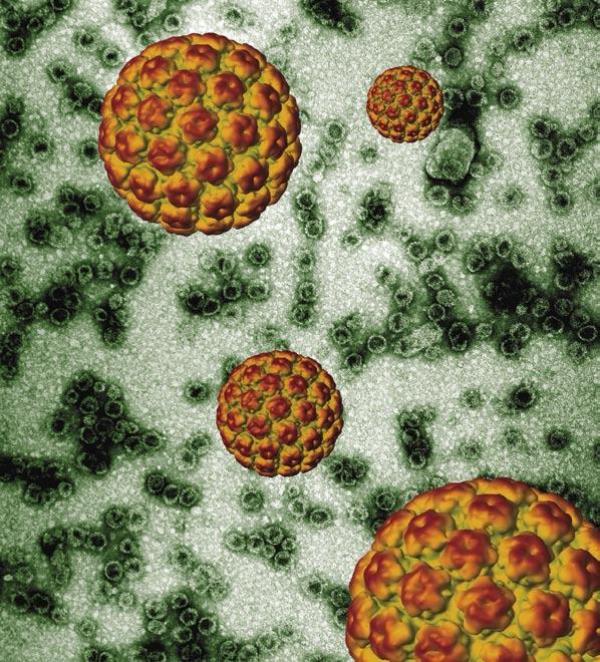

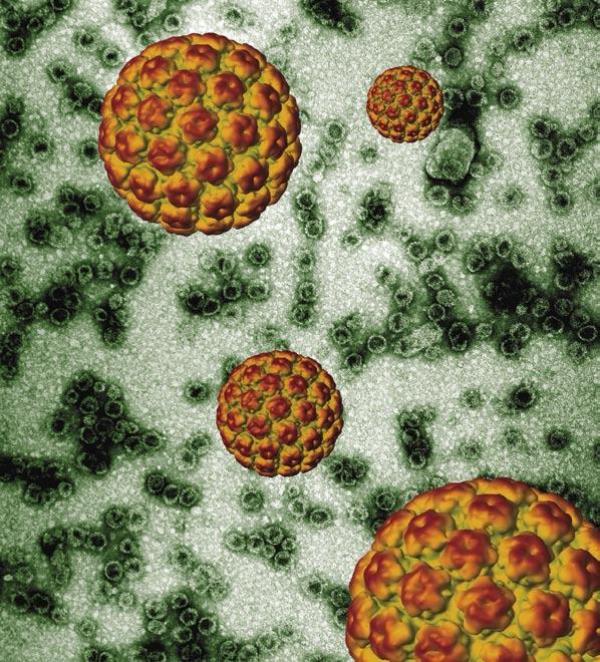

Image by Dr Arvind Varsani, Electron Microscope Unit, University of Cape Town. Released into the public domain by Equal Treatment magazine.

10 July 2013

It has been a little over a month since Health Minister, Aaron Motsoaledi, announced in his annual National Health budget and policy speech that the South African government will start administering free vaccinations against human papilloma virus (HPV) in schools beginning in February of 2014, but there is still much to discuss about the vaccination roll-out program.

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI), a fact which has led some to call it “the common cold of the sexually active world”. There are more than 100 strains or types of the virus. Anyone who has ever had sex can get HPV, and nearly all sexually-active men and women get it at some point in their lives. It is not simply spread through fluids of transmission, but also easily by skin-to-skin contact during sexual activity with another person. Such prevalence might lead some to think that HPV is a harmless infection, but this is a dangerous misconception. HPV, though most infected persons do not know they have it, can lead to serious health problems, including genital warts and certain cancers.

Indeed, the health consequence most discussed in relation to HPV is cervical cancer, the second most common cancer in women worldwide, and it usually presents no symptoms until it is dangerously advanced. 70% of all cervical cancer cases are linked to HPV. This distinct threat has led international health bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) to recommend that girls in the target age group of 9 to 13 years old receive vaccination against HPV. It is recommended that girls receive vaccination before engaging in sexual activity, so early vaccination is advised, although it is efficacious up to the age of 26 on average, after which it starts wearing off.

