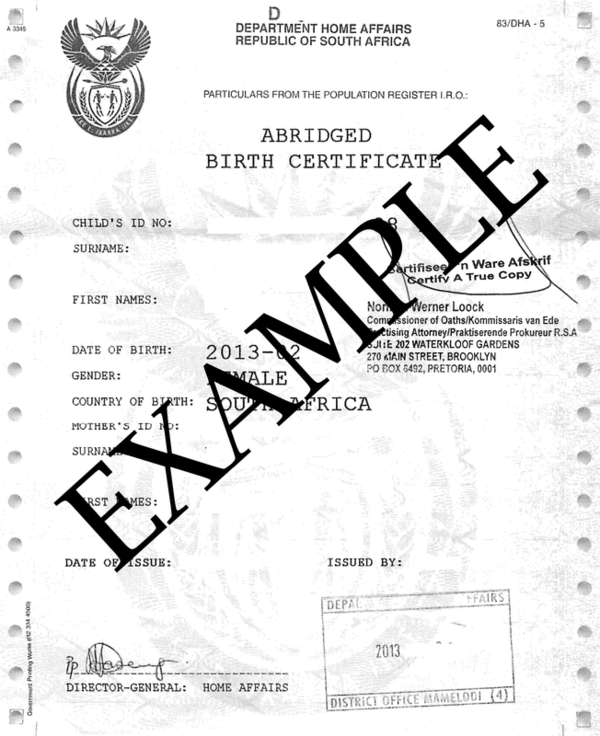

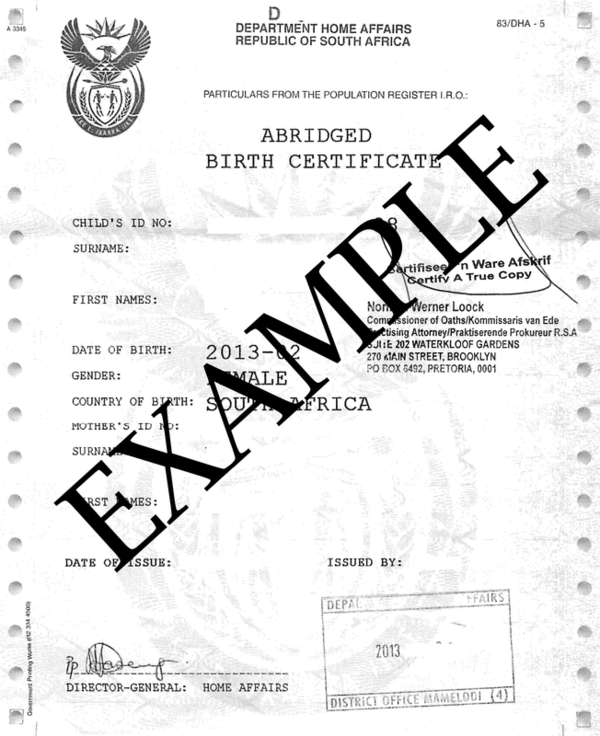

Picture courtesy of Africa Check (africacheck.org).

19 October 2015

When other kids their age are at school learning, Thandeka Plaatjies, aged 10, helps her mother with chores and plays with her siblings – Thandiswa, age nine, and Luthando, age seven – outside their home in Westlake township.

They live with their parents, Brenda Plaatjies and Thamsanqa Nziweni. They have never set foot in a classroom and can barely write.

Brenda Plaatjies came to Cape Town from Richmond when she was young to look for work. She has never had a birth certificate or an ID and she has never been to school. This has made it extremely difficult for her to apply for birth certificates for her own three children.

“I have never been to school. I lived with my father and I moved from relative to relative. I don’t know my mother. I don’t know when I was born,” said Plaatjies.

She met her partner, Thamsanqa Nziweni, in 2004 and she depends on his grant money for financial assistance.

Nziweni says he has spent a lot of money travelling between the Department of Home Affairs and the Department of Education and schools since his first child came of school age.

“I have been going up and down, asking anyone who is willing to listen to help us so my kids could get birth certificates … I have asked the department if I can’t register them myself because I have an ID. They are my children after all, but they refused.

“I work sometimes transporting kids to school while mine are at home. That doesn’t sit well with me.

“The oldest is growing up. She can’t even write her name,” says Nziweni.

In 2010, the couple were given forms by Home Affairs to take to Plaatjies’s father in Richmond to sign. When they returned, they were told that her mother also needed to sign the form and go with her to Home Affairs.

“I have never met my mother and her family. My father is very old. He tells me that my mother passed away and she had one sister, but he doesn’t know where she stays and if she is still alive.

“I have been searching for people who might know, but haven’t had any luck,” said Plaatjies.

Thabo Mokgola, Home Affairs media liaison officer, says every South African has a right to an identity. “It is her [Plaatjies] constitutional right. Further to that, it is equally required by law that Ms Brenda prove to the Department, beyond any reasonable doubt, that she is indeed a South African resident.

“In this instance, it is the mother who has to register her birth first through a late registration of birth process. To this end, a screening process will be undertaken, which involves interviews and verification of information.

“It is essential that the department satisfy itself that the mother is indeed a South African resident. The late registration of birth poses a serious security risk as it opens up possibilities for fraudulent entries into the National Population Register,’’ said Mokgola.

He said Nziweni can register the children. However, he too will need to prove beyond reasonable doubt that he is the biological father of the children.

“We just want our kids to go to school and get what we never had — an education. They have already lost too much time. Children their age are at school while they sit at home. We ask for help from anyone,” said Nziweni.

Western Cape Department of Education spokesperson Jessica Shelver says schools do require identification when a parent wants to enrol a child.

“However, in cases where the parent is unable to get an ID, and they are unable to get into a school for this reason, the parent must contact their relevant district office to ask for assistance.

“Schools may admit children who do not have birth certificates on condition that the parents provide the certificate within three months or evidence from Home Affairs that they have applied for the birth certificate,” said Shelver.

Since the GroundUp interview, Nziweni has been contacted by the Department of Education and was told to go to the nearest school, Westlake Primary School. He and was told by the principal that he would be contacted, but he hasn’t heard back at the time of publication. He says he is thinking of going back home to the Eastern Cape, hoping that the children will be able to go to school there.