21 July 2025

New regulations for the Employment Equity Act introduce five-year targets for the employment of black people, women and people with disabilities in companies in different sectors of the economy. There is a fierce legal battle over the regulations.

We asked Just Share’s Kwanele Ngogela to explain why he supports the regulations, and the Democratic Alliance’s Michael Bagraim to explain why he opposes them.

In this article:

South Africa’s new employment equity targets have provoked resistance from those who benefit from preserving the status quo. But contrary to alarmist claims, these targets do not undermine merit-based employment: far from being a trade-off against excellence, diversity is a catalyst for it.

More than two decades after the 1998 Employment Equity Act, workplace inequality remains deeply entrenched, particularly in the private sector, where black people, women, and people with disabilities are still under-represented in management and leadership.

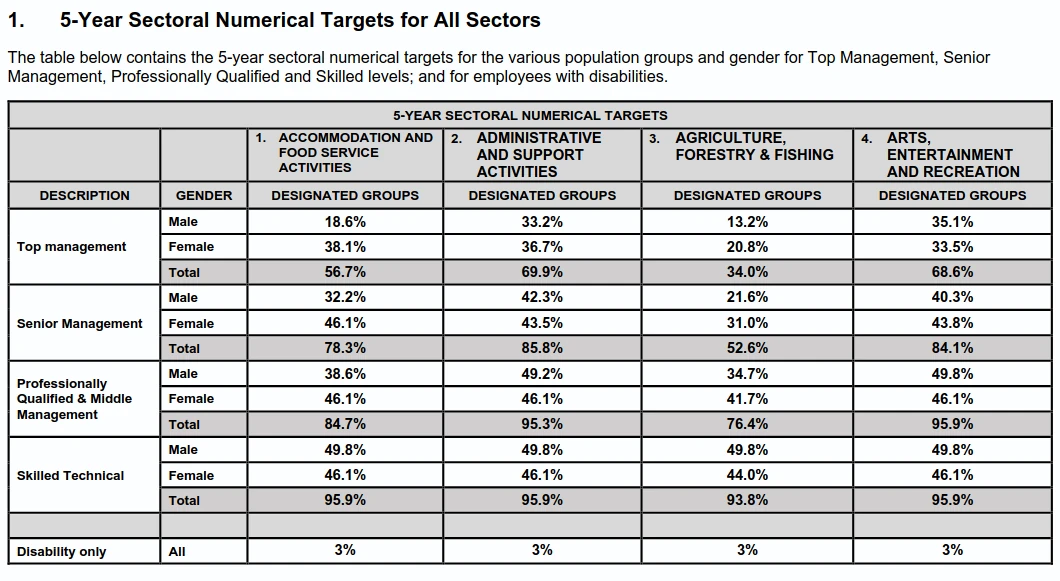

To address this, the newly gazetted Employment Equity Regulations introduce five-year, sector-specific targets for designated groups across 18 economic sectors. These targets operationalise the much-contested Section 15A of the Employment Equity Amendment Act, 2022, which empowers the Minister of Employment and Labour to identify national economic sectors and, following consultation, set targets to ensure equitable representation of suitably qualified people from designated groups at all occupational levels.

Much of the public backlash has been shaped by imported American rhetoric that pits “merit” against Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI), creating a false dichotomy. This ignores the true aim of employment equity: not to promote the unqualified, but to dismantle barriers which have long excluded qualified candidates from opportunity.

Data from the 24th Commission for Employment Equity Annual Report (2023/24) paints a stark picture. African, Coloured and Indian South Africans together comprise roughly 92% of the economically active population yet occupy less than a third of top management roles in the private sector. In contrast, white South Africans, who make up less than 8% of the economically active population, hold nearly two thirds of top management and more than half of senior management roles.

The gender gap is just as troubling: women make up 46% of the economically active population, yet hold only 27% of top management positions.

In government, white people occupy nearly 9% of top management and more than 10% of senior management posts.

These statistics expose the dominance of a demographic minority in leadership, particularly in the private sector. The real issue is not government over-reach, but years of government leniency. Businesses were given the space to determine their own transformation pathways and set their own targets. They failed to deliver.

