Photo by Masixole Feni.

5 August 2015

Little by little, the management of compensation for sick and injured workers is being shifted from the state to the private sector — and in view of the problems in the Workers’ Compensation Fund, this may not be a bad thing, writes Pete Lewis.

Since May, the administration of compensation claims for sick and injured workers in the iron and steel industry has been managed, not by the state, but by a private company owned by the mines.

This follows a regulation under the 1993 Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act (COIDA) gazetted by the Minister of Labour last year, handing over the administration of compensation claims for workers in the iron and steel industry to the Rand Mutual Assurance (RMA), whose key shareholders are large mining companies. The shift affects about 60,000 employers, and half a million employees, accounting for about 11% of total contributions to the Compensation Fund.

The Compensation Fund is financed by a national statutory wage levy on employers. But for the past decade or more, the Fund has been beset by problems, as the office of the Auditor General, and the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Labour have noted.

Injured and sick workers have to wait long periods, usually years, for their claims to be settled and payments to begin. Fraudulent claims by medical professionals, and internal fraud by employees, have affected the Fund, as has as the failure of employers to meet the statutory requirement to verify claims on behalf of their employees.

Some private hospitals are owed large sums of money for treatment of injured or sick workers, for which they have received no reimbursement from the Fund.

The Portfolio Committee has probed the extended and expensive use of external consultants by the Commissioner’s office.

Injured and sick workers have to wait long periods, usually years, for their claims to be settled and payments to begin.

Attempts to deal with the huge backlog of unsettled claims, estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands, have been a constant theme. This year, a task team within the Compensation Commissioner’s office has tried to tackle 93 issues raised by the Auditor General, ranging from weak internal controls and staff shortfalls in both core business and financial controls, to unresponsiveness to client inquiries and court orders, and an outdated and cumbersome contribution assessment structure which is open to abuse.

The failure of the Department of Labour to solve these problems is the main reason for the latest round of privatisation of the administration of the system.

The Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act gives the Director General (DG) of the Department of Labour wide powers and duties to run the system of compensation, including appointing advisors and medical assessors to assess claims. The Minister of Labour appoints a Compensation Commissioner to administer the Compensation Fund, and assist the DG. The Commissioner has a staff of public servants comprising one chief director, eight directors, and three deputy directors, as well as other administrative officers.

The Commissioner reports to a Compensation Board, which advises the Minister but does not have executive powers. The Board includes representatives of organised employers and workers (COSATU, NACTU and some non-affiliated unions), the Departments of Labour and Health, and mutual associations in the mining and construction industry, as well as medical experts. Executive management of the Fund is the responsibility of the Minister and Department of Labour under the DG.

This complex combination of civil service administration and Board oversight under executive political control has failed over a long period.

But this is not for want of trying. A proposal from the Compensation Board that it should be given executive powers was discussed but ultimately rejected by the Minister. From 2009, ten decentralised administrative centres for the provinces (two in Gauteng) were established to help collate documentation, in an effort to reduce the backlog of unsettled claims by employees. But by the year 2010-2011 - the latest year for which an annual report of the Compensation Commissioner has been published by the Department of Labour - more than 80% of claims were still registered and settled in Pretoria.

An attempt to employ a handful of medical officers to ceritfy claims failed because suitable candidates were not identified, or dropped out.

The Compensation fund had assets worth R28bn in 2010/11, but only paid out R800m.

The one thing everyone agrees on is that the Fund is very large, with total assets of R28bn in the year 2010/11, a year in which it paid out total benefits of only… R800m. The reserves of the Fund have been growing, unsurprisingly in view of the slowness of claim management, and under-reporting of accidents and diseases.

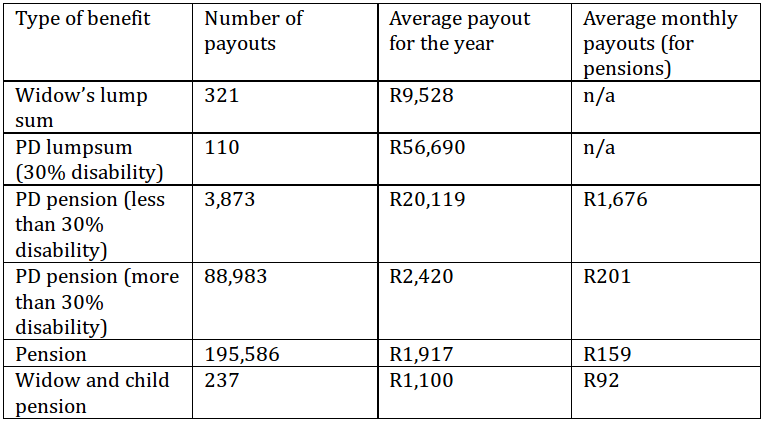

The table below shows the low level of benefits paid out.

Analysis of claims paid out by COIDA Compensation Fund for death, or permanent disability, for the year 2010/11. Source

Altogether 289,110 claims were settled for the year. With a total of 13.3 million employees counted in the Labour Force Survey for 2011, the vast majority of whom earned salaries low enough to bring them into the COIDA system, this means that only 2% of employees were covered for death or permanent disability through work in that year.

