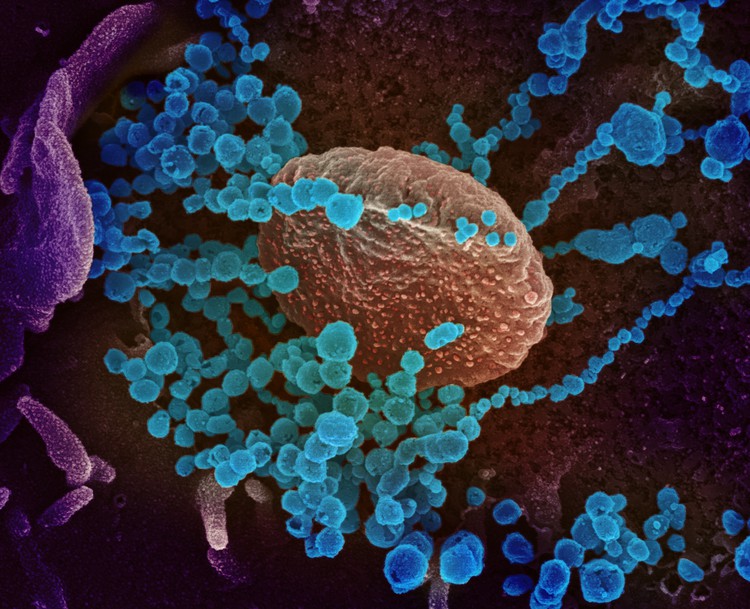

This scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19 (round blue objects), emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. SARS-CoV-2, also known as 2019-nCoV, is the virus that causes Covid-19. The virus shown was isolated from a patient in the U.S. Image by the US NIAID (CC BY 2.0)

25 March 2020

Are you wondering why you have to wait a few days for the results of the Covid-19 test? One reason is that laboratory technicians must take pains to avoid getting it wrong – what are called false negatives, and less often, false positives.

The other reason is that the techniques they use are done in a specialised laboratory, working with very small, precise quantities of what are known as reagents.

The first step is to take a swab from you as shown in this video from the New England Journal of Medicine (the world’s leading medical journal):

It may be a little uncomfortable, but grin and bear it; it’s for your own good.

You could also provide a sputum sample from your lower respiratory tract if you have a cough. A health worker will decide – based on your symptoms, and the guidelines issued by the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD), which route to take.

Lab technicians need the swab to check if you have the virus. They do this using a diagnostic test called a real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) test. To do a PCR diagnostic test, a laboratory technician isolates the genetic material of the virus from the sample you have provided. The PCR technique is well-developed and there is plenty of information about it online.

A virus is a small infectious agent that multiplies in living cells. Viruses contain nucleic acids, which are the building blocks of living organisms. DNA and RNA are the primary nucleic acids. Some viruses may contain single-stranded nucleic acids, others may contain double-stranded nucleic acids. A genome is the complete set of hereditary material in an organism. Some viruses have RNA genomes, while other viruses have DNA genomes. The genomes of some RNA viruses can be translated directly into viral proteins and they serve as a template for genome replication. They are described as positive-sense.

The coronavirus that emerged in late 2019 has a single-strand, positive-sense RNA genome.

PCR is a molecular biology tool that is used to amplify a gene segment from a very small sample of DNA. Many millions of copies are produced, which allows the gene sequence of interest to be studied further.

The first step involves transforming the RNA into DNA using an enzyme called reverse transcriptase. A small amount of DNA is amplified into larger quantities which will be more easily detected. In a standard PCR, the lab technician can only find out the result of the test once it is complete. In a real-time PCR, a camera or detector can “watch” as the reaction takes place and give real-time feedback on how the test is going.

The waiting period – the time you have to wait to get your results – may be due to a number of factors all of which contribute to the reliability of your test result. The crucial one is to reduce the risk of getting a false negative (when the PCR test says you don’t have the infection, but in fact you do).

According to the NICD, a false negative could occur when the specimen:

is of poor quality;

was collected late or very early in the illness; or

was not handled and shipped appropriately.

Technical reasons inherent in the test, for example virus mutation, may also lead to a false result.

False positives occur less often and may be the result of the slightest of contaminations in the testing process, among other factors.

The World Health Organisation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the NICD provide guidance for laboratory testing on their websites. But the Covid-19 virus is new, so testing protocols are being formulated and refined as new knowledge emerges.

At present, PCR tests can only be done in specialised laboratories. Even putting aside the time it takes to get the sample from the patient to the lab, the fastest available process takes at least four hours to get a result. This time includes the sample preparation and the actual analysis.

The backlog that is building up because of the increased demand for tests could mean the process will, in the short-term, probably become slower rather than faster.

Other, quicker, types of tests are needed.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has in the past few days approved a test developed by molecular diagnostics company Cepheid. It produces a machine called the Gene Xpert, the size of a desktop computer, which can be used in health facilities to do PCR tests for the new coronavirus.

But at this stage it is unclear how well the Cepheid test works, how quickly the company can produce the reagents needed for it, what these will cost and how quickly it can be rolled out across the world.

To permit the use of this test, the FDA, on 29 February, posted new rules allowing emergency use authorisations of coronavirus tests other than the ones made and distributed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The RT-PCR test is recommended by the World Health Organisation.

Another possible way for testing would be that recommended by David Ho, a viral epidemic expert, who suggested antibody testing in his interview with Caltech.

To fight viruses, your body will begin producing antibodies. An antibody is a protective protein produced by your immune system to help it fight this foreign substance. These are usually cheaper and quicker than PCR tests, and can be done at a clinic quickly, with a patient able to get his result before going home.

Reports are emerging of promising antibody tests, but at the time of publication none had been approved. Things are changing quickly, however. For example, on 18 March 2020, researchers posted a preprint on the Medriv website of a serology test which would identify the antibodies within three days of the onset of symptoms. A serology test is a blood test that looks for antibodies in your blood.

The researchers were clear that this was not a clinical trial, but the first development towards such a test.

On March 22, the WHO published it’s interim guidance for “Laboratory testing strategy recommendations for COVID-19”. It stipulated that “serological assays will play an important role in research and surveillance, but are not recommended for case detection at present”.

“The role of rapid disposable tests for antigen detection for COVID-19 needs to be evaluated and is not currently recommended for clinical diagnosis pending more evidence on test performance and operational utility.”

There is a lot more going on behind the scenes in the testing lab than most people realise. Entire teams are working to ensure your results are reliable.

The process, by its very nature, is painstaking and methodical.

But the good news is that throughout the world, scientists are working together, sharing knowledge that is being accrued by the day. They’re making tests that are quicker, and more reliable.

For informed information on how to proceed for testing, contact the National Institute for Communicable Diseases on its 24-hour toll-free number: 0800 029 999.