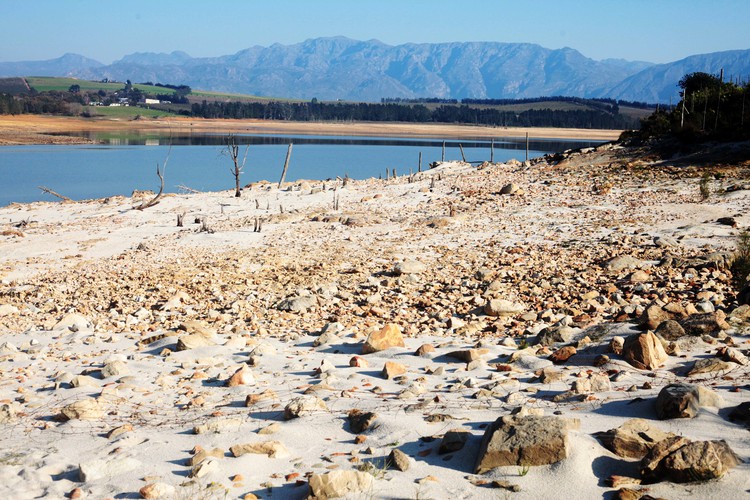

Water levels in Theewaterskloof Dam were already as low as 29% in June last year. Scientists have warned that forecasts of winter rainfall are unreliable. Photo: Masixole Feni

3 April 2017

Taps may run dry in the drought-stricken city of Cape Town and the south-western Cape as dam levels drop and rainfall forecasts for the region over the next few months are no better than chance, said local scientist Nicky Allsopp.

There is enough water in Cape Town’s dams to last another 100 days.

Allsopp, a scientist at the SA Environmental Observation Network (SAEON), said after two years of below-average rainfall, the south-western Cape was battling to survive.

The ground was so dry that the little rain that had fallen since October had just wet the top layer of soil and had not fed the dams that supplied water to the city.

“For the coming period to June, weather projections presented by the SA Weather Service are uncertain since forecasts for the south-western Cape have a ‘no better than chance’ probability of occurring. If rains don’t return to normal levels in the next few months, the taps may indeed run dry,” Allsopp said.

The current dry period measured at the Dwarsberg rain gauge in Jonkershoek was the worst since records had begun in 1945.

“There has been a massive reduction in stream-flow, and the rain since October has not made any difference to dam levels. The water flowing into the streams now is coming from water stored in rocks,” Allsopp said.

All mountains had cracks and gullies into which rainfall seeped and could be stored for years, replenished by winter rains. It was this stored water that was now seeping out of cracks and feeding the dams that fed Cape Town.

Allsopp said the current low dam levels – 27.3% of storage capacity – would have been even lower had the government had not embarked on a programme 20 years ago to hack down alien vegetation in the catchment areas. Unlike indigenous fynbos, alien trees like pines, gums and wattles are water guzzlers.

The last 10% of a dam’s water is mostly unusable, so dam levels are effectively only 17.3%.

Cobus Olivier of the SA Weather Service said one of the problems with rain forecasts for the country’s winter rainfall area was the lack of certainty. Although the latest long-term forecasts for the south-western Cape published this week had shown that some coastal areas may get higher than average rainfall between now and June, this could not be relied on with any certainty. This is what Allsopp referred to when she said rainfall forecasts were “no better than chance”.

Olivier said the uncertainty did not apply to the summer rainfall region.

“The computer models are not very good at forecasting those systems that bring the winter rain. They are good for the systems which bring the summer rain,” Olivier said.

The above-normal rainfall forecasts for the Western Cape therefore had a “low probability”.

The City said this week Capetonians were still using 25 million litres a day more than the target of 700 million litres.

It said if there were not good rains this winter, water restrictions might be intensified.

Asked what this would mean for households, Councilor Xanthea Limberg, mayoral committee member for informal settlements, water, waste services and energy, said there was likely to be a stop to all watering of gardens, even with buckets, no more topping up of swimming pools, and a reassessment of the water restriction exemptions.

Households use 55% of the city’s water supply and industry only 3.9%.

Limberg said this was because there were far fewer industrial customers in Cape Town than residential, and not all these industries required large amounts of water. Some used treated effluent.

All golf courses in the city used recycled effluent.

According to Rand Water, a golf course uses between 1.2 million and 3 million litres of water a day.

Most of the few commercial farms in the city used borehole water, Limberg said.

However, there were farms outside Cape Town’s municipal area that shared water from the same dams as the city, which accounted for about 40% of the total water consumption from these dams during summer.

When South Africa’s water laws were rewritten in the mid-1990s when Kader Asmal was water minister, all surface water came under the ownership of the state.

Guy Preston, deputy director of environmental programmes at the Department of Environmental Affairs and a former advisor to Asmal, said the intention had been to include borehold water in the revised legislation. However, it had been left out because of technical difficulties in monitoring and measuring flow.