6 November 2024

Map: Lotte Manicom/Surefire Communications

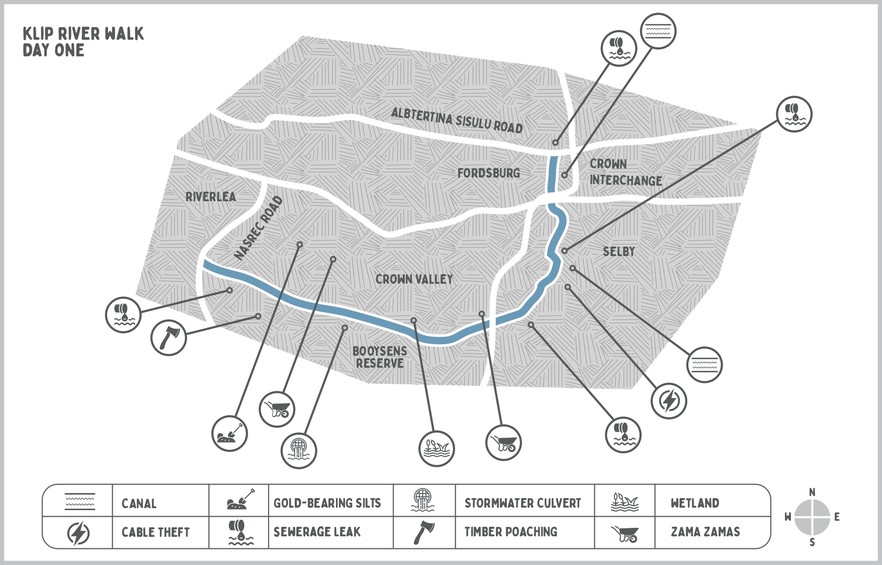

As the magnitude of Johannesburg’s water crisis becomes clear, water authorities are beginning to look at what it would take to use water from alternative sources, including the water running in Joburg’s own rivers. To gauge the feasibility of this, GroundUp took a three day walk along Johannesburg’s Klip River. On the first day, our guides were Andrew Barker, development consultant and Chairperson of KlipSA (Klipriviersberg Sustainability Association) and Johannes Khoele, Head of Security for iProp (formerly Rand Mine Properties).

This article is part of a three-part series.

Part one: Gold dust and gunk

Part two: Boerboels and cable thieves

Part three: A very old church and a mermaid

The Klip River has many sources. One is a stream that begins under the roads and buildings of Newtown at the southern end of the city centre, emerging above ground next to Albertina Sisulu road where Fordsburg meets Selby. In this amnesiac city (Johannesburg’s archives have been variously lost, destroyed, disordered) the name of the stream has been all but forgotten.

The Klip River rises in the stormwater drains under the streets of Johannesburg. Photo: Sean Christie

City authorities refer merely to the Robinson Canal, the concrete channel in which the water flows. In a few surviving accounts from Johannesburg’s first decade, reference is made to the Fordspruit, a stream running out of Fordsburg – this is almost certainly the same stream. On some old mine maps, it is referred to as the Russell Stream, or Russell’s Stream.

This would be the start of our walk. It should have been possible, at the end of a rainless winter, to walk inside the canal, along the elevated edges, but milky brown water filled the invert from wall to wall.

“Very little of that is river water, it’s mostly treated water that has leaked out of Johannesburg’s pipes,” said Andrew Barker. This was no exaggeration. The water loss from Johannesburg’s water reticulation systems, referred to as non-revenue water, is approaching 50%.

Barker added, “We go to all of the trouble and expense of treating water and pumping it uphill from the Vaal Dam, only to lose half of it through broken pipes and reservoirs. Here it is returning to the Vaal in the Klip, completely fouled. A nice round-trip, ultimately paid for by me and thee.”

