30 June 2022

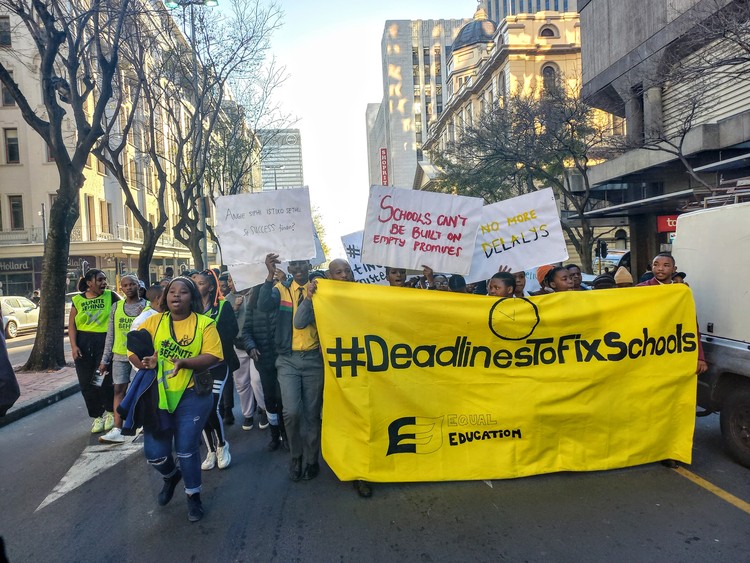

Learners and parents march to Parliament in Cape Town on Thursday against the draft amendments to the Norms and Standards for Public School Infrastructure. Photo: Marecia Damons

Learners marched to Parliament on Thursday to protest the draft amendments to the Norms and Standards for Public School Infrastructure.

The Department of Basic Education has proposed to remove the deadlines set in the regulations for when Government must eradicate pit latrines and provide basic services like water, electricity, and classrooms.

The public have until 10 July 2022 to comment on the draft amendments.

About 60 learners donned their school uniforms to march through Cape Town’s streets to Parliament on Thursday morning.

They are opposed to the proposed changes by the Department of Basic Education to its Norms and Standards for Public School Infrastructure regulations. These set a minimum school infrastructure standard that all schools have to meet.

Under the draft amendments, the deadlines for when the government must eradicate pit latrines and provide basic services like water, electricity, and classrooms have been removed.

The current regulations stipulate three, seven, and ten-year deadlines for when pit latrines and schools built from mud, asbestos, metal and wood must be eradicated. By these deadlines, schools also need to have access to water, electricity, fences and libraries.

On Thursday, marchers, organised by members of Equal Education (EE) and Equal Education Law Centre (EELC), demanded that existing deadlines in the current regulations remain. They are calling for the eradication of pit latrines at schools.

The activist groups want a meeting with the national and provincial education departments to discuss the progress in school infrastructure backlogs, and the reasons for MECs failing to meet previous deadlines.

Outside Parliament, learners and parents expressed their concerns over the department’s proposal to remove these deadlines.

“Why make promises to us and then at the end of the day not deliver?” asked Anathi Sikafu, a grade 12 learner at Cedar High School in Mitchells Plain. “We need answers from the minister on how she came about the need for this change,” she said.

Daphne Erosi, community liaison officer for EE parents, said schools will have to wait several years for infrastructure if the draft regulations are gazetted. “[Learners] are being taught under trees and have to use pit latrines. There’s no electricity, no water and the list goes on,” she said.

She said although they have not seen as much progress as they had hoped for, “at least there are deadlines”.

The legally-binding regulations, published in November 2013, state that every public school in South Africa must have access to water, electricity, ablution facilities, security, and internet. They also require schools to have libraries, science laboratories, and areas for physical education.

The department’s first deadline to ensure that schools had water, electricity, and sanitation was 29 November 2016. This deadline was missed by several provincial education departments.

The department was also meant to ensure that all schools had fences, telephones, and access to the internet by 29 November 2020, but this is not the case at many schools.

The department set a deadline for 31 December 2030 by when all norms and standards mentioned in the regulations are meant to be met. This deadline has also been removed in the draft amendments.

In a joint statement EE and EELC said the proposed changes to the school infrastructure law will see schools falling apart for “many more years”.

“Without deadlines that are written into law, learners and teachers could be waiting another ten or 20 years for their schools to be fixed. Without the legally binding deadlines, how can learners, teachers and parents hold the education departments accountable to fulfil their legal and moral duty?” the statement read.

“Without the urgency and accountability that is demanded by the deadlines in the school infrastructure law, poor and working-class communities will never know when their schools will be fixed,” the organisations said.

The organisations said Minister Angie Motshekga only adopted the school infrastructure law after years of “tireless campaigning led by EE members” and legal action.

According to the Department’s National Education Infrastructure Management System (NEIMS), in 2013, 45% (10,915) of South Africa’s then 23,909 public schools had pit latrines as toilets, 12% (2,925) had no electricity supply and 7% (1,772) had no water supply. Nearly a decade later, the number of schools with pit latrines reduced to 5,167, while 90 schools are still without electricity, it said.

EE and EELC have written to the department and asked it to extend the deadline for public comment to 30 July. The current closing date is 10 July 2022.

They are encouraging parents, teachers, learners and others to make submissions to the department.

The department did not respond to our questions about the draft amendments.