Fishers at Struisbaai.

24 February 2016

It has been a long road for small-scale fishers in their pursuit of increased rights and recognition, with bureaucratic processes halting the implementation of the small-scale fisheries policy.

That policy aims to ensure that small-scale fishers have both rights and equal access to marine resources. The policy is set to be implemented soon and a new mobile app, called Abalobi, is using this new policy environment to record fishing activity and connect fishers, scientists and fishery

In 2007 small-scale fishers won a landmark case in the equality court where the State was compelled to finalise a policy for the small-scale fisheries. The Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries also acknowledged that small-scale fishers had been disadvantaged by previous decisions that had allocated marine resources mainly for commercial and recreational purposes.

In 2012 the policy was finalised but was unable to be implemented as the Marine Living Resources Act Amendment Bill needed to be signed off first. This took another two years. Small-scale fishing regulations then needed to be written up, which have now been approved, paving the way for the amended bill to be finally be promulgated, following which the regulations will be published.

A central tenet of the policy is enabling the co-management of the fisheries sector. The Abalobi team, which is a partnership between the University of Cape Town, The Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries and small scale fishers themselves, believes that one way that this can be done is through fishers collecting data and sharing it will other fishers, scientists and fishery management.

Abalobi’s director and UCT project leader Dr Serge Raemaekers says that the app is simply a “conduit” through which “local beliefs, local knowledge and local images” of small-scale fishers can be included in fishing management decisions.

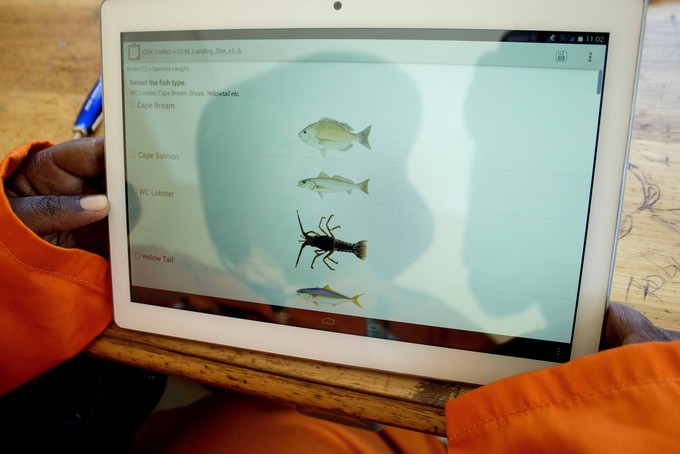

In the app, fishers can record all the information related to their catch such as the weight of the catch, where it was caught, what species it is, the sea conditions and their income and expenses. Eventually the app will also have a communication and safety at sea component and will also be able to connect fishers to suppliers.

The small fishing village of Struisbaai is one of the five areas where Abalobi is being piloted. Struisbaai is near Cape Agulhas, where the Indian and Atlantic Oceans meet, with the harbour being the pivotal point around which the village operates.

Sea and weather conditions determine whether fishers are able to go out to sea and when GroundUp visited the Struisbaai the conditions were poor, meaning that there were only a few boats out at sea. At midday the boats — many looking in need of repair — began to come into shore and offload their catch: yellowfin tuna, stumpnose and some small sharks were offloaded from the boats.

Niklaas Joorst, the skipper of one of the boats, is one of the five fishers in Struisbaai involved in the pilot of Abalobi. He believes that the app “will help a lot of people” if all fishers in Sruisbaai could use it, with one of the major benefits being able to set prices amongst the fishers so that they have increased bargaining power. In the bigger picture this would also mean that the information that fisheries management is gets is accurate, up-to-date and reflective of all fishers in the sea.

Joorst puts all his data into the app when he comes back from sea, saying that it has helped him a lot as he is able to go back over his data every month – looking at income, expenses and his catch.

The Abalobi system would make the notorious “blue books” obsolete. The “blue books” are where fishers currently record data pertaining to their catch – a process that is time consuming and often does not result in adequate feedback to the fishers themselves.

“The Abalobi is a much better system [than the blue books],” says Joorst.

This is something that Josias Marthinus, a catch data monitor in Struisbaai agrees with. Marthinus’s job is to record data from each fisher’s catch, such as the weight of the catch and the species, which is then given to the department

Currently he has to write everything out by hand and the data is only collected once a month.

“We sit with the data the whole month,” he says, “I use many [pieces of] paper per boat.” Marthinus has now been equipped with a tablet loaded with the Abalobi app, meaning that with a couple of clicks he is able to fill in the data for each fisher’s catch.

Marthinus says that the data captured on the app can help fishers secure bank loans to fix their boats and can also aid in paying taxes as they now have detailed data on their income and expenses.

The data from various fishers using the app can also be combined to create a picture of the Struisbaai fishery, something that Stuart du Plessis, the Struisbaai project manager and implementation leader, says never happened before.

“[Before the app] When fishers sent information [about their catch] away, it was never returned. They will never see [its effect],” he says.

Du Plessis says that fishers are given things such as quotas and a total allowable catch but that the fishers do not know where the data for these restrictions came from or how the final allowances were worked out.

“It is of vital importance that these communication groups come together and support and increase the trust amongst them,” he said.

Mistrust between small-scale fishers, scientists and fisheries management is a perennial problem say both Raemaekers and du Plessis.

Raemaekers explains that scientists often believe that fishers are going to under- or even over-report, depending on circumstances, because they will benefit more from doing this. “The current setup doesn’t work too well. We need to turn it around – looking at ownership, looking at co-producing, looking at partnerships,” he said.

The policy provides the framework for this, but the app is a method by which it can actually be facilitated.

Du Plessis believes that the app is “brilliant” and “is definitely going to revolutionise the fishing industry”.

While the app is still in its pilot stage, the team is hoping it will soon be available for download so that every small-scale fisher can use it. As for its future, Raemaekers insists that the fishers will be the ones who dictate the direction it takes.