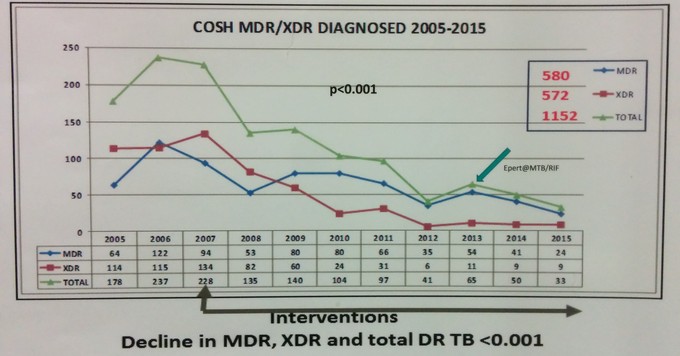

A graph displayed at the International AIDS Conference in Durban shows the decline in the number of drug-resistant TB cases in Tugela Ferry between 2005 and 2015. (Source: Friedland et al., AIDS2016)

16 July 2016

Tugela Ferry is a remote KZN district of 180,000 people that became infamous in 2006. Here it was discovered that 53 people had contracted a type of tuberculosis (TB) that was resistant to most anti-TB medicines. All but one of the patients died. All those tested for HIV were positive.

Further research showed that people were contracting this deadly germ in health facilities: the very places they visited in order to get better. And health workers themselves were getting sick and dying of drug-resistant TB.

Scientists and health activists were rightly alarmed. This extensively-drug resistant TB (or XDR TB as it is commonly called) signalled that an epidemic was emerging with deadly consequences. Until about 50 years ago, TB was pretty much untreatable. But then a spate of new medicines tested by the British Medical Research Council made TB curable with an effective cocktail of drugs that patients need to take for six months. The Tugela Ferry tragedy suggested we might be heading back to this pre-cure era. We still might be. But there’s hope.

Wonderful news was presented at the International AIDS Conference in Durban on Saturday. Professor Gerald Friedland showed how over the past decade, drug-resistant TB has been brought under control in Tugela Ferry. (Friedland has previously shown this in 2014, but he presented even more compelling data on Saturday.) There was no magic bullet. Rather, a combination of interventions implemented by motivated health workers and scientists appears to have done the trick.

Friedland explained what was done: infection control in the area’s health facilities was improved dramatically by, for example, keeping windows open, running fans and wearing masks. Patients who had coughs and were therefore potentially infectious, were separated from other patients by what Friedland half-jokingly described as a new kind of health worker: cough monitors. People who had been in contact with people with XDR TB were traced and tested.

The most accurate, albeit slow, type of TB testing (where the germ is grown in a culture over a period of weeks) was implemented. Resources were brought in to improve monitoring and surveillance. Instead of making hospitals the main place of TB treatment, people were increasingly treated in the communities where they lived.

Also, TB and HIV were managed together: all HIV-positive patients were tested for TB, and all those diagnosed with the disease were immediately put onto antiretroviral treatment.

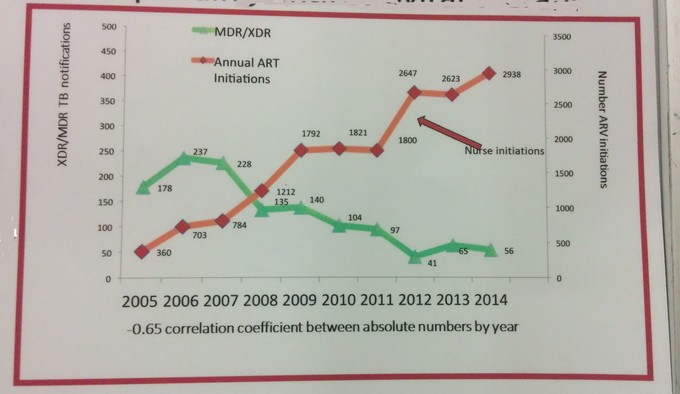

The following graph shows how as the number of people on antiretrovirals increased, the number of XDR TB cases dropped. This is not a coincidence: antiretrovirals have been shown to be very effective at reducing the risk of HIV-positive people contracting TB.

People with HIV without TB were also given a medicine called isoniazid to reduce their risk of contracting TB.

The good results were not immediately apparent. The death rate from XDR TB continued to be extremely high, dropping from over 98% at the start of the outbreak to the still extremely high rate of 82% by 2007. A total of 696 people were diagnosed with drug-resistant TB between 2005 and 2008, a large number for a small population. The worst year was 2006 when 237 people were diagnosed, but by 2009 it had only dropped to 140.

Yet as the graph above shows, there was steady progress, and in 2011 there were fewer than 100 drug-resistant TB cases diagnosed. In 2012, the number dropped to 41. The good results appear to be sustained since then. The rate of XDR TB cases dropped from 68 per 100,000 people in 2006 to 12 per 100,000 in 2015.

One concern that Friedland pointed out is that the number of people becoming ill with TB (including TB that can be treated – these are the vast majority of cases) continues to be high in Tugela Ferry, including among HIV-negative people.

This was a joint effort by scientists and health workers from the University of Kwazulu-Natal, American universities, a local NGO called Philanjalo, and the KZN government. A poster on display at the AIDS conference concludes that the drug-resistant TB epidemic in this rural area “has been stabilised and reversed.”

The question now is whether this happy outcome can be replicated across the country.

Some minor corrections were made to this article after publication.