South Africa will follow in the footsteps of other countries taking official steps towards eradicating HPV in the national population. Australia was the first to launch a national program back in April of 2007. Three years later, researchers found a striking drop in both the genital warts cases in the country and the rate of high-grade cervical abnormalities in teenage girls. In October of 2011, Argentina introduced the HPV vaccine in their National Immunization Program. The vaccine has been given to all girls 11 years of age, and, in less than two years, the first dose has reached more than 80% of girls in the target age group, 60% have received the second dose, and 50% the third — results that demonstrate the impressive protective coverage that national campaigns provide.

While the United States does not have a national vaccination program, the vaccine is heavily advertised by physicians and media outlets alike, and, on 19 June, the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) released a study further demonstrating the positive effects of the vaccine in the country. The study compared HPV infection rates before and after the vaccine became available. In girls aged 14 to 19, infection with the targeted HPV strains fell by more than half. Among girls who had actually received the vaccine, the drop was even greater — nearly 90%.

Some African countries have also begun to provide the vaccine. Kenya and Rwanda are notable examples. However, South Africa will be the first African country to fund national vaccination with government money. In the cases of Kenya and Rwanda, the vaccine is funded by pharmaceutical sponsors or international aid organizations. South Africa, though, surpasses the economic limits set by such aid organizations and therefore has been refused funds for being “too rich” by organizations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Motsoaledi and other officials believe the threat is too high to abandon for lack of outside funds. Cervical cancer is the second most frequent cancer in South African women, according to the WHO, so the need is certainly evident. One in 26 South African women will develop cervical cancer and, of the approximately 6000 women who are diagnosed with cervical cancer in South Africa each year, many succumb to the disease. Launching this national vaccination roll-out is significant because it symbolizes an official commitment to meaningful engagement with women’s health issues.

There are currently two HPV vaccines available on the market, Gardasil and Cervarix. Both vaccines have been shown to prevent cervical precancers in women and are licensed and safe for use. Each vaccine, given as shots, requires three doses for full efficacy. Most importantly, the two vaccines are both effective against the diseases caused by HPV types 16 and 18, which are the two strains that cause most cervical cancers as well as the other HPV-associated cancers.

There are some key differences between the vaccines though. Gardasil, manufactured by Merck in the United States, is significantly more expensive than Cervarix, which is made by GlaxoSmithKline. Gardasil costs approximately R896.59 per shot, as compared to Cervarix which is more than R300 cheaper at R595.39 a shot. The difference in price can be explained through a difference in the non-cancer protections afforded by each vaccine. Gardasil protects against HPV types 6 and 11, while Cervarix does not. Types 6 and 11 are the two strains that cause nearly all cases of HPV-related genital warts.

While both vaccines are costly, South African finance and health officials are encouraged by international precedents that show lower prices may be negotiated. The Pan American Health Organization, for example, was able to significantly reduce vaccine prices for Latin American countries, offering a dose priced at approximately $13. Motsoaledi said in his speech that South Africa will enter negotiations to achieve similar ends.

Some experts are not so confident that this will be enough to significantly lower costs of the expensive vaccine. Professor Francois Venter, former President of the Southern African HIV Clinicians Society, lists this as one of his principal concerns with the vaccination plan. “I like vaccines, especially when they prevent people getting sick in a health system that battles to care for them.” But, says Venter, “I am not aware of a vaccine being rolled out successfully, en masse, that requires three shots like this, in older populations. As far as I can see, it will need to be done at schools which will be a huge operational issue. This is an expensive vaccine and will be an expensive programme.”

