4 December 2024

Overcrowding causes inhumane conditions for prisoners, which also impacts prison officials and society at large. Illustration: Lisa Nelson

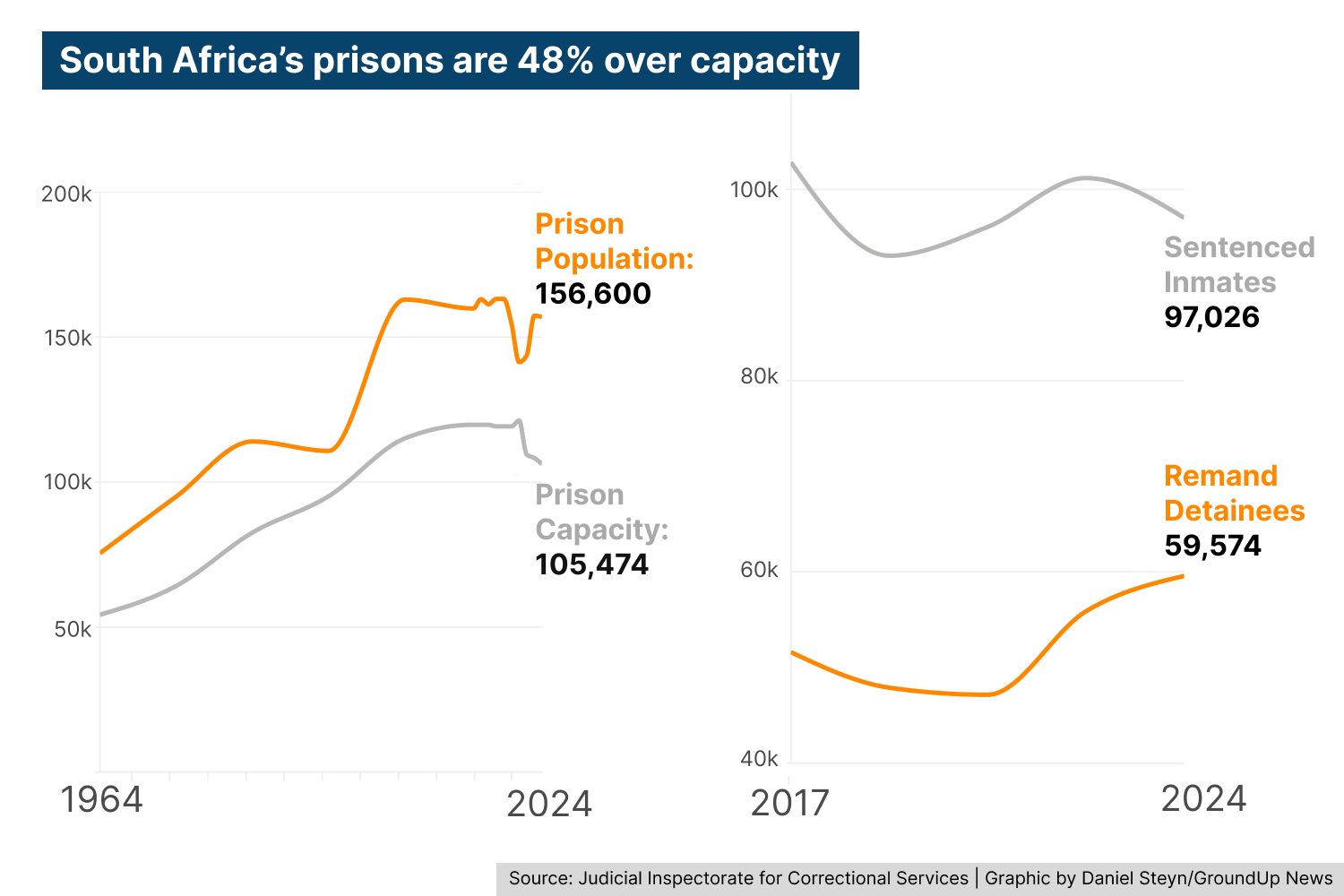

South Africa has about 50,000 more prisoners than our prisons have beds to accommodate them. Our prisons have been overcrowded since at least the 1960s, and yet there is no end in sight: the country’s prison budget is shrinking and there is no substantial plan to build more prisons.

