26 June 2025

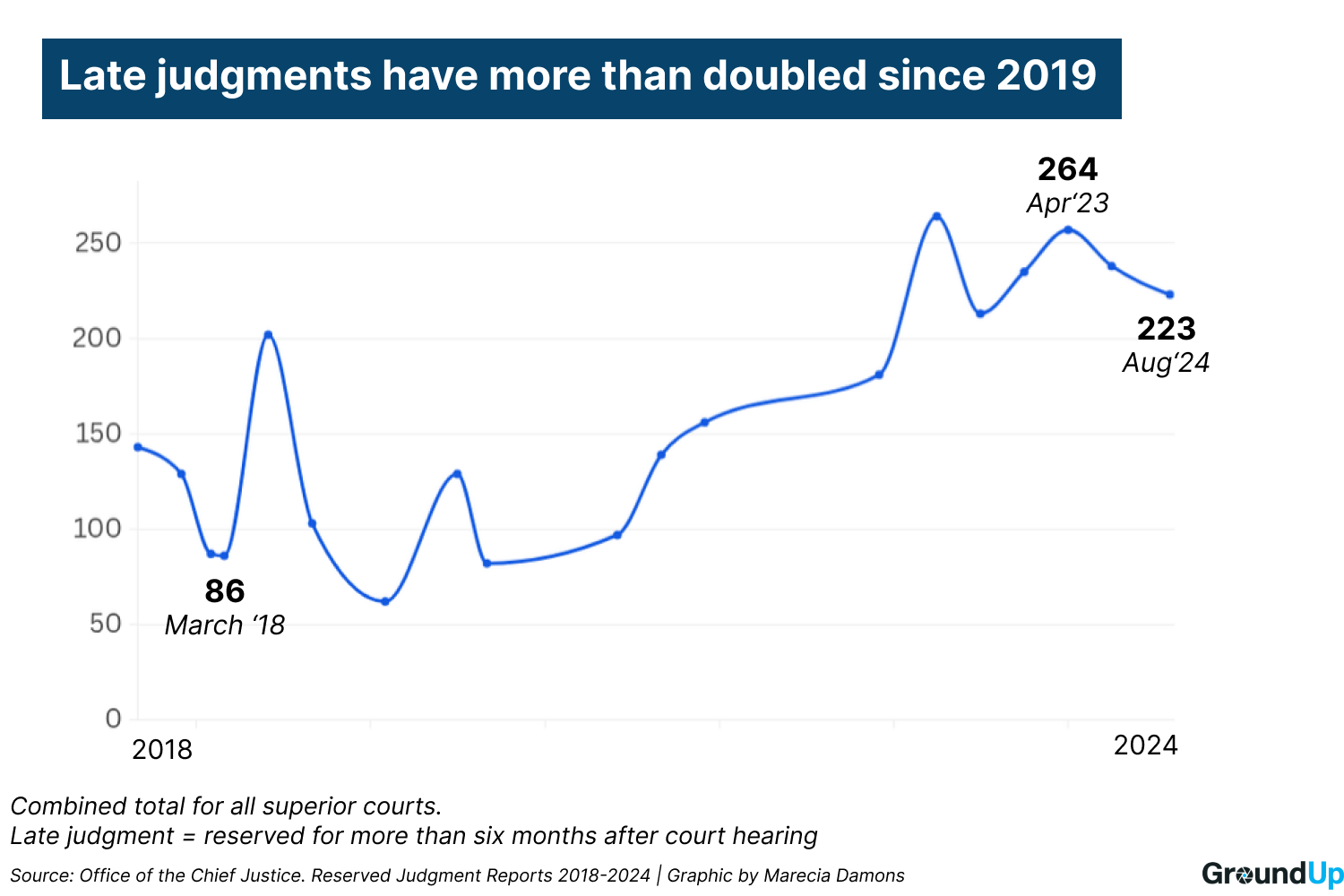

The number of late judgments (outstanding for more than six months) has more than doubled since 2019, when around 90 were recorded. Illustration: Lisa Nelson

In 2016, the landlord of farm worker Eric Lolo from Wellington issued eviction proceedings against him and his family in the Wellington Magistrates’ Court. Before the matter was finalised, it emerged that the Drakenstein Municipality could not provide emergency housing if the Lolo family were evicted. The case was paused while Lolo brought a separate application to the Western Cape High Court in 2017 to compel the municipality to meet its constitutional housing obligations.

