26 August 2021

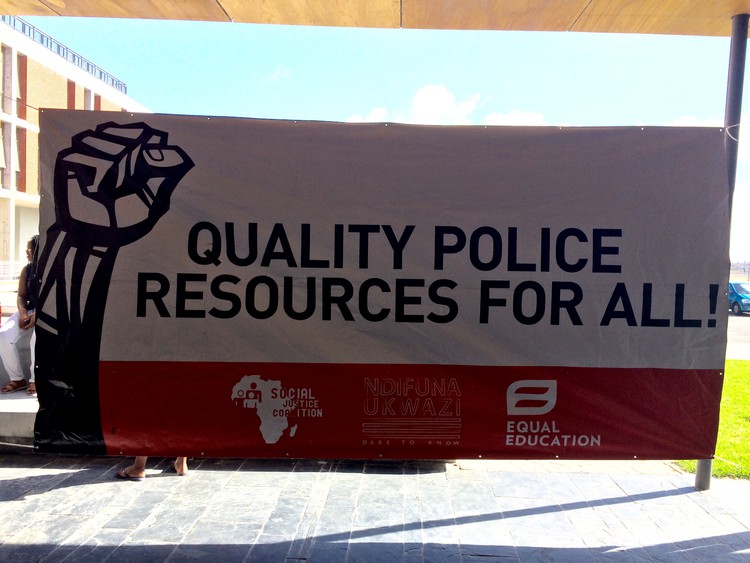

Dozens of residents spoke at a commemoration event with the Social Justice Coalition about how crime and policing has only gotten worse in the seven years since the Khayelitsha Commission of Inquiry ended. Archive photo: Natalie Pertsovsky

It has been seven years since the Khayelitsha Commission of Inquiry into policing and crime made its recommendations yet the situation in the township has only got worse, say residents.

On Wednesday, people living in formal and informal homes in Khayelitsha voiced their concerns during a virtual event hosted by the Social Justice Coalition (SJC).

Following a complaint by civil society organisations to the then Premier Helen Zille’s office in 2011, she announced the establishment of a Commission the following year.

The complaint alleged systemic failure by the South African Police Services (SAPS) in Khayelitsha to prevent, combat and investigate crime, take statements, open cases and apprehend criminals. This, they said, resulted in a breakdown in relations between the community and police.

Former Constitutional Court Judge Catherine O’Regan and former National Prosecuting Authority Head Advocate Vusi Pikoli were appointed as Commissioners.

On 25 August 2014, the Commission presented its findings and recommendations. It found that there were serious, overlapping policing inefficiencies. These included a lack of regular patrols, unanswered phones at police stations, poor detective work, widespread vigilante killings and policing based on “chance and luck” and not on “intelligence”. It also showed that there was a breakdown in relations between the police and the community.

We looked at the combined crime statistics from two precincts in Khayelitsha (Khayelitsha and Harare). Murder is the most reliably reported statistic. These have shown no sign of decline since 2014, rising from 310 in 2014 to 413 in 2020. This supports the claim by residents that crime has got worse since the commission (see the table below).

| Year | Total crimes reported |

Murders |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 10,167 | 266 |

| 2012 | 11,280 | 315 |

| 2013 | 12,193 | 300 |

| 2014 | 13,869 | 310 |

| 2015 | 15,032 | 287 |

| 2016 | 14,420 | 327 |

| 2017 | 15,131 | 353 |

| 2018 | 13,494 | 334 |

| 2019 | 12,679 | 387 |

| 2020 | 11,907 | 413 |

Ziyanda Stuurman is an author and policy manager at the Poverty Action Lab at the University of Cape Town. On Wednesday, she said the Commission was incredibly illuminating about the way police work in communities across the country.

“SAPS will tell us, until they are blue in the face, that they respect human rights and the communities that they serve.” She said the Commission showed this may be true on paper but not in practice in under-resourced communities.

She said even without time frames for the Commission’s recommendations, communities could mobilise and ask Police Minister Bheki Cele and other government departments to account for failures.

This was echoed by Nomzamo Zondo, director of litigation at the Socio-Economic Rights Institute, said the commissions into Khayelista and Marikana both illustrated how state resources are disproportionately geared to provide safety, security and comfort to part of the population while “millions of people living in informal settlements are sitting in neglect”.

BM Section informal settlement resident, Thobile Funani said, “When there is crime taking place, police blatantly tell you that they cannot come. But when it’s time for them to come to shebeens and raid alcohol, they will willingly come.”

Funani said women being killed by their partners was common in the area yet no arrests are being made. “There was an incident where I was arrested while trying to stop a fight between a husband and wife who were stabbing each other. The Commission doesn’t seem to have had any impact.”

Site B resident and SJC member, Ntuthuzelo Vika said the community’s distrust of the police led to vigilantism. “There is a lot of fear among people in informal settlements because they get robbed while going to a police station to open a case. There are also many instances where police say they cannot enter an informal settlement because it’s dark and there are no roads.”

According to the SJC, “One of the most damning findings of the O’Regan-Pikoli Commission of Inquiry was that human resource allocations appeared to be systematically biased against poor black communities. The Commission concluded that “the survival of this system is evidence of a failure of governance and oversight in every sphere of government”.

On 31 March 2016, the SJC along with Equal Education and the Nyanga Community Police Forum asked the Equality Court to compel the Minister of Police, the National Police Commissioner and the Western Cape Commissioner to revise the police’s human resources allocation process. After numerous delays, the case was heard in November 2017 and again in February 2018.

Judge MJ Dolamo found, in December 2018, that the allocation of police resources in the Western Cape unfairly discriminated on the basis of race and poverty. But in January 2019, SAPS applied for leave to appeal the Equality Court’s ruling.

Updating GroundUp on Wednesday, Khensani Motileni of the SJC’s said that developing guidelines on visible policing in informal settlements was yet to be addressed in court. She said the SJC had filed papers in the Constitutional Court in April this year regarding these guidelines which Minister Cele opposed. She said they were waiting on directives from the ConCourt.