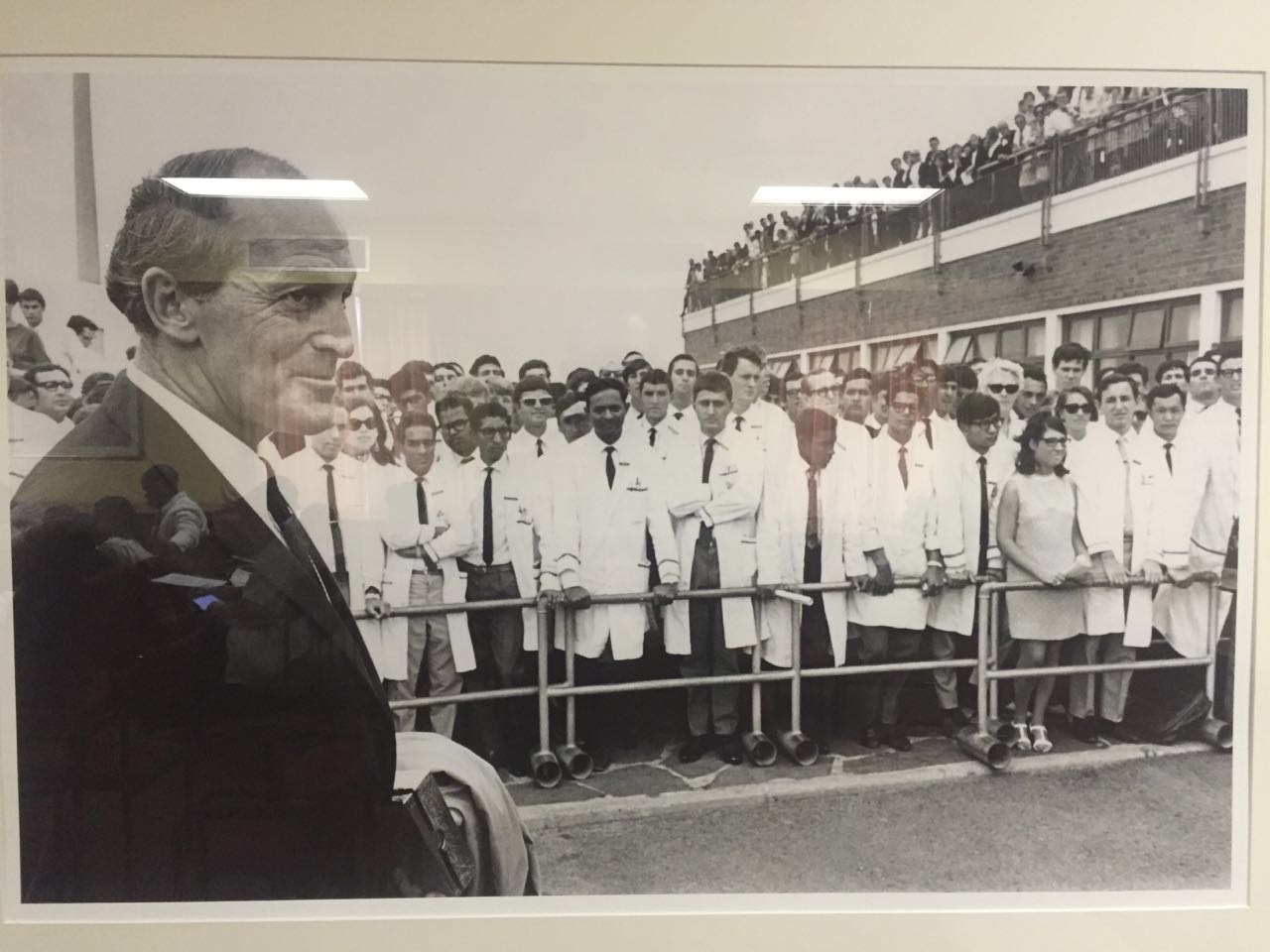

This is a photo of a photo in the Bill Hoffenberg room in Groote Schuur Hospital. It shows Hoffenberg walking to an airplane on the day he went into exile, with many people in white coats standing on the tarmac in support of him.

19 May 2016

White South Africans must recognise that they are the beneficiaries of a monstrous system which created inequalities that still persist, advocate Geoff Budlender argued in his Grey Foundation Memorial lecture in honour of banned UCT academic Bill Hoffenberg. This is an edited version of his speech.

So what do we learn from the life and work of Bill Hoffenberg?

Bill came from the generation which formed the backbone of the fight against Nazism and fascism. We tend to forget that too quickly. It was a generation of people who literally placed themselves in the firing line, who literally placed their lives at risk in the cause of freedom. They did not have to fight: they chose to fight, because the world was at war, and freedom was at stake.

Today we tend to take their courage for granted.

Bill showed a different sort of courage in opposing apartheid. He did not take up arms – but he did what he thought was right, and he was prepared to face the consequences.

I doubt that he saw himself as a courageous person: he did what was decent and what was right.

Bill believed in integrity, and he sought to live a life of integrity, even though this had a cost. That is the most important reason for us to honour him – and if we want to draw lessons from his life, that must surely be the most important.

What other lessons do we draw from his life? One way of trying to understand this is to reflect on the “then and now” – what concerned him then, and where we are now.

It is now 50 years since the Defence and Aid Fund (which Bill chaired) was banned (see Who was Bill Hoffenberg? below).

In 1966, there were 1,310 people serving jail time for political offences, after having been tried and convicted. There were a further 125 people detained without trial under what was called the 180-day detention law.

