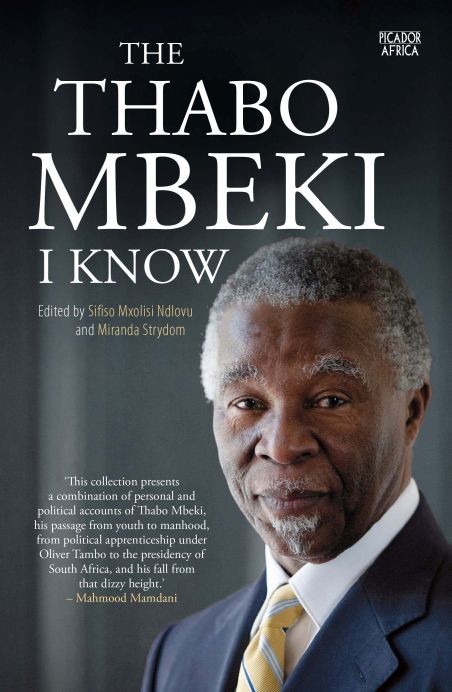

Front cover of new book on Thabo Mbeki.

2 August 2016

Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu and Miranda Strydom recently edited a massive collection of essays and comments in a book titled The Thabo Mbeki I Know. There is already an impressive library of books devoted to the second president of the democratic Republic of South Africa. Hence the question: why the need for a further volume about a man about whom much has already been written and who is still alive?

A read of the foreword to this collection by Barney Afafko provides the answer: “Few can argue with Patricia McFadden that Mbeki is a gift to the continent.” Apart from a few exceptions, the most important of which was penned by retired Constitutional Court Judge Albie Sachs, this book is determined to prove what a gift Mbeki was both to the continent and to South Africa. It is in short a sustained hagiography of more than 500 pages.

Take the foreword written by Mahmood Mamdani. In full disclosure I need to state that I have taught much of Mamdani’s work over many years and regard his contribution to Africa in general and South Africa in particular as important to the political debate; hence my surprise at the foreword that he has written.

Professor Mamdani’s central claim is, that “Zimbabwe was arguably one of Thabo Mbeki’s great successes; the other in spite of the furore and the controversy it generated, in hindsight, … was the HIV/Aids campaign.“

Mamdani argues that Mbeki’s policy with regard to Zimbabwe was “a great Yes, yes to reform as the alternative punishment, yes to regionalism as a way to stem the tide of growing external interference”. In his view, Mbeki responded to the demands of regime change by seeking to promote internal reform, particularly that of the electoral and government systems and to build a regional consensus behind it.

One needs to remind oneself that this foreword is written in the context of Zimbabwe in 2016. Only the myopic can fail to see that, tragically, Zimbabwe is a failed state in considerable chaos with a rapidly eroding democratic structure.

But leave aside the Zimbabwe of 2016. There is not a mention by Mamdani of critical elements of the earlier history. In particular, no word is expended on the manner in which Mbeki or his successor, President Zuma, suppressed the report written by Justices Sisi Khampepe and Dikgang Moseneke to the effect that the 2002 Zimbabwe election was rigged and could not be considered to be free or fair. By contrast, the South African government embraced this election, even though it possessed a report from two of our most distinguished jurists which came to an adamantly different conclusion.

Mamdani then moves onto the HIV/Aids debate. He embraces the view that the pharmaceutical industry was primarily concerned with the pursuit of commercial interest as opposed to addressing the health crisis that confronted the population of developing countries. He praises Mbeki for entering the debate and allowing a significant conversation to take place as to why the spread of Aids was so much faster in Africa than in Europe and the US. He contends that, until Mbeki’s intervention, the Aids lobby had succeeded in shaping the public narrative around the debate, and that to Mbeki’s great credit he brought a thoughtful and deliberative nuance to this vital conversation.

For Mamdani, Mbeki commendably commissioned an international presidential Aids panel which “presented the views of both sides of the debate and raised a lot of questions”. It was Mbeki’s triumph to show the power of the state in “mustering a counterforce capable of withstanding the greed and ambition of commercial interest”.

