9 December 2024

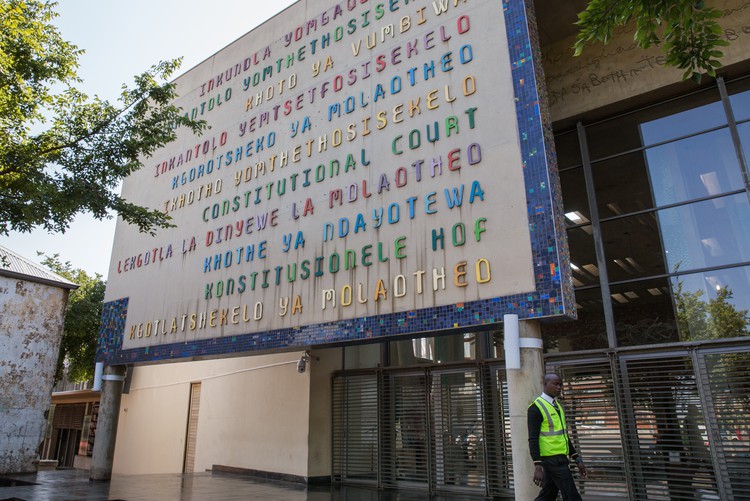

It is taking years to bring relatively simple matters to a close in our courts. The Constitutional Court is not setting a good example when it comes to delivering judgments on time. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

South Africa’s justice system is almost paralysed. It is taking years to bring even simple matters to a close. This is a crisis that undermines the rule of law.

Here are a few examples that GroundUp has reported:

We could list many more examples including ones that show the feeble pace of disciplinary processes at the Judicial Service Commission and Legal Practice Council.

If you get caught up in the justice system in South Africa expect to struggle for years and to spend a lot of money – with no guarantee of a satisfactory outcome.

What are the reasons for this sorry situation? And what can be done to fix it? I asked a few lawyers and judges.

There is an acute shortage of judges. According to the latest annual report of the judiciary for 2022/23, there are 248 judges. This is a mere 2% more than in 2011/12, despite the population having grown by nearly 20% since then. Judges in the Cape and Gauteng high courts, the busiest ones in the country, are especially overworked.

One sitting judge told me it’s hard to get simple things done. Judges are frustrated that they still do not have autonomy over their administration. Their admin staff are employed by the Department of Public Service and Administration instead of directly by the Judiciary itself. This may seem a bureaucratic nuance, but it is a fundamental problem because staff are not accountable to the judges but to the government. There is consequently not a harmonious work relationship, at least in some courts.

One lawyer I spoke to says poor investigations by SAPS result in criminal cases being delayed, especially in magistrates’ courts where most of these cases are heard. Poor coordination of witnesses, lawyers and court staff leads to matters being postponed when people are not available.

This is compounded by overworked and inexperienced prosecutors and magistrates. In a recent case in which GroundUp was the applicant, a magistrate could only deliver her order to us several days after she wrote it because the court’s email and printers were not working. Her order is a mess. Even though it seems to be in our favour, it’s poorly written and missing something crucial, so we have decided to appeal a case we won; it is Kafkaesque. This magistrate, working in a dysfunctional court, is insufficiently trained to do her job.

Then there is the legacy of Dali Mpofu. He has perfected the use of Stalingrad tactics to delay justice for his clients, like Jacob Zuma. He has sought postponements on spurious grounds, initiated unlikely-to-succeed trials within trials, filed unnecessarily voluminous papers and cross-examined witnesses for absurdly long times. Other dodgy lawyers with dodgy clients are emulating him.

This kind of behaviour can only be stopped if judges become harsher on time-wasting tactics, refuse frivolous postponement requests, and insist advocates who abuse the system be disciplined, even disbarred.

There are too many judges who take too long to deliver judgments, often because they are overworked.

Even the Constitutional Court has not set a good example: judges are supposed to hand down judgments within three months but 32 of the 39 judgments the Constitutional Court reserved and handed down in the 2022/23 reporting year took longer than that. At the time of writing the court has five judgments that have been reserved longer than six months.

Lawyers I spoke to gave various reasons for why this might be. One suggestion strikes me as compelling: the court should more frequently order punitive costs against frivolous applications, of which there are far too many.

The Office of the Chief Justice (OCJ) is supposed to report regularly on late judgments. But its last report was published in May and only goes to the end of 2023. If even the OCJ is late, and with a report on late judgments at that, what hope is there that the rest of the creaking justice system can be fixed?