The court reserved judgment in February 2021 and only ruled in Lolo’s favour in July 2022. The municipality appealed. The Supreme Court of Appeal heard the matter in November 2024 and reserved judgment. It still hasn’t been delivered.

Lolo’s case is not unique. Across South Africa, people are waiting months, sometimes years, for courts to rule on matters affecting their homes, livelihoods or access to services. Data from the Office of the Chief Justice (OCJ) shows the growing scale of late judgments.

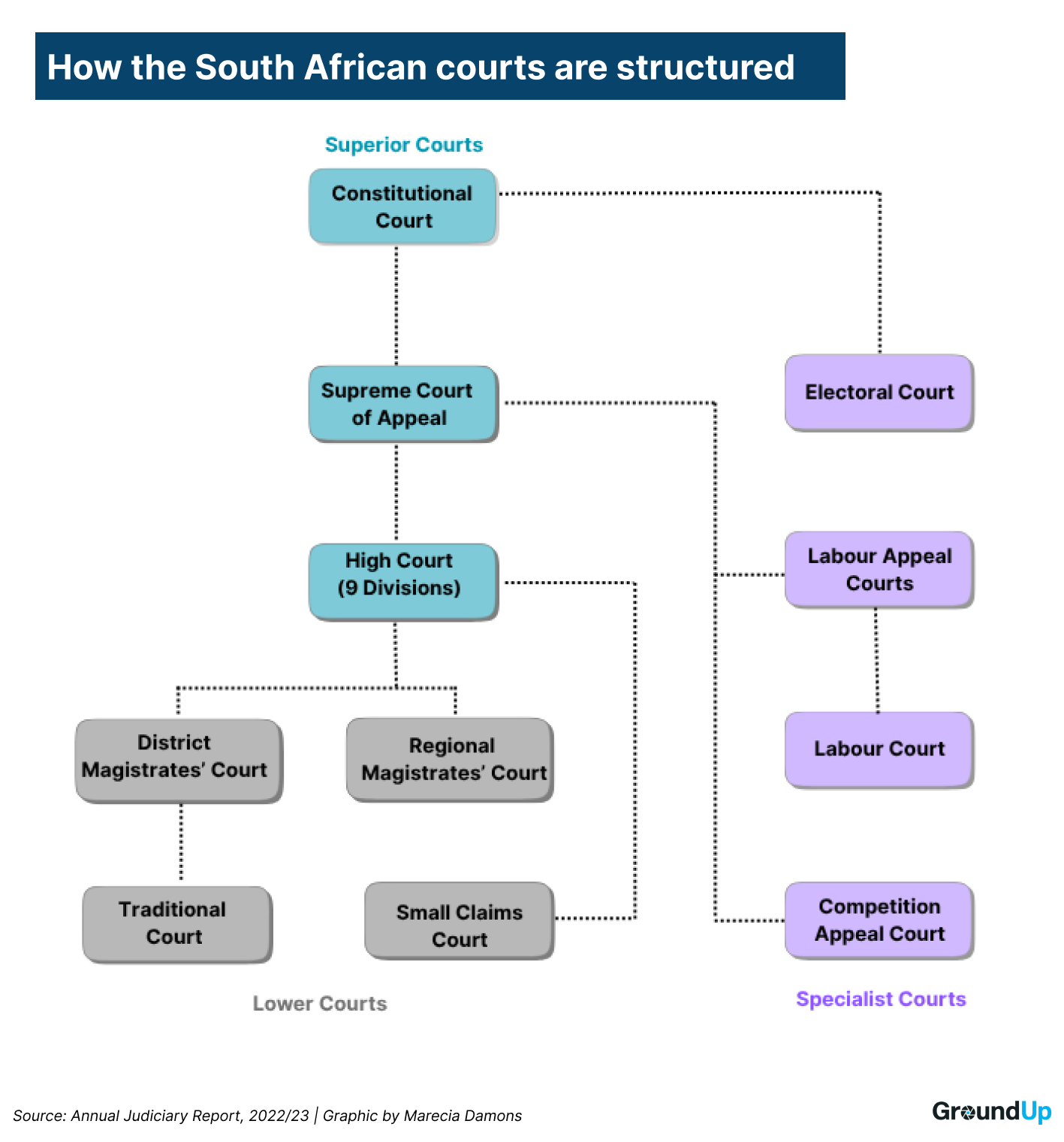

Instead of delivering judgment immediately or soon after a hearing or trial finishes, a court may decide to reserve judgment. The judicial norms and standards state that judgments should be handed down within three months of being reserved. But the OCJ now uses a six-month benchmark. Any reserved judgment still outstanding after that is considered late.