Representatives in the South African government have said that they hope to stem costs in ways that deal centrally with timing and school selection. The vaccination roll-out will only be given to girls in quintile one, two, three, and four schools. The assumption is those who attend quintile five schools can afford to individually purchase the vaccines. However, Motsoaledi’s office has said that significantly low income girls found to be attending quintile five will also be provided with the vaccine through special arrangements.

According to Dr. Jennifer Moodley, director of cancer research with the University of Cape Town’s Women’s Health Research Unit, the chosen age range and the decision to offer the vaccine in schools will require extra and meticulous planning if the program is to succeed. “Pre-adolescents are not the traditional age we target for vaccination programs – so careful planning will be critical to the success of the HPV vaccination program. We need to ensure that the school and health system are supported so that the vaccine can be delivered,” she said.

A further reduction in costs is sought through the delay of the third dose. While the first two doses of the vaccine will be given to 9 and 10 year old girls through the roll-out, the third will be offered after five years as a booster shot to grade nine girls. This decision may have its disadvantages. Firstly, the recommended schedule of the 3 HPV doses is only six months and the WHO states that the vaccine works best when it is administered over this timeframe.

Still Dr. Lynette Denny, a principal investigator and professor with the University of Cape Town’s Gynecology and Oncology Unit, stresses that “there is more and more evidence that two doses are as good as three doses.” While she knows of no clinical trials addressing booster shots of the HPV vaccine, giving the third shot as a booster could result in a “massive immune response” and offer positive long term protection.

Logistically, however, the department could lose track of some girls after five years. To put it simply, monitoring two age groups is certainly more complicated than monitoring one. Dr. Gerhard Lindeque, Professor of gynecology and obstetrics at the University of Pretoria, President of the Colleges of Medicine of South Africa (CMSA), and Chairperson of the South African HPV Advisory Board, believes that these are just some of the complications with the plan.

While he agrees with Denny that evidence increasingly demonstrates that two doses are just as good as three, he takes issue with the exclusion of some girls based on income and says that “this is not a good plan”. He is pleased that the national government has finally decided to address cervical cancer and HPV in the country, but believes the plan is somewhat “basic”. The South African HPV Advisory Board published a proposal several years ago making suggestions for the implementation of a national vaccination program, but “truncations [like attempts at cost reduction] added to the … proposal make it weaker”.

The South African health department has stated that the roll-out is a cancer prevention effort first and foremost. According to deputy director general in the health department, Yogan Pillay, this approach will be accepted more readily by parents who oppose anything of a sexual nature being introduced to their children, even a vaccination against a sexually transmitted virus. Such caution is realistic, despite countless research studies that demonstrate that there is no proof that vaccination will encourage earlier and riskier sex. An attempt to desexualize the vaccine will facilitate its adoption in primary school settings.

While the HPV vaccination roll-out is purposefully marketed as cancer rather than STI prevention,the vaccine inherently concerns the sexual health of South African women. Specifically, HPV is directly related to HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection in women. A 2009 study from the University of California, San Francisco found that HPV infection was associated with an increased risk of HIV acquisition in women. Eight similar studies reviewed during last year’s International AIDS Conference in Washington, D.C. found the increased risk of acquisition to be approximately two-fold.

Since 1993, cervical cancer has been classified as an AIDS-defining illness, meaning that diagnosis in an HIV-infected patient signals that their condition has progressed to AIDS and that antiretroviral treatment should be started. So the HPV vaccine can be seen as both engaging HPV and cervical cancer but also as a preventive measure for those who, later in life, develop HIV. There is even evidence that the HPV vaccine could benefit women who are already infected with HIV. A US study found that, even among women who tested positive for one type of HPV, the vaccine could effectively prevent infection with one of the strains that cause cancer.

