A Pollsmoor inmate employed as a nanny takes a baby for a walk. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

10 October 2016

Girelda* is playing with her eleven-month-old daughter on the bed they share in their home in Macassar. The pair have just been released on parole together. The child was born in Pollsmoor Prison while her mother served time for firearm possession. “Maybe she doesn’t need to know,” says Girelda. “But I know someone is going to tell her.”

Under South African law, children can stay with their mothers in prison until age two. Women who are pregnant when they enter Pollsmoor live in a separate unit until they give birth, at which point they move to the Baby Mother Unit (BMU) with their newborns. The mothers choose how long to keep their babies in jail based on their own preferences and the availability of other guardians for the child. Until 2008, children could live in jail until age five, but the legislation was changed when new research emerged on the damaging developmental effects of early childhood imprisonment.

When Girelda first thought she might be pregnant, she wrote a letter to a prison social worker to whom she felt close, Linda Loliwe. The social worker took Girelda to a clinic for the test and moved her to the pregnancy unit when it came out positive.

“I didn’t know how to feel,” said Girelda.

Loliwe, who works with pregnant women and mothers at Pollsmoor, thinks the first two years together are key for both mothers and babies in prison. “The first two years are when you form attachments, when you learn that ‘somebody loves me,’” she said. The babies can remember their mothers’ voices, she says. “They can remember their touch.”

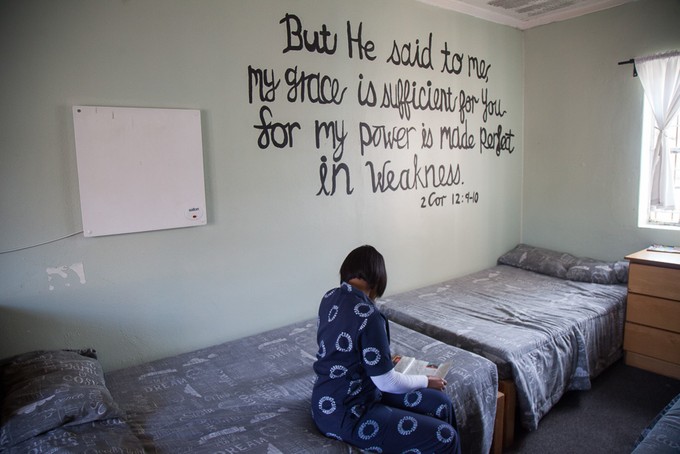

There are eight pregnant women and six new mothers under Loliwe’s care in the Pollsmoor Baby Mother Unit, which opened in 2011. The first of its kind in South Africa, it is a large one-storey house with a garden, picket fence, kitchen, and shared bedrooms. The creche next door has an indoor play area with toys and picture books. The BMU can provide lodging for eighteen mothers and their babies, and an offender can only stay there if her child also lives there.

Though the unit is just a few streets away from the maximum-security central Pollsmoor facility, it is surrounded by the houses of the prison staff, giving it the feeling of a suburban neighbourhood.

In good weather, prisoners employed as nannies wheel the infants in their strollers around the quiet streets of identical cinderblock homes. They can only walk for about ten minutes before running into a fence or a security guard separating the neighbourhood from the outside. Some of the wardens’ children play in the road, stopping to watch the nannies walk by in blue Pollsmoor uniforms. The women stop the strollers outside the metal gate topped by barbed wire and wait to be let back in by one of the BMU’s six female wardens.

Many mothers at Pollsmoor have other children outside of the prison system being raised by partners or relatives. For some offenders, “it’s the first time they’ve got to parent their children,” said Loliwe.

Girelda has an 11-year-old daughter who was brought up by her grandparents until Girelda was released from prison last month. When her older child was born, Girelda’s addictions made it difficult to be fully present as a mother, she said. As a teenager, she had fallen in with a rich crowd that liked to experiment with drugs. “Everybody used them, but most grew out of it.” Girelda struggled with drug dependency for years.

If her younger child had been born outside Pollsmoor, Girelda said she would have asked the grandparents to raise her. But “inside prison, it’s much different. It’s you alone.”

Lindiwe Jonas, director of the Female Centre at Pollsmoor and of the Baby Mother Unit, said the first two years spent together can deter mothers from committing new crimes after they are released. “It’s then that they realise, hey, I should be home with my children.”

Like other women in the pregnancy creche, Girelda gave birth at Mowbray Maternity Hospital.

She then returned to Pollsmoor to live in the Baby Mother Unit with her newborn daughter. A few weeks later, a Home Affairs truck came to the BMU to issue a birth certificate and register the child as a citizen.

Amahle**, who lived in the BMU with Girelda, has just sent her two-year-old son home to live with his grandmother. She said her transition from the Baby Mother Unit to central Pollsmoor, where she will finish her sentence, was “traumatic”.

“I’m still getting used to it.”

Amahle’s son was three months old when she was sentenced. For the first four months, she took care of him full-time. Amahle then received a position in the Pollsmoor textiles department, sewing uniforms for inmates and wardens. While she was at work during the day, Amahle’s son stayed with the nannies in the BMU creche.

