Residents facing eviction from the Steenvilla social housing complex erected burning barricades in July. All photos: Ashraf Hendricks

5 December 2017

Burning rubble blocked Military Road, a major throughway in Cape Town’s south peninsula, in July. Tensions over evictions taking place at Steenvilla, the city’s largest social housing complex, boiled over. Sohco, the non-profit company that manages Steenvilla, was trying to evict residents, some of whom were more than a year in arrears in their rent. But a group of residents protested in response, preventing the eviction from taking place.

Offering rented accommodation instead of RDP houses that people own is one important way that the government helps low-income families have homes. Steenvilla’s households earn between R3,800 and R13,000 a month. Because their rents are heavily subsidised, they pay between R1,000 and R3,150 monthly depending on their income, far less than they would pay for equivalent privately rented property in Cape Town.

The system mostly works well. There are over 700 families living in Steenvilla, and only a few dozen have defaulted regularly on their rent since the complex started in 2010. But what happens when people in social housing can no longer afford to pay the rent?

In June this year, the Constitutional Court ruled that judges must ensure that no eviction will leave a person homeless. This was after the court heard the case of 184 residents of a block of flats in Berea, Johannesburg, who faced eviction in 2013. Some had lived there for more than 26 years. The residents had agreed to the eviction, but without properly understanding their rights. The court found that because the residents did not properly understand their rights, their eviction was invalid.

Before the Constitution was adopted, housing rights were governed by common law. This allowed landowners to evict occupiers if they did not have permission to occupy the land (for instance if the lease became invalid). Courts did not take into account why occupiers were on the land, or whether they had alternative arrangements if they were evicted. This approach to property law made it far easier under apartheid for predominantly white landowners to push black people off valuable land.

Things changed in 1996 when the Constitution was adopted. Section 26 of the Bill of Rights, which deals with housing, gives far more protection to unlawful occupiers of land. For example, no one may be evicted from his or her home without a court order and without taking all relevant circumstances into account.

A few years later, the Prevention of Illegal Eviction from and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act of 1998 (the PIE Act) was passed and gave power to Section 26, by requiring that an eviction must be “just and equitable”.

Louise Du Plessis deals with land and housing at Lawyers for Human Rights. “The precedent has been created mostly through the Constitutional Court that there must be alternative accommodation before an eviction order can be executed or granted, and that alternative accommodation must be provided by the municipality,” she says.

But how do these laws play out in real life? And how might they work in the context of evictions at Steenvilla?

Steenvilla is a collaboration between the Western Cape departments of Local Government and Human Settlements, the City of Cape Town, and Sohco.

According to Sohco’s CEO, Heather Maxwell, 31 households out of 700 refused to pay rent, some for over 12 months. After lengthy negotiations with the defaulting tenants, Sohco approached the courts to obtain an eviction order, which was granted.

Convicted armed-robber-turned-politician Gayton McKenzie was reported to have paid R100,000 towards the Steenvilla residents’ legal fees. The leader of the Patriotic Alliance was reported in Die Son to have said: “Even if I have to give R1 million, I’ll give it. Even if I have to get the best advocates, I will get them. Nobody helps the brown people.”

McKenzie has not yet responded to GroundUp’s request for comment.

At the heart of this battle is rent. As Maxwell explains: “The financial sustainability of social housing programmes depends on rentals being paid. The security of tenure of paying tenants is placed at risk by households who do not pay rent.”

A group of residents calling themselves the Steenvilla Housing Action Group mobilised to fight the evictions. They claim that Sohco unfairly hiked rents, which made the block unaffordable. Sohco denies this claim, with Maxwell stating that rents have increased at an average of 7% per year. She says this is far lower than average increases elsewhere in Cape Town which are closer to 12% year-on-year.

“Bring the damn rental down and we’ll all live in peace,” says Tina Schoor, a leader of the Steenvilla Housing Action Group. “Don’t do it for our sake, do it for the sake of the children.”

Schoor alleges corruption and mismanagement at Sohco’s Cape Town and Durban housing projects, and claims that the organisation is motivated by profit. But when asked for evidence of these allegations she responds: “We can prove what we are stating, and there will come a time when we will hand over everything we are stating to the right people.”

