1 December 2023

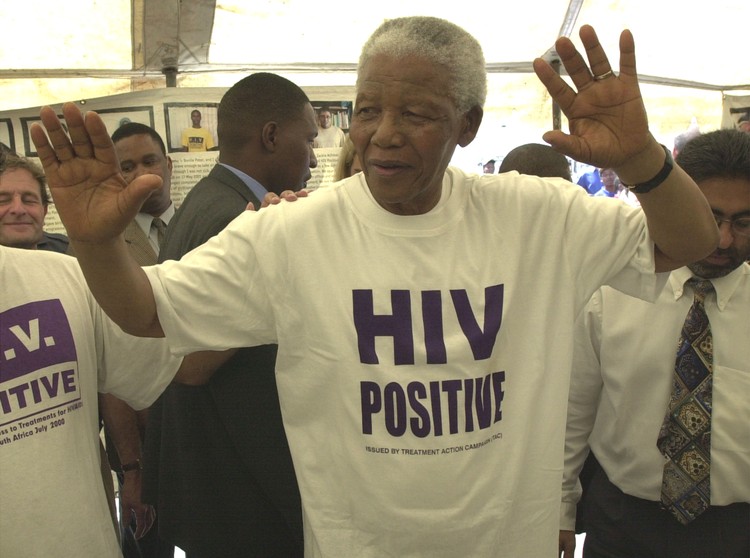

President Nelson Mandela in 2002 wore the Treatment Action Campaign’s iconic HIV-positive T-shirt to try to convince President Thabo Mbeki’s administration to provide antiretroviral treatment in the public sector. Photo: Brenton Geach (copyright reserved)

South Africa has some state-run systems that are working well. One of these is the HIV treatment programme. We quite possibly have the largest public sector chronic medicine programme for a single disease anywhere in the world.

Of the 7.8-million HIV-positive people in South Africa, about 5.8-million are on antiretroviral treatment, according to the Thembisa HIV model. About 5.5-million people get their medicines from the public health system.

This is an astonishing achievement. Every day millions of people take pills provided by the government that keeps them alive. It is a programme that has reaped huge public health benefits.

Most of the numbers in this article should be treated as approximate. Numerous data sources of varying quality are used to estimate life expectancy, infant and child mortality, number of people on treatment, HIV incidence etc. The Thembisa model developed by researchers at the University of Cape Town, in our view, does the best job of integrating the data coherently.