The 2010/11 report gives no details about the origin of the claims settled — which industries or sectors for example — and no breakdown of causes of accidents and illnesses. There is no discussion of the overall effectiveness of the scheme in addressing the actual burden of serious work-related injury and ill-health in the economy as a whole.

When the predecessor of COIDA, the Workmen’s Compensation Act, was promulgated in 1941, the RMA, wholly owned by the mining employers since 1894, was licensed by the Department of Labour to administer levies and claims regarding all deaths, injuries, and occupational diseases suffered by mine workers, other than TB and Silicosis, which were and still are the responsibility of the Department of Health, through the Medical Bureau of Occupational Diseases. This system for respiratory illness amongst mineworkers faces its own serious problems . In 1990, RMA formed a company to continue its function under licence from the Department of Labour.

The Federal Employers Mutual Association (FEMA), formed by the large construction companies in 1936, was likewise licensed in 1941 to manage workers’ compensation claims for injury and disease in the construction industry, and still does so. Both the RMA and FEMA maintain their own ring-fenced employer contributions to the scheme, as well as adjudication and appeals procedures for claims, in line with COIDA, in terms of their licences.

So the recent handing over of the iron and steel sector to the RMA is a continuation of the privatisation of administration of the system that began in 1941.

Puleng Mninele is the Health and Safety Officer of NUMSA, the largest trade union in the iron and steel sector. He has experience as a health and safety officer in the mining industry, and has been working for NUMSA since 2007.

“Our experience with the Compensation Commissioner has been bad,” he says. “I have files and files of claims from our members, and the time taken to settle them can be upwards of five years, even up to ten years. The same applies to both accidents and occupational disease claims.“

“The system is very paper-intensive.”

“There is also a major problem with non-reporting of cases to the Commissioner, where employers do not obey the law requiring them to report all work-related injuries and sickness. There are many cases where employers offer production bonuses to workers, who then cut corners dangerously to earn the bonuses, which causes accidents and exposures to dangerous chemicals. With under-reporting by employers, as well as the time each claim takes, there is no penalty on employers who turn a blind eye to dangerous work practices to get production up.”

“I have files and files of claims from our members, and the time taken to settle them can be upwards of five years, even up to ten years.“

Numsa supported handing over iron and steel to the RMA, says Mninele. “It has got to the stage when injured workers needing treatment for work accidents are turned away by doctors, because the doctors say they never get paid by the Compensation Commissioner when they submit their costs according to the COIDA. The same goes for workers who need prostheses after an accident — they cannot get them because the manufacturers don’t get paid for them by the Compensation Fund, as they should do. RMA came to the unions in the sector before the gazette appeared, and had discussions with us, asking for our support for them taking over the sector from the Compensation What really impressed us was that they were offering to settle all valid and verified claims within 30 days of lodging them. We are considering requesting representation on the Board of RMA as well, so that we can be involved in strategic discussions about how the system can benefit workers.”

Asked if he thought the shift to the RMA would address the problem of under-reporting of injuries and occupational disease, he acknowledged that RMA did not have an inspectorate to assess safety at work. “But we use our own shop stewards and health and safety reps to report incidents and unsafe conditions to the Department of Labour inspectors.”

Richard Spoor is an attorney who represents workers in claims and appeals arising from injuries and disease caused by work, and litigation. He believes the move of iron and steel employers to the RMA will bring benefits in terms of efficiency.

“The Compensation Commission is in a shambles, and the move to outsource a large chunk of its business was born out of necessity, whether or not there was some lobbying,” he says.

“There will be efficiency gains in the form of lower premiums for employers in the sector, and faster settlement of claims for workers. The RMA is far more open than the Commissioner’s office to reviewing decisions when appeals and complaints are lodged. The COIDA Commissioner’s office is defunct, and simply does not respond.”

“The Compensation Commission is in a shambles, and the move to outsource a large chunk of its business was born out of necessity”

But, Spoor says, there are still big problems with the whole system of compensation. “The first of these is that compensation is based on a calculation of impairment, not of disability, and this discriminates against manual workers. For example, permanent damage to a hip femur is rated under COIDA as 9% impairment, but someone with this type of disability will never work again in a manual occupation. Compensation under COIDA does not reflect this. It is an archaic calculation unrelated to the real lifetime loss sustained by the injured worker.”

“The second major problem is that the cost of COIDA insurance to the employer does not relate to the cost of prevention, so reckless employers regard their COIDA premiums as a tax on business. Reckless employers are subsidised by safer employers.”

One reason why health and safety is poor in South African workplaces, Spoor says, is that the compensation system “is not doing what it is supposed to do — penalising unsafe employers and forcing improvements to safety and health at work.”

He says the whole system needs reform, whether or not it is privatised.

“Administrative privatisation can help if the law requires all employers to join the scheme, sets a minimum contribution to the fund, and sets strict liability for employers for accidents and occupational diseases. Thereafter premiums can float on sound actuarial principles based on claims experience for individual employers. Trade unions should consider working on proposals for comprehensive and fundamental reform to COIDA along these lines,” says Spoor.