Woodstock Hospital is one of 13 sites set aside by the City of Cape Town for developing housing for low-income families. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

9 November 2017

There has been much celebration about the City of Cape Town’s announcement in September that social and affordable housing will be developed close to the city centre. And rightly so. No more “emergency” housing in Blikkiesdorp and Wolwerivier!

At a housing briefing for developers at the Civic Centre on 24 October, the City announced that it would consider proposals with minimum social housing units at these sites: Fruit & Veg City, 50 units (ideally integrating the existing community garden); New Market Street, 300 units; Pickwick Road, 600 units; Woodstock Hospital, 700 units; Woodstock Park, 200 units (ideally with public open space).

Mayoral committee member for transport and urban development Brett Herron says the new housing policy wants to address ‘the spatial legacy of apartheid’ and that it identified these sites in the ‘pursuit of spatial transformation’. This is what Ndifuna Ukwazi and other organisations and individuals advocating for social justice have been asking for all along.

But what happens when we look beyond the buzzwords and at some data?

With the Bo-Kaap, Woodstock and Salt River are the most integrated spaces in the greater city centre, partly because resistance to the bulldozing of District Six prompted the apartheid government to stop removing the original residents from the area.

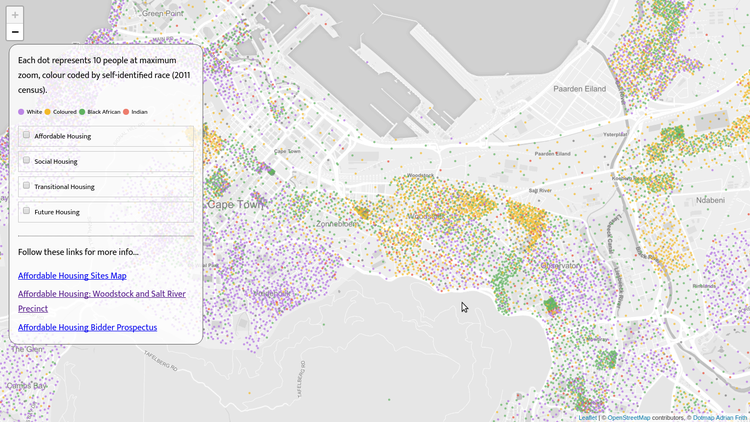

Since the end of apartheid, the affordable area has attracted black, white and coloured households. This has created a diversity seen nowhere else in Cape Town, as recorded on this map of the most recent census data. The diversity includes race, religion and income – according to the City’s numbers, 32% of households in Woodstock and Salt River already fall into the income bracket considered for social housing, and a further 30% of households are too poor even for that (they earn between 0 and R3,500 a month).

This raises the questions: does developing social housing in Woodstock and Salt River address the spatial legacy of apartheid? And how is the City addressing the most glaring apartheid spatial legacies in the areas which are dominated by purple dots on the map: the mostly “whites only” areas?

Brett Herron and the City are dodging this question and no-one has insisted on answers. Ndifuna Ukwazi has questioned the Province on the failure to build affordable housing in Sea Point, but when it comes to Cape Town, it seems the City’s slogan “Where people live matters” has won them over. Even the GroundUp editors only ask coyly: “Dare we hope for even braver policy decisions from all levels of government, such as affordable housing in the richer parts of the city … like Sea Point?”

The plan for the Woodstock Hospital site and what the City calls the Hospital Park across the road is the construction of at least 900 social housing units. How many units in total (including “non-affordable” ones) is the development likely to entail? Is the City really planning to put another small town into just that area?

Plans to use the Woodstock Hospital Park – the only green space in that part of Woodstock – for affordable housing are not new. Previous City governments made similar moves, which the residents of Woodstock have resisted, and instead pushed to improve the space so that it’s now used as an orphanage/creche, a playground and dog-walking space with a dog watering spot and a sports field where local schools hold events. The City says the plan is to keep an ‘interactive public space’ there. How will that fit with at least 200 residential units?

The 700+ housing units on the Woodstock Hospital site will be be squeezed on a property the size of not even 2.5 soccer fields. For comparison: the existing Steenvilla development has 700 units on a property the size of 9 soccer fields.

In its development prospectus, the City states that Woodstock and Salt River currently have 5,187 households. Between private developers and units developed by social housing partners, the City is planning for a minimum of 2,090 affordable housing residential units – that’s a 40% increase in households in an already dense area. That figure does not include any of the “mixed” higher income and commercial units. If these are included the increase in households could be closer to 50%.

What the neighbourhood thinks about the scale of the developments or all the particular sites combined doesn’t matter to the City. There is no public participation process regarding the development. “We’re not debating if the projects should happen, or where they should happen. That’s been decided already, and we need to move forward,” says Brett Herron, as the City moves ahead apace with development proposal deadlines in February 2018.

In the housing developers’ briefing, the City made it clear that the decision has been taken and will not be changed by facts – or laws. Bulk restrictions? Height restrictions? Change of usage zoning? The City said a plan would be made if the chosen developments do need exemptions, suggesting any possible objections from neighbouring residents will be ignored. This would hardly be the first development that the City is willing to push through at any cost and against strong community resistance: the 18-story building at the edge of the Bo-Kaap has been approved, against heritage recommendations by all relevant departments in the City, overruling more than 1,000 objections.

Instead of meaningful public participation, the City will have a “public vote” that will give the winning development proposal five points in the evaluation. The five points equate to a 5% influence on the decision.

Meanwhile, the Woodstock Urban Development Zone, where the City offers tax incentives to developers below Main (Victoria) Road, has led to many Woodstock residents getting evicted to make space for large property developments. Evictions below the Main Road, social housing above the Main Road?

While there is a pressing need for affordable housing, it is not clear why the City does not go ahead with some of the developments in Woodstock and Salt River and check to see if this works before going ahead with the others. Why the all-at-once approach? Are Woodstock and Salt River merely low hanging fruit where the City doesn’t expect pushback?

Many residents of the area feel strongly about social justice issues and would not want to be seen to be objecting to affordable housing opportunities even if the process, scale, concentration and the all-at-once timing of the projects in their neighbourhood seem flawed.

Even if there is pushback from the residents, the City’s sledgehammer approach has left it plenty of room to appear to back down and offer a compromise – so we might end up with “only” 50 units on the Hospital Park site, or none on the Hospital Park site, but more than units on the Hospital site – and we will never figure out that we have been had.

Worse: while celebrating a ‘change’ in policy, we are letting the DA get away with its strategy of “land for profit” rather than “land for people”.

This article does not necessarily reflect the views of GroundUp.