This is significant especially considering South Africa’s unique relationship to HIV. Many of the women diagnosed with cervical cancer in South Africa are HIV positive. It could be that one of the ways of measuring the cost-effectiveness of the vaccine will directly engage the health of HIV-infected women in coming years. Denny recently conducted research among a pool of women aged 18 to 24 that demonstrated that the HPV vaccine is safe and can induce an immune response in HIV-positive women. This is only an indirect approach to addressing the needs of HIV-infected women however, according to Denny. “Is the HPV vaccine the best national program solution to addressing the HIV issue? On face value no – preventing HIV transmission, an HIV vaccine and treating HIV infected individuals is the best solution to HIV.”

However Venter is concerned. He says, “I haven’t seen enough data on the efficacy of the vaccine in HIV-positive people, and this would be a major group, especially if it is given to adolescent girls, where almost a third have HIV by the age of 21.”

There is one notable detail missing from the South African plans to launch the vaccination roll-out — boys. The vaccine will only be provided to girls in the target age range. This is not a reflection of lower risks for males. While the advancement of the disease is more rare in men, HPV can cause anal and oral cancers in infected men. Oral cancers present just as few warning signs as cervical cancer, though the prevalence of such cancers in South African men is comparatively low. However, similar rates have not stopped other countries. Australia recently became the first country, this past February, to offer the vaccine free to boys aged 12 to 13, and, beginning in 2014, boys aged 14 to 15 will also receive the vaccine as a kind of catch-up program.

The decision to not offer the vaccine to boys in South Africa is likely related to costs. The CDC recommends that both boys and girls be vaccinated for HPV because of the health risks that both groups face. While there are no widely recognized clinical trials that demonstrate the HPV vaccine’s protection against oral and anal cancers in men, there are numerous studies that show that the vaccine is safe in boys and prevents the development of genital lesions and similar diseases. Only Gardasil, the more expensive vaccine, is available for boys. The South African government is already struggling to federally fund the roll-out for girls. If quintile 5 female students are also refused the vaccine due to costs, it naturally follows that boys would not be offered the vaccine either. Still, if the vaccine can protect boys from genital warts and certain cancers as well, why shouldn’t they also receive the shots?

While she notes that there are “many advantages to vaccinating boys”, Denny sees the decision to exclude them from the national program as logical based on the differing nature of HPV in women as opposed to men and a dearth of funding: “The boys question is simply one of resources – in an ideal world all pre-exposed [to HPV] children should be offered the vaccine, but if you take a panoramic view, the greatest burden of disease associated with HPV is found in women, not men.”

Moodley agrees that excluding boys makes sense in the light of budget constraints. “Vaccinating boys has a number of benefits – however when costs and benefits are assessed – none of the research has shown that including boys is a cost-effective strategy. In developing public policy in limited resource settings such as [South Africa], one has to look at the greatest public benefit for the money spent.” For now, then, South Africa must focus on threats to women.

Lindeque agrees that “in a policy decision those who are at risk to get cervical cancer should be the first to be vaccinated”, and thus excluding boys from the national plan makes sense. He also says that the risks for boys might soon be inconsequential. “There is accumulating evidence that the high risk HPV types will also disappear in boys.”

Some of the hesitancy regarding the roll-out relates to the health care system as a whole. Some wonder whether the program will have great impact when the entire health care system itself needs improvement. However, many concede that this vaccination plan, at the very least, is a good first step to improve South African health as a whole. Moodley believes that ultimately addressing cervical cancer in the country must come from a “combined approach” of both primary and secondary prevention by way of vaccination and Pap test, respectively. It is important, she said, that overall “health systems are strengthened to deliver these strategies.”

Denny too views the HPV roll-out as one of a series of steps that ought to be taken towards achieving better health across the country and in particular women’s health. Vaccination efforts should not stop with HPV, said Denny. “I think vaccination should be linked to other important health interventions such as vitamin A supplementation, deworming, nutritional assessment and booster doses of diphtheria and tetanus.” Such a full process, she believes, is necessary if the vaccination plan is to succeed. “To implement HPV Vaccination we need a strong, robust and functional health system—and it does not all have to happen at once—it can be done incrementally.”