7 September 2023

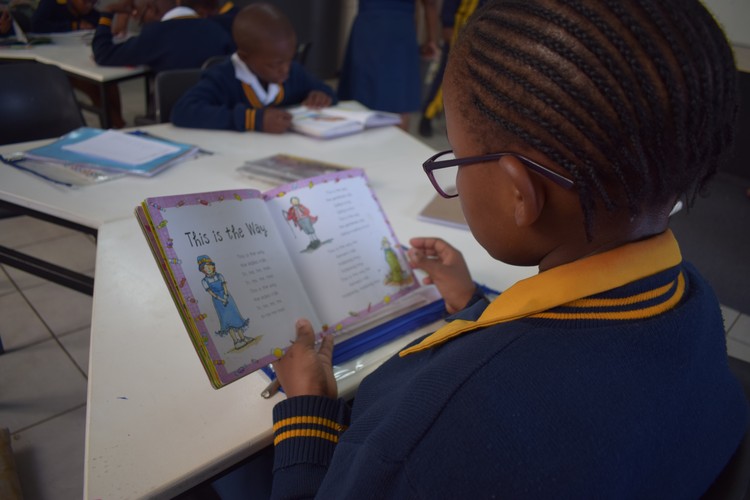

The promulgation of new regulations would help tackle the reading crisis, says the author. But law reform is not enough. Archive photo: Lucas Nowicki

On 30 August, the Right to Read campaign was launched at the Women’s Jail in Johannesburg. The campaign brings together several organisations, including the Legal Resources Centre, the Centre for Child Law, SECTION27, Equal Education (EE), and Equal Education Law Centre (EELC) to mobilise civil society to make early-grade literacy a national priority. But the road ahead will be hard.

The campaign launch comes a few months after the shocking results of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) were released, revealing that 81% of Grade 4 learners in South Africa cannot read for meaning in any language, including their home language. As we mark International Literacy Day on Friday 8 September, we must soberly reflect on the action required to end the national reading crisis.

One of the core strategies of the Right to Read campaign is to motivate for binding reading regulations. These regulations would clarify the state’s obligations in relation to the ‘four T’s’: the time that must be spent on teaching literacy; the training that all foundation phase teachers must receive to ensure they are equipped to teach children to read; the texts that must be provided to teachers and learners; and the regular testing of learners to gauge their ability to read for meaning.

At the EELC, we recognise that law reform is necessary and important. Reading regulations would bring together law and policy and make crystal clear the state’s obligations in relation to reading. Equally, however, we know that law is just one tool in the activist arsenal. Experience shows that good laws on their own are not enough. Time and again, we have seen Herculean efforts made to secure laws that – at least in principle – protect and advance different aspects of the right to basic education. But people are let down when it comes to the implementation of those laws.

An example is the continuing failure of the Department of Basic Education (DBE) to meet the norms and standards for school infrastructure.

Since it was formed in 2008, Equal Education has been campaigning to #FixOurSchools. On 29 November 2013, norms and standards for school infrastructure were finally promulgated. The norms and standards were a victory, in that they set minimum requirements for things like classroom and class sizes and included deadlines for the DBE to meet.

Among other things, the norms and standards required that all public schools must have libraries within ten years: in other words, by 29 November 2023. Yet, EE’s research shows that 70% of public schools still do not have libraries. In addition, a third of school libraries are not stocked. This means four out of five public schools either have no library, or a library without books. The deadline for provision of libraries looms large. It is another deadline that education departments are poised to miss.

The attitude of the DBE towards its legal obligation to provide libraries is disturbing.

On 1 June, not long after the PIRLS results were released, the Minister for Basic Education held a meeting with civil society. She spoke about the results, their causes, and the actions the DBE plans to take in response. She also invited questions from participants.

The EELC took this opportunity to ask whether and how the DBE will be meeting its 2023 deadline for the provision of libraries in schools.

The Minister’s response was astonishing. She appeared unaware that the norms and standards require that all public schools have libraries before the end of the year. And she said this in any event is not going to happen. Her comments make it very clear that laws are not, on their own, enough to secure state action.

What do we at the EELC think this means for the Right to Read campaign?

First, it means recognising that new reading regulations would just be one piece of the puzzle. We must implement what we already have. When public schools have overcrowded classrooms, no libraries, and no books, how can you expect a child to be able to read? The norms and standards for school infrastructure place legal obligations on the DBE to remedy this situation. The DBE must be held accountable for failing to meet those obligations.

We must also recognise that the regulatory framework for basic education already covers teacher qualifications, the curriculum, testing, and more. So the content of reading regulations will to be carefully crafted, to ensure that the regulations add value and do not create new inconsistencies or confusions. Done right, reading regulations have the potential to bring coherence and clarity to the fragmented law and policy landscape.

Second, communities must be central in the development and implementation of the regulations. This means that the content regulations must be developed alongside affected communities – particularly learners, parents, grandparents, caregivers, and teachers at quintile 1 to 3 schools, which are mostly made up of previously disadvantaged schools.

And if and when reading regulations are promulgated, people must be empowered with knowledge and understanding of their content. What do the regulations mean in concrete terms? What are people’s entitlements?

A key part of the EELC’s model is creating and sharing popular education materials. This will be essential to ensure that the DBE is held accountable, and the regulations translate into meaningful and community-driven change on the ground.

Third, we must acknowledge and support other efforts to realise the right to read, over and above laws and their implementation.

To give just one example, in 2010, EE established the Bookery in Cape Town. The Bookery is now an independent sister organisation to EE. It takes donations of books suitable for either primary or secondary school learners and distributes them to schools committed to establishing a library.

There are countless more initiatives to further the right to read – initiatives which were started, and which can make gains, despite the problems with the legal framework. In campaigning for regulations, we must not overlook the continuing importance of these initiatives.

Good laws – while necessary and important – are not enough. To end the reading crisis, we will need to muster all our resources.