment in the South African Medical Journal finding that “prevention of TB has been a neglected aspect of TB control”. The authors believe that monitoring health care facilities for infection control adherence, strengthening case finding, and a bigger focus on TB prevention for people living with HIV are some of the changes that need to be made to have a substantial impact on TB control.

The Department of Health did not respond to multiple requests for comment.