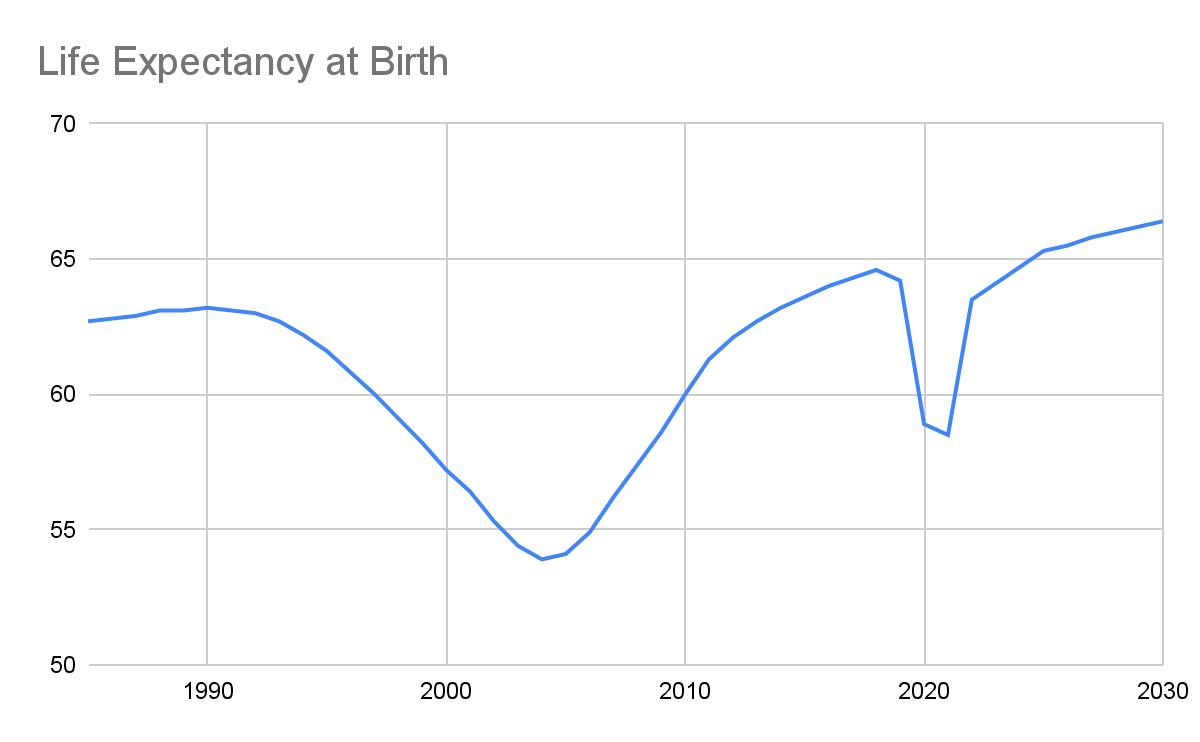

In 1990 life expectancy at birth in South Africa was just over 63 years. HIV caused life expectancy to plummet to under 54 in 2004. This was exacerbated by President Thabo Mbeki’s several-year delay in the rollout of antiretroviral medicines because he disputed the science of HIV.

Following pressure from activists, doctors and patients, Mbeki relented. The government announced an HIV treatment plan on 19 November 2003 and slowly began rolling out antiretrovirals in 2004. Gradually the decline in life expectancy reversed. Today life expectancy is 64. (There was a sharp drop during Covid but we have recovered.)

The y-axis is age in years. The x-axis is year. Data for this graph is from the Thembisa model.

Also contributing to this improvement in life expectancy is “better prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and the introduction of new vaccines, such as the pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, for children,” explains the Treasury in a review of provincial health expenditure.

The same Treasury document states that the infant mortality rate decreased from 39 per 1,000 live births in 2009 to 25 per 1,000 in 2018. Mortality in children under 5 years decreased from 56 to 34 per 1,000 live births over the same period.

The government spends in the region of R20-billion a year on antiretrovirals, which is not even 10% of state health expenditure. This has been a very effective use of public money. Besides the lives saved, Economist Impact estimates that every $1 spent on the HIV response yields a $7 return on investment.

Antiretroviral treatment is available in most of the country’s public sector clinics. In many areas, a pick-up point service allows patients to receive treatment closer to home. This is particularly valuable for those who live far from clinics and cannot afford transport.

The number of AIDS deaths peaked in 2005 at about 265,000. As antiretroviral treatment was rolled out, AIDS deaths started to drop. In 2022, fewer than 50,000 people were estimated to have died of AIDS and AIDS deaths are expected to drop to about 40,000 a year by 2030.

The left y-axis is number of deaths. The right y-axis is ART coverage. Data for this graph is from the Thembisa model.