1,602 judgments were reserved between July and August 2024 across South Africa’s courts. Of these, 223 were late.

Previously, the OCJ published reserved judgment reports three or four times a year, typically after each court term. But in recent years, reports have come out irregularly. The latest list only reflects reserved judgments for the third term of 2024.

According to this list, 1,602 judgments were reserved between July and August 2024 across South Africa’s courts. Of these, 223 were late.

The number of late judgments has fluctuated since 2018, ranging from 129 to over 260. After dropping to 86 in March 2019, it spiked to over 200 by June. A temporary dip followed in 2020, but the figures rose again: 97 in June 2021, 156 in December, and 181 by the end of 2022. By April 2023, the number peaked at 264. The backlog persisted into 2024: 257 in January, 238 in April, and 223 in August.

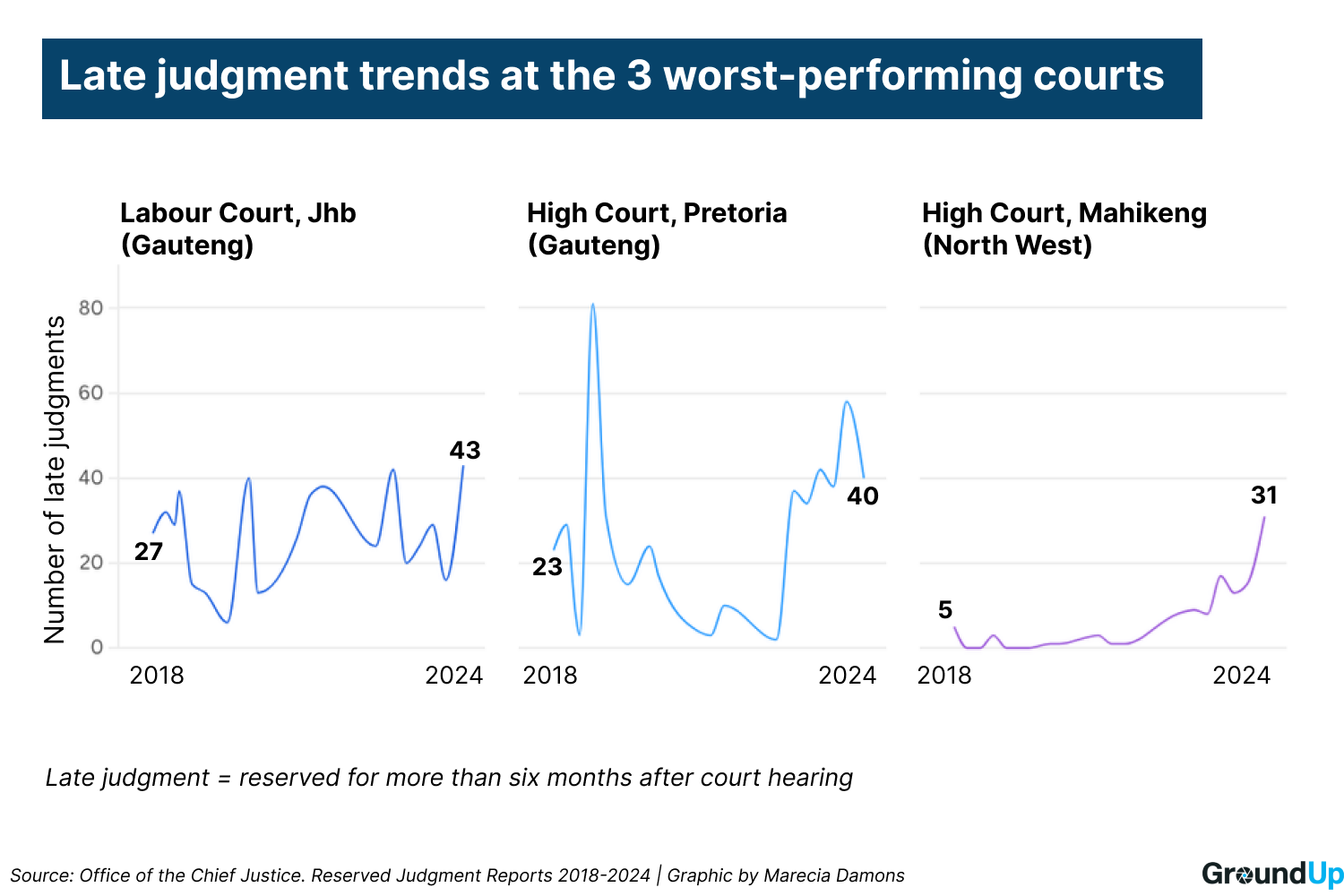

Three courts had the highest number of late judgments in August 2024: the Johannesburg Labour Court (43), the Pretoria High Court (40), and the Mahikeng High Court (31).

The Labour Court in Johannesburg has had many late judgments for years. Although numbers dropped in 2020, they rose again, peaking at 43 late judgments in August 2024. The Pretoria High Court had only three late judgments in March 2019, but this jumped to 81 by June that year. After a dip, the figure rose again to 58 in April 2024. The Mahikeng High Court had no late judgments for several years, but from 2022, numbers climbed, peaking at 31 by August 2024.