The quality of the water running in the spruit is probably as bad as it has ever been, but it has been pretty bad for quite some time. Historian Charles van Onselen noted that the Amawasha of the early 20th century — the Zulu washermen who laundered the clothes of the city’s white population — used the Fordspruit and other city streams. The entrepreneurial spirit of the Amawasha notwithstanding, the washing pits were appalling mires, from which “a mixture of decomposing soap and mud” would emit “a constant stream of foul-smelling gas bubbles”.

Even before this, during the great drought of 1895, the spruit appears to have been in trouble, with one account describing how people “for who even a drought was an insufficient excuse for not taking a bath,” would walk to a pool in nearby Booysen’s Reserve to bathe “in evil-smelling water, filled with leeches and abounding in snakes”. As this was a Sunday activity, the bathers were nicknamed the “Sadducees”, and the pool came to be called “The Pool of Siloam”.

Before the discovery of gold in 1886, the area south of Johannesburg was associated with water. There were dozens of springs, streams, wetlands and aquifers, but in time many of these water sources have been paved over, canalised, lost, or forgotten. Photo: Sean Christie

We followed the canal on a well-trodden path, and soon came to a camp of zinc and plyboard shacks. Some of the residents came out and asked to be considered for jobs, mistaking our reflective jackets for official attire. “We have no work here,” one man complained.

The De Villiers Graaff Motorway embankment rose in front of us, its golden sands deeply fissured by water run-off. From the top, Barker, a city planner by profession, explained how the landscape to the south of Johannesburg has changed over time.

“Before there was a city here, this area was notable for its wetlands and spruits. After gold was discovered in 1886, several mines were established in these river valleys. Stream courses were altered, dams were built and in some cases mine dumps were sited in wetlands. The area’s hydrology became increasingly hidden and anonymous,” said Barker, who added that in recent decades it is the historical mining infrastructure – “the shaft openings and the headgears, the head offices and the company golf courses” - that have been disappearing, as mining areas are rehabilitated and developed.

The streams that come together to form the Klip River are heavily polluted with sewage, industrial waste and refuse. A University of Johannesburg study found 4,000 types of microorganisms (many deadly) in water samples from the Bosmont Spruit, which enters the Klip River near Orlando. Photo: Johannes Khoele

We crossed 12 lanes of Crown Interchange traffic and descended on the other side to a small homestead surrounded by freeways and mine dumps. Johannes Khoele, in his 70s but still running marathons, warned us to watch out for dogs: “SAPS [police] doesn’t even know this place exists, so the people here look after themselves,” he said.

Barker had a good name for anonymous slips of land like this: “City planners call it SLOAP – space left over after planning.”

The canal was broader now, so we climbed in and entered the horseshoe-shaped mouths of the tunnels that go under the Pat Mbatha bus lane. Inside, the water deepened until it seemed it would go over the tops of our gumboots. A chunk of Styrofoam was turning in a vortex, presumably created by a sinkhole. It sucked in and popped up again, sucked in and popped up, like something being tugged from below by a powerful animal. We hastily climbed out on the far side, next to a cascading spill of sewage.

“I’m telling you, no eyes have seen this place in years,” said Khoele, documenting the scene with his phone.

It was easier walking beside the bus lane. We passed the derelict Robinson sub-station. On our left, an electricity pylon was missing one of its legs.

“Taken off with a handheld grinder, all for a loaf of bread,” said Khoele, taking a picture. A mix of plastics and organic junk had backed up behind a weir in the canal, forming a floating carpet that stretched for hundreds of metres. Beyond this the stream went down some falls into stacked pillows of stinking foam.

GroundUp noted the neglect of water infrastructure along the upper reaches of the Klip River. Photo: Johannes Khoele

We hopped back into the canal and entered the squashed segmental tunnel that goes under the Soweto-Westgate railway line, emerging in Ophirton Industria, where outflow pipes from some of the workshops had dribbled blue and red paint down the stone canal walls. There must have been a Tipu tree growing nearby because orangey-yellow blossoms lay among tyres, bricks and other features of the canal-bottom.