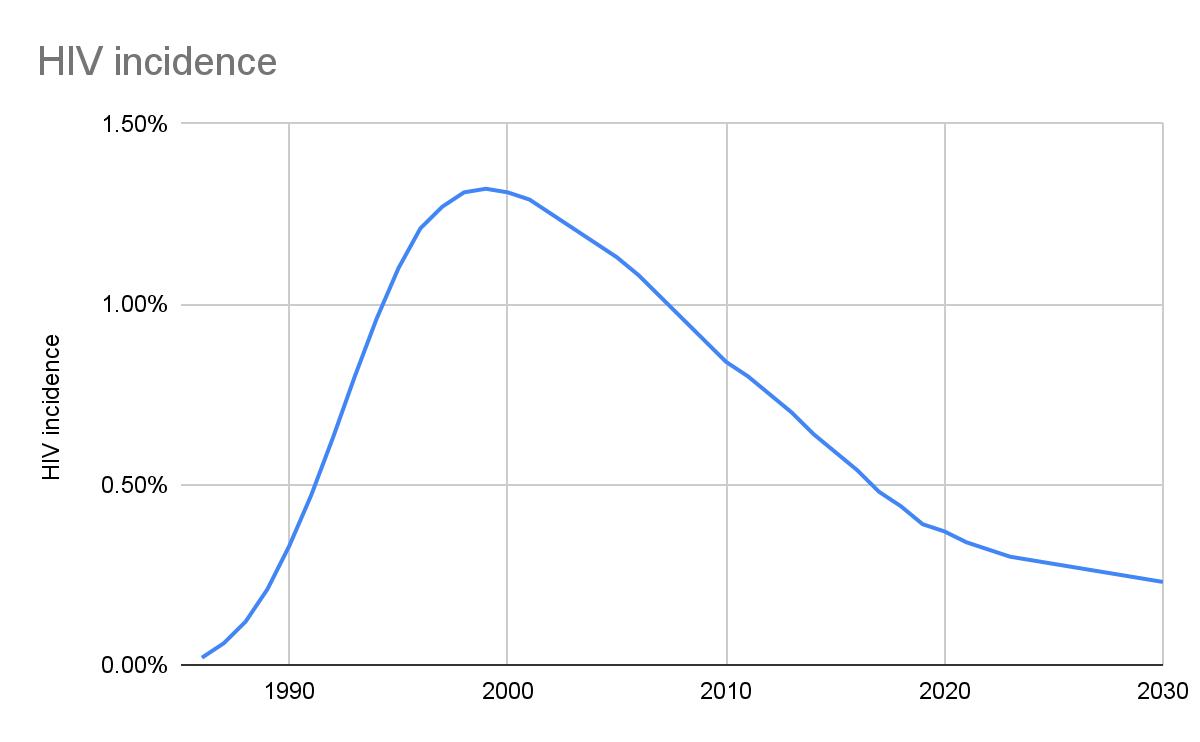

Estimating the number of new HIV infections annually is especially difficult and the numbers here should be treated with caution. Again, Thembisa is the source we use.

But there is no reasonable doubt that new HIV infections have steadily declined. This, from a high of nearly 540,000 in 1999 to about 175,000 in 2021.

Because population size changes, HIV incidence is perhaps a more useful measure though. HIV incidence is the number of new HIV cases a year divided by the number of people at risk of getting the disease (i.e. the uninfected population). It peaked at 1.32% in 1999. It was down to 0.32% in 2022 and is expected to fall to 0.23% by 2030.

Data from this graph is from the Thembisa model.

HIV can be transmitted from mother-to-child during pregnancy, during labour, or after birth through breastfeeding. These forms of transmission dropped sharply after the implementation of the mother-to-child transmission prevention programme in the 2000s. In 2004, there were 76,000 new cases of mother-to-child transmission. By 2022, there were 7,200.

The x-axis is number of people. Data is from the Thembisa model.

The United Nations has set a 95/95/95 target to end HIV as an epidemic: 95% of people with HIV to be diagnosed, 95% of those diagnosed to be on treatment, and 95% of those on treatment to be virally suppressed.

According to the Thembisa model, South Africa reached the first of these targets in 2023, with an estimated 95% of people with HIV being diagnosed.

But work still needs to be done to reach the other two of these targets. 80% of people diagnosed with HIV are on antiretrovirals - and according to the Thembisa model projects this will rise only slightly by 2030.

The percentage of people on antiretrovirals who are virally suppressed — in other words, with fewer than 1,000 copies of HIV per millilitre of blood, is currently about 93% according to Thembisa.

Data is from the Thembisa model.

Leigh Johnson at the University of Cape Town leads the Thembisa AIDS model. He says that Thembisa’s data suggests that the biggest barriers to reaching the targets are high rates of treatment interruption and difficulty re-engaging people after they have stopped taking treatment.

“This is especially a challenge among men, adolescents and young adults. Making health facilities more accessible (longer opening hours, shorter queues) and making it easier for people to transfer between facilities should be prioritised, with minimal red tape for people who restart treatment after an interruption,” says Johnson.

As reported by Spotlight, a 2023 HIV Investment Case, prepared by HE2RO, an economics research unit at University of the Witwatersrand, emphasises that with careful planning and implementation, the 95/95/95 targets can be reached without putting further strain on an already strained fiscus.

Cost-effective interventions, according to HE2RO, include increasing condom provision, hiring more staff to link HIV-positive people to treatment, scaling up HIV testing, and prevention pills.