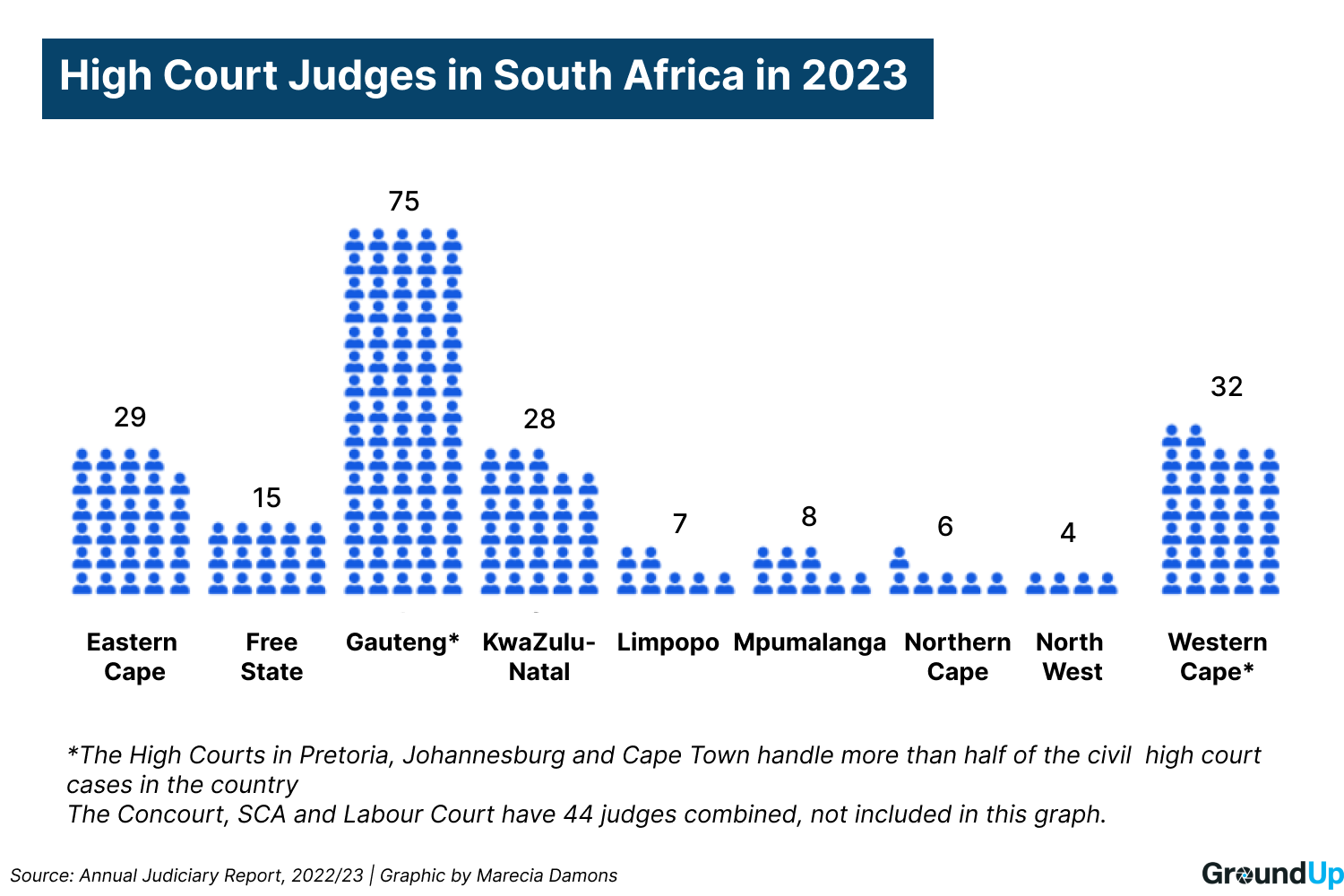

South Africa has about 250 judges, which has remained largely unchanged for years. Judges Matter researcher Mbekezeli Benjamin wrote that failing to increase judicial posts has put enormous pressure on the courts.

This strain shows. For example, the Gauteng High Court is setting trial dates as far out as 2031. Specialist courts are also under pressure. The Labour Court only has 13 judges to serve the entire country. During the 2024 elections, the Electoral Court had just two of its five permanent members, Benjamin wrote.

According to the last published judicial annual report, over 110,000 civil matters were heard in 2022/23. “Annually, 93% of cases at Superior Courts are civil cases,” the OCJ said. Only 3% are criminal matters, and 4% are mental health applications. Civil cases mostly involved the Road Accident Fund, health MECs and the police minister, while the most common criminal charges were murder, aggravated robbery and rape, the OCJ said.

“The Pretoria, Johannesburg and Cape Town High Courts together handle more than half of all civil superior court cases. The Johannesburg Labour Court deals with over half of all Labour Court matters, while Cape Town High Court handles 59% of mental health applications,” the OCJ said.

Courts in South Africa have too few judges, contributing to the hundreds of late judgments.

A 2022 report by Judges Matter covering South Africa, Namibia and Malawi found that rising workloads have not been matched by better support, more appointments, or filling judicial vacancies quickly. Judges reported inadequate support staff and heavy caseloads. Some said they were expected to find “innovative ways” to manage their workloads.

Durban High Court Judge Jacqueline Henriques, for example, delivered a ruling nearly three years after reserving judgment. She attributed the delay to the case’s complexity and a lack of support staff.

The Department of Justice’s 2024 report on High Court rationalisation described further pressures. Judges attending circuit courts reduce capacity at the main courts, forcing others to juggle multiple responsibilities.