The Department of Correctional Services says others in the criminal justice system, such as the courts, bear the responsibility of reducing overcrowding.

Prison overcrowding causes inhumane conditions for prisoners and breeds violence and crime. This, in turn, impacts the wellbeing of prison warders and the effectiveness of rehabilitation programmes. When prisons are overcrowded, infrastructure is put under tremendous strain, leading to the degradation of facilities. Overcrowding also aggravates the spread of infectious diseases like tuberculosis.

In its most recent annual report, the Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services noted how overcrowded facilities are often volatile and dangerous environments for inmates and staff, and sometimes even controlled by criminal networks and gangs.

Special remissions between 2019 and 2023 saw the sentenced prisoner population decrease, but the number of detainees awaiting trial or sentencing is on the rise. Graphic: Daniel Steyn

For more than a decade, the prison population has remained relatively stable and between 2019 and 2023, the number of sentenced inmates has declined due to several special remissions, which saw tens of thousands of people released on parole. But for the past three years, the number of remand detainees (people awaiting trial or sentencing) has been rising by about 8,000 people a year.

At the same time, a few thousand prison beds have been taken out of commission for necessary upgrades and renovations. This has caused overcrowding to reach 48% in March this year.

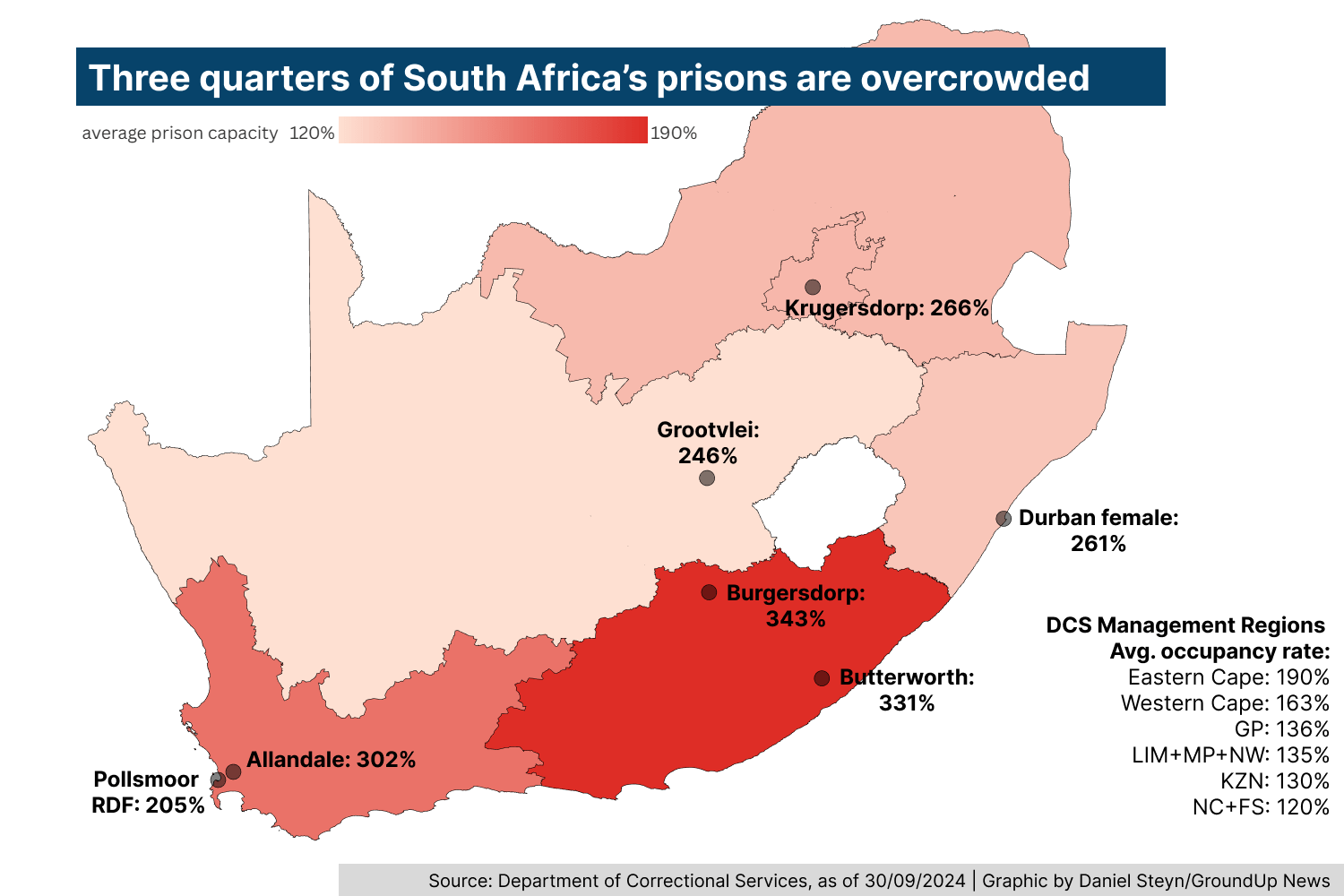

The Eastern Cape and Western Cape have the worst overcrowding rates in the country. This map highlights seven of the most overcrowded prisons in the country. Graphic: Daniel Steyn.

Of the 243 prisons in South Africa, 190 are at over 100% capacity, Minister of Correctional Services Pieter Groenewald recently revealed in Parliament. Overcrowding is not evenly spread across the country. The Eastern Cape has the worst average overcrowding rate of 190%. Remand detention facilities such as Pollsmoor are especially overcrowded.

The Department of Correctional Services says it has been working to move prisoners to less crowded facilities. But this will not solve the problem. According to the latest occupancy figures, there are currently just over 4,000 prison beds not being used, far short of the 50,000 beds needed to solve overcrowding.

