20 November 2024

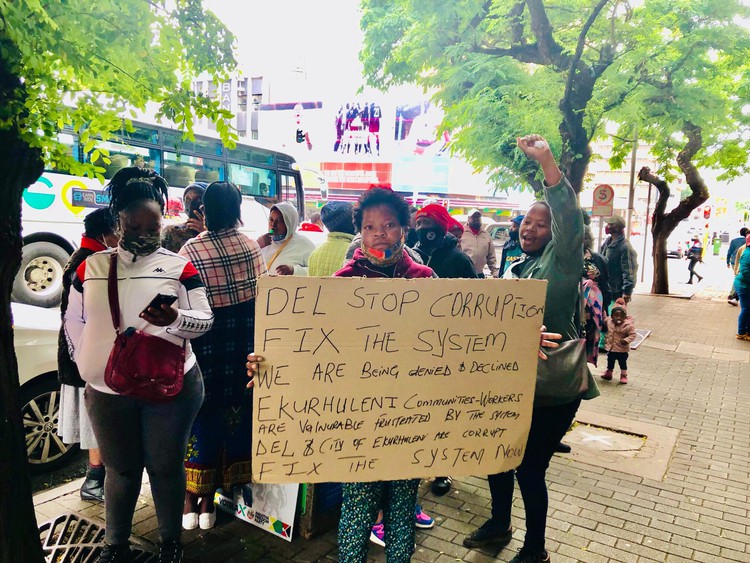

A protest organised by the Simunye Workers Forum in 2021. The Labour Appeal Court is to hear an appeal against a ruling that the forum be registered as a trade union. Archive photo: Kimberly Mutandiro

On Thursday, the Labour Appeal Court will hear a crucial hearing on the future of the Simunye Workers Forum (SWF) which represents more than 6,000 people working in the informal sector.

Last year, the Labour Court ordered that the Registrar of Labour Relations register the forum as a trade union, meaning it would be able to represent its members in disputes, wage negotiations, and in matters before the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA).

However, the Registrar has appealed this ruling.

The SWF is an off-shoot of the Casual Workers Advice Office (CWAO). Its application for formal recognition as a trade union was rejected by the Registrar. This led to the forum approaching the Johannesburg High Court and obtaining an order directing the Registrar to register it as a union within 14 days.

In that ruling, Judge Andre van Niekerk said that while the registrar had been correct that the Labour Relations Act treated unions equally, it was wrong in assuming that it necessarily followed that unions which did not adopt organisational structures which replicated those of traditional unions, could not register until there was a legislative amendment.

He said the SWF’s constitution provided for a position of a secretary and a chairperson for each meeting.

The judge said the SWF was entitled to be managed by a standing committee and that it did not have to employ officials. He said its constitution promoted greater accountability, responsibility and democracy through its flat, non-hierarchical structure.

However, the registrar said this ruling could not stand and is now seeking to overturn it.

The issues, the registrar submits in written argument, are whether the Labour Relations Act (LRA) can be interpreted to promote the right of trade unions to determine their own structures and organisation, whether the SWF’s constitution complies with the LRA, and whether SWF is a genuine trade union.

The registrar said the answer to all these questions was no.

Officials were employees of a trade union, as opposed to office bearers who get elected to their positions.

“We submit that a trade union cannot have a secretary or assistant secretary if they are not employed by the trade union in those capacities and a trade union cannot have office bearers not elected to those positions.

“In opposition to leave to appeal, the respondent (the SWF) contends that the work of the secretary general is performed by a collective (a standing committee). This is quite bizarre and not in line with the LRA which requires the office of a secretary. The respondent contends that the very same standing committee constitutes office bearers. This is even more astounding and confusing,” it submitted.

It was equally bizarre that the SFW contended that the registrar had presumed that all trade unions should adopt the same form and organisational structures as those developed by black South African trade unions which were established during the 1970s and 80s.

“The endorsement of these queer findings by the (labour) court by this (appeal) court will basically make the decision-making process in this office untenable. This office is in dire need of legal certainty.”

The registrar also questioned the independence of the SWF, saying it was inconceivable that it could survive should the CWAO shut down.

The registrar submitted that the appeal court should find that the SWF was not a genuine trade union. Alternatively, if it is found to be a genuine trade union, the labour court’s judgment and orders must be set aside on the basis that it was not ready to be registered as a trade union as it had failed to establish proper, accountable, offices.

The SWF, in its submissions, said there had been a tremendous increase in “non standard” employment, which coincided with a dramatic weakening of South Africa’s trade union movement.

Workers in this sector struggled to collectively bargain and were unlikely to access and enforce employment rights.

New worker organisations, such as the SWF, were needed and it was an example of a global trend.

“Its organisation practice emerged organically and addresses the twin challenges of impermanence and wage insecurity. A fluid but active membership is served by a standing committee, held close and tightly controlled by workers.

“In place of overarching policies and long-term campaigns, SWF derives its vitality and impetus from the immediate and often short-term struggles of its members. SWF’s unpaid leaders and volunteers perform work that is meaningful for them and they are motivated by the task itself, rather than by salary or access to entrenched power.”

The SWF said the question in the appeal was whether the LRA should be interpreted to deny this type of union the benefits of registration.

“The SWF sees the LRA differently [to the Registrar]. It sees it as enabling, not confining.”

The SWF said its structure was deliberately “flat”. Each meeting of members elected a chairperson and a secretary for the next meeting.

It had taken a deliberate decision not to employ officials; instead, all organisation work was done by members.

It said the central principle was the right of workers to freely associate and of trade unions to choose their own structures, rights protected by the Constitution, the LRA, and international law.

“It would be a bizarre interpretation of the LRA to prohibit workers from deciding to run a trade union themselves, without employing people to assist. Not only would that limit their associational rights, it would do so for no cognizable reason. There is no reason why employees would be better suited than members to run a trade union.”

The SWF said its relationship with the CWAO did not undermine its genuineness or independence.

It asked that the appeal be dismissed and the registrar be ordered to register it as a trade union within 14 days.