“Judges are allocated more than one matter per day and sometimes three different matters per week,” the report said. This leaves “very little time for preparation”. As a result, “they have to write their judgments in the evenings and over weekends,” the report said.

Asked what support is provided to improve case management, the OCJ said judges are trained through the SA Judicial Education Institute, which offers courses on judgment writing, case management and constitutional rights. A stress and conflict management programme was also recently introduced to support judges under pressure, the OCJ said.

The OCJ said it had already amended court rules in 2019 to “alleviate congested trial rolls”. But “the courts are [still] congested and a shortage of judges has been identified as a major factor contributing to backlogs”.

“Whilst the shortage of judges and the review of the establishment is under consideration, the Minister [of Justice and Constitutional Development] is requested from time to time to consider the appointment of additional acting judges with a view to arresting the backlog escalation,” the OCJ said.

To help reduce delays, the Gauteng High Court has introduced mandatory mediation in civil cases. A March 2025 case audit found that only two of 59 Johannesburg cases and 11 of 339 Pretoria cases required a judge.

While Gauteng’s mediation directive applies only in that division, the OCJ said other divisions can adopt similar measures.

On the shortage of judges, the OCJ said retired Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke is currently leading a process to review judicial establishments and court jurisdictions.

The OCJ is also focusing on digitisation to prevent future backlogs and ensure timely judgments. “The Court Online system has been introduced in the Superior Courts to ensure electronic filing to enhance access to the people of South Africa, whilst increasing efficiency and reducing paperwork,” it said.

It said the civil online system functions in more than half of the High Courts, with full rollout expected by the end of 2025/26. Meanwhile, a system for managing criminal cases is also being developed and will be introduced over the next two financial years, the OCJ said.