“Sohco needs to go because Heather Maxwell speaks a lot of damn nonsense,” says Schoor. “Ask her to show you proof that we can pay.”

“I cannot divulge any individual’s personal information that we are privy to because we have a confidentiality requirement,” says Maxwell in a telephone interview to GroundUp, “but what I can say is that many of the people facing eviction do have sources of income and have been and are still in the position to pay rent, and are in fact choosing not to.”

“The High Court did look at the personal circumstances of the people who were up for eviction,” she says, “and the court at the end of the day did not require the City to provide alternative housing.”

When approached for a follow-up interview to verify some of the claims she made, Schoor said: “I don’t want to do any interviews with GroundUp. I decline all interviews. Please do not contact me.”

According to Du Plessis, if people are in a position to pay, the court “will most likely find that there’s no need for the municipality to provide accommodation”. She says the court would be likely to give people the opportunity to find alternative accommodation.

“If they can’t pay then the duty will be on the municipality to find alternative accommodation.”

“The problem is, what does that alternative accommodation entail?” says Du Plessis. “Unfortunately the law has developed in such a way that at this stage if the municipalities can provide the most basic kind of accommodation like a temporary shelter with basic services, the court has found that good enough.”

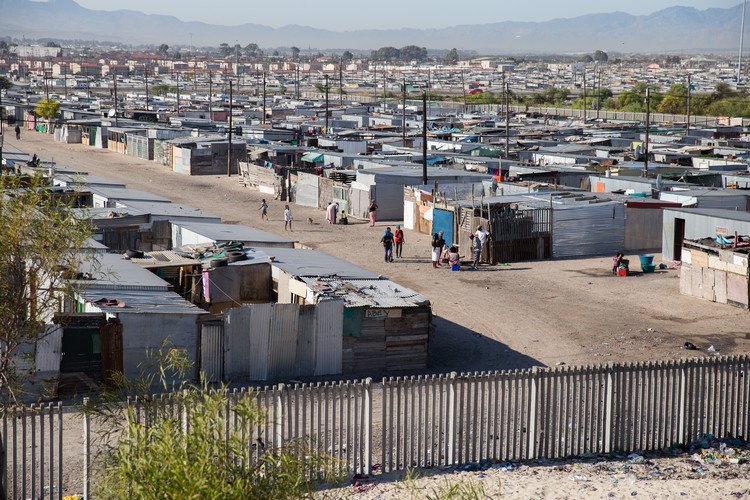

At the moment, “good enough” for the City of Cape Town is Wolwerivier, a temporary relocation area described by many of its own residents as a concentration camp. Wolwerivier is 25km north of Cape Town’s city centre, far from public transport and work opportunities, and is already affected by crime and other social ills.

Another area currently favoured by the City for relocation is Blikkiesdorp in Delft. It consists of corrugated iron shacks plagued by gangsterism, drug abuse and high levels of crime. Both Blikkiesdorp and Wolwerivier have been in the spotlight recently as potential relocation areas for people evicted from Salt River and Woodstock.

City Mayco Member for Transport and Urban Development, Brett Herron, has stated that both Wolwerivier and Blikkiesdorp will be phased out in the coming years, to be replaced by other low-cost housing options closer to the city. But this is still many years off, with a promise of closing down Blikkiesdorp in 2021.

On 23 November, members of the Red Ants evicted the defaulting Steenvilla tenants from the housing project. There was an angry response. A car was burnt and the gates to the complex were broken. A journalist was also attacked during the protests. “Don’t you see our tears? Don’t you feel our pain?” shouted one resident.

In a surprising development, late in the afternoon after the evictions were completed, a man who has not yet been identified arrived at Steenvilla with court papers that ordered a stay of execution of the evictions. They were handed over to SAPS on scene. The Red Ants were told to leave and some of the evicted residents moved back in.

A week later, on 29 November, another High Court order was issued that set aside the 23 November order with costs in Sohco’s favour. The judge was scathing about the conduct of the evictees’ legal counsel and gave the lawyers until Friday to motivate why they should not personally bear the costs of the latest round of litigation and why they should not be hauled in front of the Cape Law Society and Cape Bar Council to explain their conduct.

The story is still unfolding, and another round of evictions to remove the tenants who moved back in is imminent.