Prisoners are usually kept close to where they live, so moving them to other facilities is difficult. Groenewald also said in Parliament that it is not possible to move remand detainees to other facilities, as they have to be close to the courts where their bail hearings, trials or sentencing procedures are taking place.

The Department of Correctional Services faces a decreasing budget over the next three years when adjusted for inflation. The department is battling an infrastructure backlog. (Nominal budget = actual budget amounts, not adjusted for inflation). Graphic: Daniel Steyn

The Department of Correctional Services has no choice but to house everyone the courts order to be detained, yet it is not planning to build new prisons to accommodate all of them.

Prison infrastructure is supposed to be maintained by the Department of Public Works, but dysfunction in that department has caused years of underspending on the prison infrastructure budget. Between 2018 and 2021, the Department of Correctional Services only spent between 40% and 47% of its infrastructure budget. As a result, the department is dealing with a backlog in maintaining the existing infrastructure.

However, budget spending has been improving: in 2021 and 2023, it spent 98.34% and 105.97% respectively.

But the department does not have enough money to build new prisons.

Over the past five years, the department’s overall budget has been decreasing in real terms (adjusted for inflation) and will continue to do so for the next three years. The department’s infrastructure budget was cut massively between 2023 and 2024 and will continue to decrease in real terms until 2026.

The Department of Correctional Services says that the solution to prison overcrowding lies with other roleplayers in the criminal justice system, such as the courts. The remand detainee population is too high due to court delays, the department says.

But Prof Lukas Muntingh, director of the University of the Western Cape’s Dullah Omar Institute, warns that the high number of remand detainees should not be used as an excuse for the department not to build more prison space.

If the criminal justice system were to become more effective, this would lead to an increase in the prison population, not a decline, Muntingh says. “A dysfunctional criminal justice system is saving us from an overcrowding crisis,” he says.

Violent crime, such as murder, has been increasing, yet the prison population has remained stable. Only 10% of arrests result in convictions. This suggests that if the justice system (police, prosecutors and courts) get their act together, more prison space will be urgently needed, says Muntingh.