Reading these claims, one could be forgiven for believing that the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) was merely a lobby for pharmaceutical interests and that it was government which thoughtfully examined the complexity of the epidemic and arrived at a sensible response thereto. One might also be forgiven for forgetting that it was the TAC that was compelled to go all the legal way to the Constitutional Court as well as run a civil disobedience campaign to ensure that antiretroviral drugs were made available to those who required them in order to live. Or that it was Mbeki’s Minister of Health, Manto Tshabalala Msimang, who announced that, whatever the Constitutional Court might say, she would disregard its findings, before being slapped down commendably by the then Minister of Justice Penuel Maduna, after considerable protest from civil society and the judiciary.

Furthermore, there is no engagement with the damning findings to the contrary: in particular, two research articles, one by Pride Chigwedere and the other by Nicoli Nattrass, calculated that over 330,000 people died prematurely because of the South African government’s inept and confused policies under President Mbeki. The least one could have expected from a series of engagements with the legacy of Mbeki is a debate about these disturbing claims. Instead, we are told that any suggestion Mbeki could be responsible for the kind of crime he was charged with by Aids activists must be rejected with contempt.

It is not only Mamdani who defends the seemingly indefensible. In another piece in the collection penned by Aubrey Mbewu, we read of the ‘unfortunate demise’ of Virodene, the toxic industrial solvent that was heralded by Olga Visser and her husband Zigi as the solution to the epidemic. One recalls that before these two were exposed for their lack of science, they were invited to address the cabinet in 1997 and produced two patients who spoke of their remarkable recovery as a result of Virodene. We know that the cabinet then burst into “spontaneous applause” thereafter. There were significant claims that the government had sponsored this ill-considered programme. There is no mention of this in Mbewu’s remarkable defence of Virodene nor any attempt to engage with the fact that the TAC had demanded a judicial investigation into the entire Virodene saga.

To publish these uncritical, indeed hagiographic, statements in the context of what occurred in South Africa prior to the present government reversing policy (to its great credit) is nothing short of disgraceful. At the very least, for those passionate defenders of the Mbeki legacy, one would have expected a serious engagement with these arguments rather than an elision over each and every one of them.

To his credit Judge Sachs, in his brief contribution, calls Mbeki out in this regard by referring to his brother Dr Johnny Sachs who had written a passionate letter to Thabo Mbeki at the time of the HIV/Aids crisis about the pain that he felt that the ANC, which he had supported his entire life, was behaving in this irresponsible manner.

In typical style, Mbeki fobbed off Johnny Sachs. That Mangosuthu Buthelezi and Mavuso Msimang joined Judge Sachs in their disagreement with Mbeki about the HIV/Aids crisis does not appear to worry Mamdami or Mbewu in their claim that Mbeki was the hero of this entire episode.

That the question of HIV/Aids within Africa in general and South Africa in particular needs to be located within terms of poverty, inequality and the dire circumstances in which the vast majority of the South African population continue to live should not be, and, in my view, has never been, denied by those who fought the Mbeki regime on its policy. To the contrary, it is astounding that the book presents the idea that it was the government that caused the reduction of the price of drugs in its “heroic” fight against the pharmaceutical companies, forgetting that it was the TAC that litigated through the Competition Act and used political means to bring down drug prices radically; ligation, I might add, which garnered little support from the government at the time.

To be fair there are a number of chapters dealing with Mbeki’s economic policy which reflect a more serious consideration of the role of South Africa within the global economy and the constraints imposed on it, factors which, alas, are not given the same weight today.

There is much about Mbeki’s skilful role in negotiating the passage from apartheid to democracy. These are achievements and they receive a justifiable examination in this book.

However, in seeking to turn Mbeki’s two disastrous policy errors into his most extraordinary achievements, this book can surely not be taken seriously by anyone who wishes to understand a legacy of a president that has proved to be so controversial. It would have been interesting to read a chapter dealing with the question of whether the Mbeki regime gave rise to many of the difficulties with which the country is confronted at present and in particular whether the economic policy chosen at the time of a commodity boom was truly directed to economic transformation. But that was hardly the aim of these praise-singers!

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.