Today those political offences are gone, and detention without trial is prohibited under the Constitution. We have freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of association, freedom of assembly. We South Africans have become a very noisy bunch.

University apartheid is now over - but many of the former ‘white’ universities are struggling to come to terms with their past, because the past does live on in the present. Some students see their symbols and culture as celebrating a noxious past. A struggle is taking place, and a necessary struggle, but it is often not a pretty sight.

One of Bill Hoffenberg’s prime concerns was inequality. This is what he said, talking about the contrast between those who were well off (almost exclusively white) and those who worked for them (almost exclusively black): “The contrast between our living conditions and theirs was immense but I never stopped to think about it; I took our relationship for granted and never thought it unjust or inhumane.”

There is debate about what is the best way to measure social inequality, but there is no debate at all about the fact that we are one of the most unequal societies in the world.

We need to bear in mind that this inequality is part of our inheritance. It often seems to me that apartheid was like a building: the apartheid laws created a scaffolding for the building when it was being erected – but when the scaffolding was removed after 1994 through the repeal of the apartheid laws, of course the building did not fall down.

Education tells the story perhaps more starkly than anything else. I pulled out some of the education statistics from 1966:

The expenditure on each white pupil was 4.7 times the expenditure on the education of each coloured or Indian pupil;

The expenditure on each white pupil was ten times the expenditure on the education of each African pupil.

Just think of the inequality that alone created.

Actually, those numbers mask the full extent of the inequality. There was free and compulsory school education only for white children. Many children who were not white did not go to school, or did so only briefly. If you look at state expenditure on school education per head of population, as opposed to per pupil in school, the figures are even more stark:

The average for whites was R74.30;

For Indians it was R26.83;

For coloureds it was R17.71;

For Africans it was R2.39.

In other words, the per capita state expenditure on school education for Africans was just over 3.2% of the per capita expenditure on school education for whites.

That ratio gradually improved over the years, although it never even began to approximate equality – that was never the goal. But think of the inequality created by the unequal funding in 1966. Most of those schoolchildren of 1966, and all of their children, are of working age today. Those inequalities are inevitably passed from generation to generation, because our educational opportunities are so heavily shaped by what happens in our homes as we grow up.

That’s an inequality which was hardwired into our society, and into South Africans. Even if our school system were today functioning effectively, that would not eliminate the generational and multi-generational inequality which we have inherited.

Some of the relevant facts today about our public schools are the following. We have 23,740 public schools. Of those:

There are 3,767 schools which have no electricity supply at all, or an unreliable electricity supply;

There are 5,228 schools which have no water supply at all, or an unreliable water supply;

There are 10,419 schools which still use pit latrine toilets;

There are 15,984 schools which do not have computer centres;

There are 20,312 schools which do not have laboratory facilities; and

There are 18,150 schools which do not have access to any form of library.

Overwhelmingly, it is black children who are taught under these conditions. Many things have changed. The apartheid laws are gone. Millions of people now receive social grants, and many millions have obtained access to housing, water or electricity which they previously did not have.

There are many causes of our problems. We need to confront corruption, patronage and ineptitude wherever we see it. But we have to face the fact that much of what we see today is the result of what existed in 1966, and before and after that. We have to face it and deal with it.

Those of us who have been privileged need to show a little humility, and a little empathy. It’s not a matter of walking around stricken and paralysed by guilt. It’s a matter of facing and acknowledging the fact that whether we asked for it or not, those of our generation who are white have been the beneficiaries of a monstrous system which created inequalities which persist today. Once we have acknowledged it, we can start to deal with it. Inequality creates anger, and denialism fuels the anger.

What has this to do with Bill Hoffenberg, and with us? His friend Jonty Driver tells us that Bill Hoffenberg believed in an “egalitarian but pluralist and tolerant democracy”. We won’t achieve that unless we speak up, and act, wherever we see injustice, and whoever is the perpetrator. But when we do so, let’s also remember where we come from, and what a long journey we still have to travel in order to deal with its consequences.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.

Bill Hoffenberg was born and went to school in Port Elizabeth. His studies at the University of Cape Town were interrupted when he enlisted at 18 (by forging his father’s signature) and served in the South African army in World War II as a stretcher-bearer. After the war he qualified as a doctor, and then embarked on a career as a clinician, a researcher and a lecturer. His area of interest was endocrinology.

He joined the Liberal Party, and in 1963, he and a psychologist at UCT, Professor Kurt Danziger, led a petition against detention in solitary confinement, which they declared was a form of torture. In 1965 he accepted the position of chair of the Defence and Aid Fund, which raised money to provide a free legal defence for those who were prosecuted for political offences, and also to provide financial support to the family members of prisoners. It achieved about an 80% acquittal rate for those whom it assisted. The Fund was declared an unlawful organisation in 1966 and Hoffenberg was banned in 1967, the 683rd person to be condemned to this self-imprisonment.

He left SA on an exit permit in 1968, and worked in the UK where he was elected President of the Royal College of Physicians, later becoming President of Wolfson College at Oxford University, President of the International Society for Endocrinology, the British Heart Foundation, and the Medical Campaign against Nuclear War and receiving honorary fellowships from eight colleges and academies throughout the world; and honorary doctorates from four universities.

He was particularly close to the family of Oliver Tambo, the President of the ANC in exile. When Steve Biko was assaulted in solitary confinement, and shamefully treated by those whose job it was to care for him, Hoffenberg raised funds to support a successful court challenge to the failure of the SA Medical and Dental Council to take disciplinary proceedings against those responsible.

Hoffenberg died in 2007, at the age of 84.