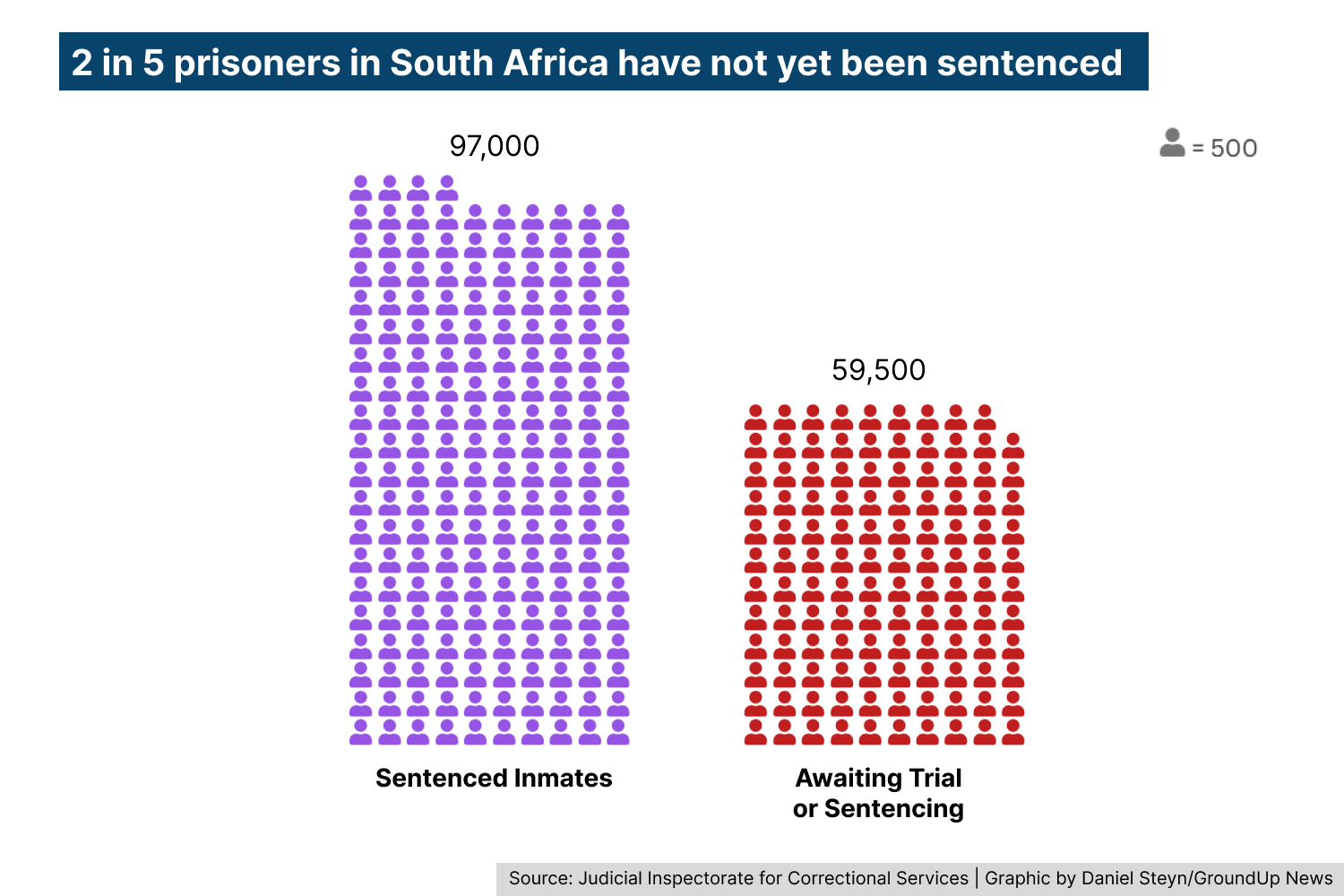

59,500 people in prisons have not been proven guilty or are still to be sentenced. Overcrowding is particularly bad in remand detention facilities. Graphic: Daniel Steyn.

Muntingh agrees with the Department of Correctional Services that there are urgent steps that must be taken to reduce the remand detainee population. The JICS has also proposed solutions to this problem.