“It’s not like you have a family environment,” said Amahle.

When she is released in November, Amahle wants to open her own sewing business and continue raising her son. “I’m hanging on to that,” she said.

Jessica**, Amahle’s roommate in the BMU, also sent her two-year-old son home last month to live with his grandmother. “Sometimes I was thinking I’m selfish to keep him here,” she said, but “that’s what keeps me going - the memories. My hopes are to go outside and still have that bond that we had inside.”

Stephanie van Wyk, director of the halfway home Beauty for Ashes, has been running skills workshops and religious programmes for women in Pollsmoor since 1997. She said the conditions for mothers and babies at the prison had improved significantly throughout her career.

Until 2011, babies at Pollsmoor, like in other South African prisons, lived in the cells with their mothers. Their only exposure to the outdoors was a cement courtyard, and the infants were surrounded by “the slamming of gates, people swearing and fighting,” said van Wyk. The new unit is so different that it often inspires animosity between women who must stay in the main facility and those living at the BMU, she said.

Kathy*, the house parent at Beauty for Ashes and a former Pollsmoor inmate, said the unit was “lovely” by prison standards. The unit has hot water while the rest of Pollsmoor does not. The BMU kitchen serves fresh fruit and vegetables nearly every day.

It’s a far cry from facilities elsewhere in South Africa, said Stacey Adams, board member of the advocacy group Babies Behind Bars. Her organisation, which works primarily in Gauteng, has found there is little intellectual stimulation for the babies in prison and problems with medical care. Babies in Gauteng often do not receive vaccinations because the prison clinics are out of stock. It takes one to two weeks for a mother to request that her child be taken to a doctor outside.

“The women are prisoners at the end of the day, and they don’t get special benefits,” said Adams. “And the babies suffer.”

Girelda was one of the “lucky” ones, said the BMU social worker, because mother and child were released together to a safe home with supportive maternal grandparents. In most cases at the Baby Mother Unit, the mother’s sentence exceeds two years, and social workers must find alternative guardians for the infant until her release.

Loliwe said she begins this placement process as early as possible. If the mother has a relative who could raise the child — usually a grandparent — Loliwe asks the office of the Department of Social Development (DSD) in the mother’s community to perform a background check on the potential guardian. Officials meet the relative, reviews his or her employment, criminal, and medical history, visits the home where the child might stay, and reports back to Loliwe. If both social work teams agree that the guardian is suitable, they begin a series of visits so that the infant can get used to the new family.

If the social workers consider the guardian unsuitable, they explore options for foster care or, as a last resort, children’s homes. In the three years that Loliwe has been working for the Baby Mother Unit, two babies have been fostered and one infant placed in a children’s home.

Almost all guardians of babies who lived in the BMU are eligible for the child support grant of R350 per month or the foster grant of R890 per month if they legally foster the child. Loliwe begins the grant application process while the baby is still at Pollsmoor, but guardians only receive the money once the child has entered into their care.

Monique is another of the “lucky” ones at Pollsmoor. She and her one-year-old daughter have just been released from the BMU together. Monique was arrested last year for robbery, which she says was motivated by drug dependency. She was let out on parole, but she violated the conditions of the parole and re-entered prison. While on parole she fell pregnant.

Monique stayed in the pregnancy unit and moved to the BMU with her daughter once she was born. “I wouldn’t mind going back there,” Monique said. “There isn’t anything for me on the outside.”

The newborn was Monique’s second child, and, she said, “I did not give [my older daughter] the love I’m giving this one.”

Monique and both her daughters now live with the children’s paternal grandparents in Macassar. Monique’s boyfriend, the father of her two children, must serve 18 more months in prison and will go to court soon for a potentially longer sentence. Monique relies on the child support grants — R700 a month for both children — while she looks for work.

She says the job search has been challenging, though, because many employers will not hire someone with a criminal record. Transport to the city centre to look for work is expensive. She plans to ask her boyfriend’s parents for a loan for next month to cover extra food and nappies for the one-year-old.

“It’s almost like God put me [in prison] for a reason. He knew I had no support.”

Crying while stroking her baby daughter’s hair, Monique said, “I just want her to have the education I didn’t have.”

Beauty for Ashes is one of the few programmes in Cape Town that assists women leaving prison. Most of the time, women have to stay with relatives and rely on the social grant system until they find employment, said Loliwe.

Beauty for Ashes resident Carol* is serving her parole time at the center while her three sons live with their grandmother. None of the boys lived with her in Pollsmoor, but they visit her on weekends.

Women getting out prison “do have places to go, but they are not the right places,” she said. She and many of her peers coming out of Pollsmoor were faced with the prospect of returning to abusive relationships and violent neighborhoods, where it was tempting to fall back into drug addiction.

For women leaving prison, Carol said, “my advice is, don’t go back where you came from.”

* only first name used to protect identity and criminal record

** names have been changed