We came to the convergence point of the Robinson and the Kliprivier Drive canals, and the combined strength of the two streams pressed our gumboots in. Under Spring Street we went, over Lake Street, and continued our walk through a copse of invasive Toon.

Stretches of the Robinson Canal are unexpectedly beautiful, like the section that leads out of Ophirton Industria. Photo: Sean Christie

The canal looped us back to the De Villiers Graaff motorway, where the mouth of the canal tunnel was blocked by netted tree branches. We again scaled the embankment, crossing to the other side between speeding cars.

In front of us the stream, now free of the canal, ran alongside a large area of open land, extending about a kilometre down to Crownwood road. The ground had been flayed by excavators, and tipper trucks were criss-crossing it, depositing loads of wet mud in rows.

Zimbabwean gold panners use the headwaters of the Klip River to sluice gold-bearing silts from a nearby mining site. Photo: Sean Christie

Barker explained that the area is known as the Crown Valley, so-called because Crown Mines’ No.5 Shaft and processing plant had been located here, on the edge of a large wetland. Years of dust from the crushing action of the plant’s stamps had buried the wetland under metres of gold-bearing silt, and it is this valuable soil that is now being scraped up and carted off for processing on behalf of Ergo mines, as part of larger silt removal initiative called the Valley Silts Project.

“It’s a bit like gold panning, on an industrial scale,” Barker said.

The Valley Silts Project seeks to excavate and process gold-bearing silts from the river valleys south of Johannesburg, which have become clotted with gold-rich silt in the course of a century of intensive gold mining. Photo: Sean Christie

To cross the worksite, we had to navigate between pools ringed with orange and white salts. Rubber pipes running out of these fed water, under the power of generators, to gold concentrating tables further up slope.

“Zama Zamas,” said Khoele, not without distaste. The (illegal) artisanal miners were taking their soil directly from the mining company’s silt mounds, and it was all happening in the full view of the drivers of the dump trucks.

Khoele said, “They leave each other alone. In fact, you could say they co-operate – some syndicates are allowed to work in the area, on the understanding that they keep other syndicates out.”

From Crownwood bridge, the view downstream was one of dense bush.

“Let’s take the road,” said Khoele, and for the next 30 minutes we walked the hard shoulder of the Soweto Highway, tracking a line of half-fallen street light columns, all missing their luminaires.

“This city is eating itself,” he said, leading us back into the river valley, following a jeep track through a wood of eucalyptus.

Ahead of us on the road was a bakkie, parked next to a dam that had once served as the water source for the old Bricko factory and quarry. Three men with axes in their hands stood around it. The area around their vehicle was a mess of wood chips and trampled grass.

“I’ve told you not to collect here,” Khoele bawled, bearing down on the men with his camera, taking pictures of their faces and the vehicle’s plates. He explained that the men were in the business of supplying pizza restaurants all over Johannesburg with wood.

Artisanal miners (often referred to as Zama Zamas) operate co-operatively alongside large-scale mining companies in the river valleys south of Johannesburg. Photo: Johannes Khoele

We continued along the jeep track but found that our feet were sticking in the sandy soil. One of Khoele’s gumboots sucked clean off.

It wasn’t sewage, or a water leak, and it wasn’t a spring. Khoele sighed and snapped some pictures of the porridge-like pools that had formed in the road.

“It’s vegetable oil,” he said, and pointed upslope at a series of parked tanker trucks on the property of Gauteng Oil and Cake Mill. We hopped between pools of yellow and white gunk all the way to the edge of Nasrec Road, where Khoele declared, “This is as far as our property goes, and this is as far as I go.” He sat on the culvert, removed his gumboots, and called one of his employees to come and pick him up.

On the other side of the road, seemingly built into the yellow slopes of a slimes dam, was Riverlea.

“If you’re going to experience any major problems, it will probably be on this section,” said Khoele.