Thousands of people are in detention because they have been granted bail but can’t afford it. This includes about 2,500 people who were granted bail for less than R1,000, says JICS in its most recent annual report.

The Department of Correctional Services and JICS both say that a major driver behind the growing remand detainee population is delays in the courts: bail hearings, criminal trials and sentencing proceedings simply take too long. People are often arrested while investigations are under way and if they are denied bail they can spend years in prison before facing trial.

Among the measures proposed by the judicial inspectorate to reduce the remand detainee population are speeding up court processes and stopping lengthy trial delays, establishing a bail fund for those who cannot afford bail, and reviewing bail processes and conditions.

GroundUp asked both the Office of the Chief Justice (OCJ) and the Department of Justice what is being done to eliminate court delays. OCJ spokesperson Lindokuhle Nkomondo said that the Chief Justice chairs a National Efficiency Enhancement Committee, which was established 12 years ago.

He also said that as part of a rationalisation process, the appointment of more permanent judges has been recommended.

But the Department of Justice said that it has not yet received the recommendations of the rationalisation panel.

Justice Minister spokesperson Tsekiso Machike said that the department’s Law Reform Commission is exploring policy and legislation changes to deal with overcrowding. This includes alternatives to remand detention for first court appearances, such as summons to appear in court, and potential changes to bail processes.

There are also plans to roll out new case management systems for criminal trials in the High Court, Machike said.

Another concern for JICS is the effect that mandatory minimum sentencing has on the prison population, especially those serving life sentences. In 1996, the country had 518 inmates serving life sentences. As of 30 March, the number was 18,795.

This is largely due to minimum sentencing laws for certain crimes. In 1998, minimum sentencing was first introduced as a temporary measure in response to a rise in violent crime, but the legislation was made permanent in 2008.

Among other consequences of the law is that those sentenced to life after 1 October 2004, for crimes committed after that date, have to serve at least 25 years in prison before they become eligible for parole.

JICS has called on minimum sentencing laws to be abolished and alternative sentences that do not involve prison time to be considered for some crimes.

Muntingh says that minimum sentences have not proven to be a deterrent to crime. Violent crime is rising despite the minimum sentencing laws. The best deterrent is for criminals to be caught. But the dysfunction in the police force means this rarely happens.

Even when people do become eligible for parole, they have to deal with dysfunctional, under resourced parole boards and backlogs. The Minister of Correctional Services needs to personally consider every single parole application. Until June this year the ministry was combined with that of Justice and Constitutional Development, a large portfolio, and parole applications were piling up on the minister’s desk.

But, according to new Minister of Correctional Services Pieter Groenewald, the parole backlog has now been cleared. Groenewald told Parliament that since taking office, he has considered 599 parole applications. 570 of those were rejected and referred back for further profiling; 28 people were released on parole; and one was released on day parole.

Another measure promoted by Inspecting Judge of Correctional Services Edwin Cameron is for sex work and some drug crimes to be decriminalised. These crimes are a key driver of the remand detainee population.

Minister of Justice spokesperson Tsekiso Machike said that “decriminalisation of certain offenses are being considered”. This includes sex work. He said that a review of minimum sentences “will receive our attention in due course”.

According to World Prison Brief, 258 in every 100,000 people in South Africa are incarcerated. The world average is 177 per 100,000 people. South Africa has the 49th-highest incarceration rate in the world and the seventh highest in Africa.