Instead of seizing diversity as a strategic advantage, many companies reduced it to a tick-box exercise. They viewed transformation as a compliance requirement rather than an opportunity for innovation, improved performance and stronger human capital management. Yet, as the JSE Sustainability Disclosure Guidance (2022) suggests, “organisations with higher levels of diversity, particularly within executive teams, are generally better able to innovate, attract top talent, improve their customer orientation, enhance employee satisfaction, access more wide-ranging networks, and secure their licence to operate”. This underscores what many South African businesses have failed to grasp: that diversity is a catalyst for excellence.

Opponents often conflate targets with quotas, fuelling public anxiety and misinformation. Yet the law draws a clear distinction. The Employment Equity Act explicitly states in section 15(3) that affirmative action includes “preferential treatment and numerical goals” but excludes “quotas”. This couldn’t be more clear.

Section 15’s emphasis on “suitably qualified” individuals emphasises that merit must remain central to hiring and promotion decisions. Employment equity measures are not about displacing competence. They are about ensuring that qualified people from historically marginalised groups are given the opportunities they have long been denied.

Section 15(4) prohibits absolute barriers to employment for other people, and the regulations confirm that affirmative action cannot justify dismissals.

Claims that Section 15 violates constitutional rights by enforcing racial exclusion are not only legally unfounded: they are part of a pseudo anti-racist rhetoric which claims a concern for fairness but is really about preserving entrenched privilege.

The Employment Equity regulations provide that employers with justifiable grounds can qualify for exemptions from compliance with sectoral targets.

Those who argue that economic growth alone will solve racial disparities overlook the legacy of exclusion that shapes today’s economy. These critics frame DEI initiatives as a threat, caricature affirmative action as “reverse racism”, and strip the conversation of its historical and legal context.

Employment equity targets are not about retribution or exclusion. They are a measured, legal and necessary step to realise the vision of our Constitution: a more inclusive, fair and prosperous South Africa. If we are serious about shared growth, we must confront the inequalities that still define our workplaces, and commit to correcting them with urgency.

Ngogela is a Senior Inequality Analyst at Just Share and an MBA candidate at Wits Business School.

Extract from the Sector Target Regulations that are the subject of this debate. The table above lists four economic sectors. There are 18 in total.

There is a very emotional and super-charged discussion taking place across South Africa about employment equity.

The Constitution, which most of us see as the guiding document for the construction and well-being of our country, calls for redress of the wrongs of the past. But despite 31 years of democracy, and 27 years of employment equity legislation, the top tiers of the business community still reflect ageing pale males.

This is a difficult topic for people who did benefit from apartheid as many were both white and male.

But redress is an absolute, otherwise our society will never be healed. More than that, if redress doesn’t occur we will surely face upheaval and anarchy.

Our government has failed in its efforts to bring about equalisation.

The Employment Equity Amendment Act is not the solution.

The Democratic Alliance has chosen to institute court proceedings against the government over the Employment Equity Amendment Act and the regulations under the Act, on two grounds.

The first issue is technical. The matter should have been referred to the National Council of Provinces, as it affects the regions very heavily. There should be reference in the legislation to the various regions. The Western Cape has a different demographic to all the other provinces. The coloured population should be more representative in the workforce in these provinces. KwaZulu-Natal should have more Indian representatives.

The second issue is that the minister will be able to set quotas which are set in stone, regardless of factors influencing each employer, factors which are acknowledged in previous legislation.

We agree that something must be done to meet the objectives of the Constitution.

I have been a Member of Parliament for 11 years and have been practicing labour law, firstly as an advocate and thereafter as an attorney for over 40 years. When the Employment Equity Act was first enacted 27 years ago, we did not believe that that was the correct way to go. We still do not believe that it is the correct way to go. For 27 years our government has tried employment equity and social engineering. For those 27 years, we have had little to no redress. The top echelons of our business community are still pale male.

The majority in the government still believe that the Employment Equity Act is useful and they merely need to “tighten” up some nuts and bolts to enforce quotas and ensure redress.

These quotas are supposed to be met within a five year period and employers who haven’t reached the quotas will face massive fines.

Many of the businesses that I deal with on a daily basis, most of which are not owned by white people, have expressed their dismay and indeed their disgust. I can give hundreds of examples, but one that springs to mind immediately is a group of entrepreneurs who are part of the so called coloured community who started a business that today employs just over 200 people, mostly coloured. Their reaction to this legislation is that they will have to shrink to fewer than 50 people in order to be exempt from the new Employment Equity legislation. They would move the rest of their production to one of our neighbouring countries.