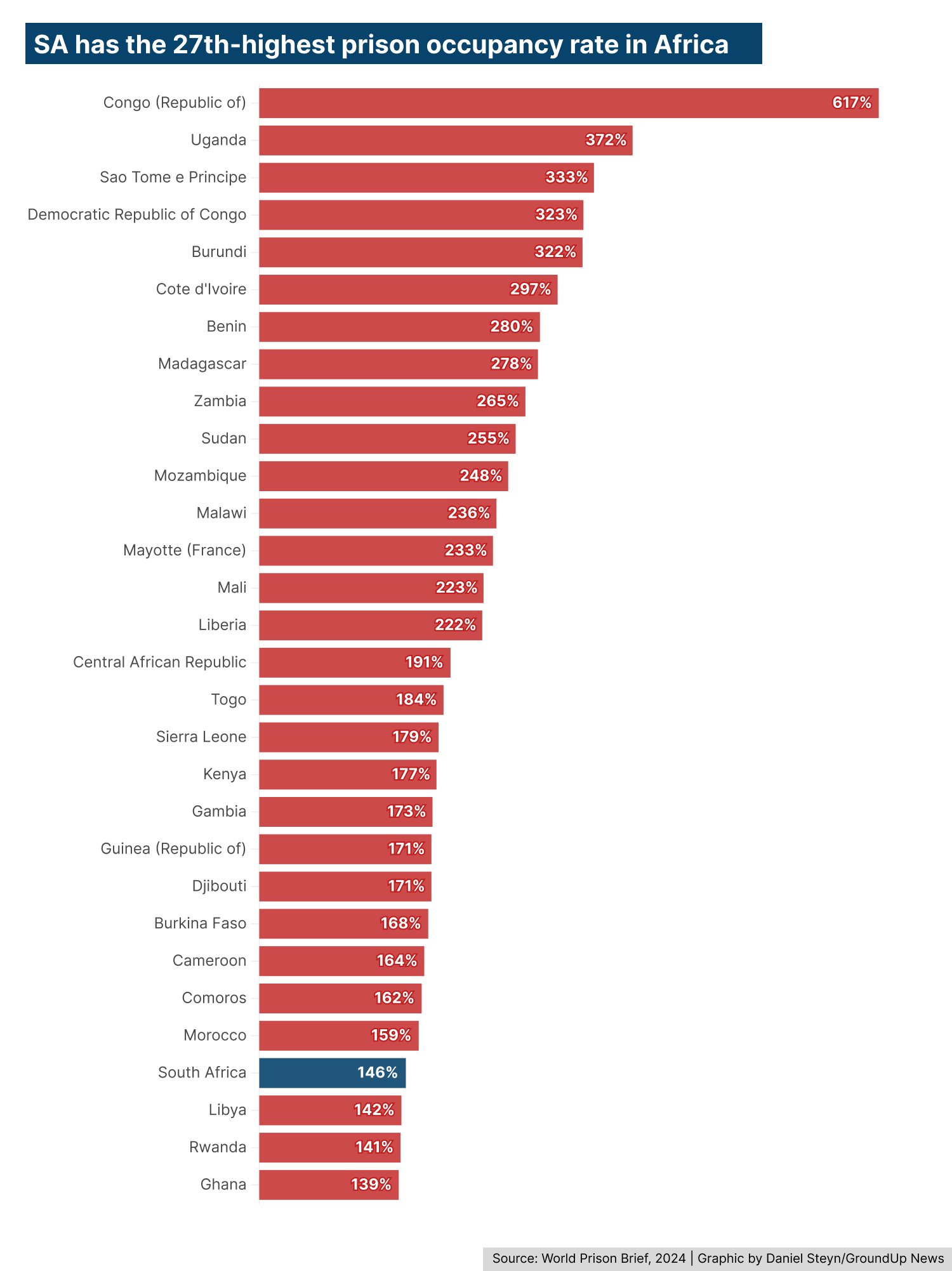

The average global occupancy rate of prisons is 130%. More than half of the countries in the world have overcrowded prisons. In Africa, overcrowding is particularly bad. South Africa’s occupancy rate of 146% ranks 27th among African countries, according to World Prison Brief.

Muntingh says that overcrowding has become a scapegoat for the Department of Correctional Services and is often used by the department to excuse inhumane conditions.

Muntingh says overcrowding “is not the start of the problem: overcrowding doesn’t cause you to torture people, it doesn’t cause corruption”.

There is much that can be done to alleviate the impact of overcrowding, says Muntingh, such as giving inmates more out-of-cell time, improving ventilation, and making sure ablution facilities are clean and functioning.

“It doesn’t matter how many people there are, the department has a duty to keep people in humane conditions.”

Prison overcrowding is a world-wide problem, especially in Africa. Graphic of top 30 countries in Africa with overcrowded prisons: Daniel Steyn.