This story has been related to me literally dozens of times. Thousands of employers are not going to just throw up their hands and do nothing. I strongly believe that tightening the screws on useless legislation will cause havoc and create a lot more unemployment which is already standing at 43% in South Africa today.

The Democratic Alliance in the Western Cape has gone out of its way to cut red tape wherever possible. Despite negative employment equity legislation, unemployment in the province is now at 19%.

Employment equity cannot in any sense of the phrase be described as “fair discrimination”. For discrimination to be fair, it must be reflected in redress, which is not the case.

We need to urgently put in empowerment strategies enticing the business community to grow. We need to create new industries and lure foreign investors to our shores. Growth will ensure a more equitable reflection of the demographics of South Africa. Only growth and new opportunities will do what our Constitution requires of us.

Bagraim conflates numerical targets with quotas, a point clarified in the Employment Equity Act itself. Section 15(3) of the Act draws a clear distinction: employment equity includes “numerical goals” but explicitly excludes “quotas”. The regulations go further, allowing exemptions based on practical considerations like recruitment constraints, skill shortages, adverse economic conditions or operational restructuring. The portrayal of targets as quotas “set in stone” is inaccurate.

Bagraim suggests that even black-owned businesses will downsize or relocate to avoid compliance. But this claim rests on anecdote, not evidence. Regulation 16(5) of the Act outlines grounds for exemption, precisely to prevent such unintended consequences. Implying that the regulations will punish black-owned firms or force companies across borders is misleading.

Targets for “designated groups” include coloured South Africans. Bagraim is mistaken when he invokes coloured entrepreneurs as victims of the legislation. This misunderstands the law’s intent and application.

Bagraim’s claim that “only growth” can achieve equity is reductive. South Africa has had growth without transformation. Market forces alone have never been sufficient to undo the systemic exclusion rooted in apartheid-era privilege. That’s why the Constitution permits “legislative and other measures” to advance those disadvantaged by unfair discrimination. Employment equity is designed to confront and remedy exclusion where market forces have failed.

For 27 years, companies set their own targets. The result? Precisely what Bagraim admits: “The top echelons of our business community are still pale male.” That is not a failure of equity legislation; it is a failure of corporate will.

Bagraim cites the Western Cape’s lower unemployment rate as a success, while ignoring the racialised distribution of opportunity.

He offers no concrete alternative to sectoral targets, only a vague call to “entice” business and grow the economy.

Transformation is not incompatible with growth. But growth without transformation entrenches inequality. Sectoral targets, far from being rigid or punitive, are aligned with our Constitution’s vision of equality and shared prosperity.

The resistance to employment equity has definitely not come from those who have benefitted. All the research has shown that the selected few who benefitted from employment equity (some say it’s less than 200 people) have not said anything at all. Those who have resisted employment equity are those who are looking at the empirical evidence of a collapsing economy and the worst unemployment in the world. Furthermore, it must be stated categorically that a quota is set in stone and not subject to merit-based employment or other factors.

The only result we have seen from employment equity over two decades has been destruction. We all agree that there is workplace inequality and it is still deeply entrenched. The need for redress is now more urgent than ever. But redress does not come under the guise of social engineering. Redress will only be implemented with a growing economy and structural reforms such as education, transport, sustainable electrification and a functional business environment.

When the Minister of Employment and Labour was asked whether research had been done to explain why employment equity regulations had not worked in the past, she answered in the negative. In other words, we are now tightening the nuts and bolts on failed legislation even if we don’t know why it failed.

When we asked the minister who she actually engaged with in consultations to set these targets she merely referred to amorphous groupings. When we tried to engage the various sectors they all advised that no one had consulted with them at all. When we researched the number of cases referred to the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) for discriminatory labour practices based on race, the figures showed minimal referrals. In other words, people who have rights in terms of various pieces of legislation have not complained about discrimination on the basis of “race”.

To argue that the amendments are not referring to quotas is misleading. The real reason for the change is to set the quotas in stone. In essence, social engineering can never be justified as has been seen in history across the world.

This is the first debate in GroundUp’s new series. It is experimental and we will improve it over time. We choose a topic of interest and ask two experts with opposing views to explain their positions. The rules are as follows: